Broadmoor Revealed: Victorian Crime and the Lunatic Asylum

Read Broadmoor Revealed: Victorian Crime and the Lunatic Asylum Online

Authors: Mark Stevens

Tags: #murder, #true crime, #mental illness, #prison, #hospital, #escape, #poison, #queen victoria, #criminally insane, #lunacy

Revealed:

the Lunatic Asylum

Edition

2011

This edition

was published electronically in summer 2011. Most of the stories

can also be read on the Berkshire Record Office website,

www.berkshirerecordoffice.org.uk/albums/broadmoor

.

Comments and corrections are welcome: visit the Berkshire Record

Office website and click on ‘Contact Us’.

Mark

Stevens

c/o The

Berkshire Record Office

9 Coley

Avenue

Reading

RG1 6AF

Mark Stevens

has asserted his moral right to