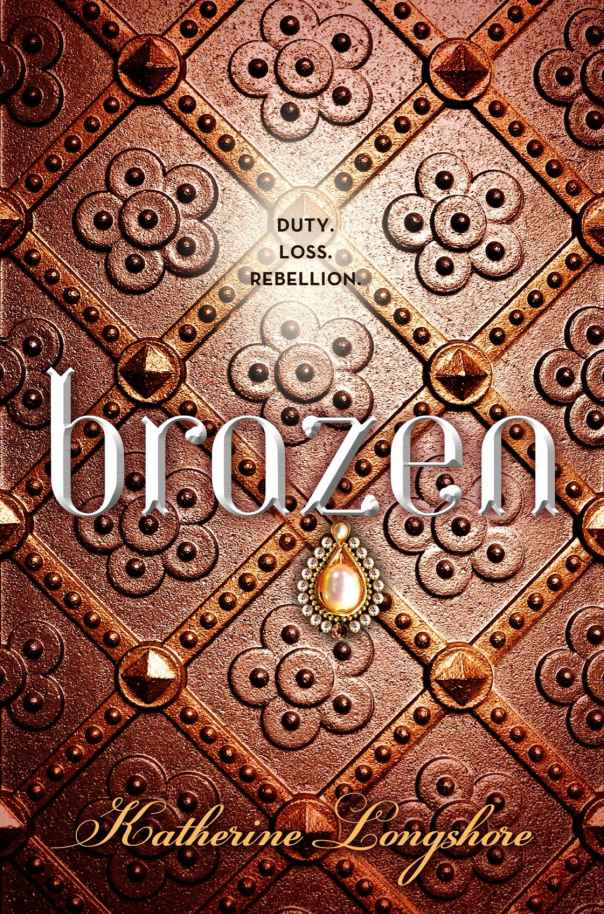

Brazen

Authors: Katherine Longshore

ALSO BY KATHERINE LONGSHORE

Gilt

Tarnish

VIKING

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) LLC

375 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10014

USA * Canada * UK * Ireland * Australia

New Zealand * India * South Africa * China

A Penguin Random House Company

First published in the United States of America by Viking, an imprint of Penguin Group (USA) LLC, 2014

Copyright © 2014 by Katherine Longshore

Penguin supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part of it in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin to continue to publish books for every reader.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA

Longshore, Katherine.

Brazen / by Katherine Longshore.

Summary: Mary Howard, always in the shadow of her powerful family, marries Henry VIII’s illegitimate son, Fitz, but their carefree life unravels as Queen Anne Boleyn falls out of favor and they are implicated in horrible rumors.

ISBN: 978-0-698-14491-0

1. Richmond and Somerset, Mary Fitzroy, Duchess of, 1519–1557—Juvenile fiction. 2. Great Britain—History—Henry VIII, 1509–1547—Juvenile fiction. [1. Howard, Mary, Lady, 1519–1557— Fiction. 2. Great Britain—History—Henry VIII, 1509–1547—Fiction. 3. Kings, queens, rulers, etc.— Fiction. 4. Courts and courtiers—Fiction.] I. Title.

PZ7.L864Br 2014 [Fic]—dc23 2013026557

Version_1

M

ARRIAGE

IS

A

WORD

THAT

TASTES

LIKE

METAL

—

THE

STEEL

OF

armor, the gold of commerce, the iron bite of blood and prison bars.

But also bronze. A bell that rings clear and true and joyously. Like hope.

As my father guides me through the palace rooms to the chapel, I don’t know which way the door to my cell will swing. It could ring loud, metal to metal, locking me into a life I never asked for. Or it could open wide, hinges creaking, into a life I never imagined.

I concentrate very hard on not tripping over my own train as we turn the final corner and proceed through the chapel doors. I will never hear the end of it from my mother if I blunder.

Henry FitzRoy is already there. Watching me.

My family has known him for years. When he was a child, Father helped organize his household, his tutors, his finances, his friends. My brother, Hal, was sent to Windsor to be his playmate.

But I don’t know him. I don’t know who he’s become. All I remember is a little boy with golden-red hair and eyebrows that seemed to soar right off the top of his forehead. A little boy with no chin and an air of superiority.

It appears I’m marrying someone quite a bit more attractive.

His eyebrows still arc high into the fringe of hair ready to fall into his eyes at any moment. Eyes the color of a clear winter dawn. His nose is perhaps a little too big for the mouth below it, the full lower lip complementing the now well-defined chin.

The mouth tips into a smile. Of relief? Or of expectation?

As I watch, unmoving, one eyebrow curves even higher.

A question.

An invitation.

A challenge.

Father walks me to the altar. The shallow, barrel-vaulted ceiling looms heavy overhead. The magnificent stained-glass window in front of me filters the light of the wintry sky through depictions of the king and his first queen, Katherine. To either side of me stand witnesses dressed in gaudy blue and green and crimson. My eyes never leave the boy in front of me.

Father squeezes my arm and whispers, “Make me proud.”

I say the only thing I can.

“I will.”

We turn to face the priest and Father puts my hand in Henry FitzRoy’s. His palm is rough beneath my fingers; his sleeve tickles my wrist. He is taller than I am, his presence beside me solid.

His breath comes easily, while mine is trammeled in my throat from fear.

And something else.

I search my heart. It can’t be love. I don’t even know this boy. And it’s not lust, despite his good looks. Besides, I don’t really know what either of those is supposed to feel like.

I glance at my father out of the corner of my eye. See the glitter in his as he stares straight ahead, lips pressed against his teeth to suppress a grin. I recognize what I see there reflected in me.

Triumph.

A Howard marrying the son of the king.

“I take thee, Mary, to be my wedded wife.”

FitzRoy sounds so assured, saying those words. As though making that promise is as easy as stepping into a role in a masque.

Which is really what we’re doing. He wears the mask of husband. I represent wife. We will perform this showy little dance for the pleasure of king and courtiers, fathers and family.

Then we will exit the stage and go our separate ways.

I risk another glance from below my lashes.

FitzRoy catches me looking at him, and I turn quickly back to the priest. Watch the watery blue eyes floating in a sea of creases. Watch his mouth move, the words like vapors.

And then it’s my turn.

“I take thee, Henry . . .”

I stumble once.

Till death us depart

. Death is so far away. We’re only fourteen—

till death

is a long promise. It’s a long time to be imprisoned by our

parents’

actions and not our own.

A breath of cold air brings gooseflesh to my arms and neck.

The priest takes my hand, his skin cool and papery, sliding like the discarded shell of a beetle. He places my right hand in that of my husband and binds us together with a white ribbon. Raises his hands in benediction.

Then it’s over. All hands are dropped. FitzRoy and I turn together to face our collective families. My parents stand to my right, not touching, not speaking—in fact, each pretending the other doesn’t exist. But together. In the same room. A miracle if there ever was one.

And suddenly, in the doorway, dressed in crimson and cloth of gold and shining like a newly fat sun, there is my husband’s father. The king. And his wife, my cousin, Anne Boleyn. They must have been watching from the privy balcony, hidden above us.

The king calls me daughter and kisses me on the mouth. I fight the urge to wipe his spittle off as he claps his son on the shoulder.

“The bride and groom!” he shouts.

I look at my new husband again and find him already watching me. Bride and groom. Husband and wife. Strangers. I don’t even know what to call him. Your Grace? Henry? Husband?

“Fitz!” My brother rescues me with a shout that rings off the windows. Hal kneels before the king and queen, then stands to throw his arms around my husband and pummels him.

“A married man, Fitz!” he shouts again, his joy contagious.

“Same as you, Hal.”

My brother laughs, but with a little less mirth than before. I’m not sure he likes his wife.

Fear clutches at me and I look down at my hands.

“We’re related now,” Hal says, sounding overly gracious. “You can call me Surrey.”

Mother and Father never called Hal anything but Surrey—making sure the earldom stuck for good. When the two Henrys met as children, they decided that calling each other by their first names was too confusing. And that Richmond and Surrey were too formal. Henry FitzRoy gave Hal his nickname. So Hal dubbed him Fitz in return.

Fitz laughs and wraps his arm around Hal’s neck, nearly throwing him to the floor. The rest of the congregation charges forward, uplifting them both, so close there is no space between the bodies and I cannot breathe, my vision limited to the bright chevrons of green and blue on the sleeve in front of me.

I slide out between them all and swallow air like a landed fish.

“You blundered.” My mother has dressed in black for the happy occasion, the velvet of her gown sucking the light from the chapel windows while the gold braid of her hood reflects it. Like a halo. The darkness of her eyes negating any semblance of divinity.

I try to still the trembling of my limbs.

“And slouched.”

I stand up straight. Shoulders back. Neck elongated.

If my life is a prison, my mother is my jailer. Her words turn the locks of fourteen years of daughterhood, keeping them tightly closed.

The word

daughter

tastes of bitterness. At least in my mother’s mouth, it does.

The group beside us bursts into raucous laughter, but we are in our own little circle of misery. My mother’s mouth turns down, the lines around it sharply defined.

I hold my breath. I know what that face precedes.

“A feast!” The king’s voice breaks us apart and I take advantage of it to move closer to my father. He always takes my side.

That is why I will always take his. Even when it’s the wrong one.

“And a celebration,” Father says, his narrow face animated, “of the joining of families.”

The king takes Queen Anne’s arm and strides out the door into the cloister. My mother steps up behind them. She is the Duchess of Norfolk—second only to the king’s kin and protective of her own precedence. She hesitates when my father doesn’t move to join her. Glares her disapproval.

She opens her mouth and I cringe, waiting for the vitriol sure to spill forth.

“Your Grace.” My new husband steps forward, nods his head in a quick bow.

Everyone stops—even the king and queen. They turn, eyeing the flow of people snagged in the doorway behind my mother.

“Your Grace,” Fitz says again, quietly. Intimately. Yet his voice, rich and luxurious as velvet, deep and smooth, carries throughout the silent church. “Mother.” He smiles, almost shyly. Engaging and embarrassed.

She hesitates.

And then she smiles back. I suppress a gasp.

“I feel I must remind you”—he pauses and leans closer to her, his tall, supple frame curling slightly over her small, inflexible form—“I am the Duke of Richmond and Somerset.”

Mother goes pale.

“Your daughter is now my wife.”

He cuts a quick sideways glance and a heart-stopping smile my way.

“She is my duchess.”

His.

His wife. His duchess. His prisoner, if he so chooses.

For the first time, I really look at him. Try to see the whole and not just the parts. The eyes, brows, nose, mouth, chin encompassed by a face still round with a boyhood completely at odds with his bold self-confidence.

He raises an eyebrow into the flop of hair.

Definitely an invitation.

“She should have precedence.” He unfurls his arm and holds out his hand. To me.

I hesitate. I know that if I step in front of my mother, she will never forgive me. But I do it anyway, my train whispering behind me. Or perhaps it is the hiss of Mother’s breath as she sucks it in through her teeth. I take Fitz’s hand, warm and tight and . . . comforting.

I allow my husband to escort me to the chapel door—behind no one but the king and queen.

In the distance—beyond the great hall—I hear a bell ringing.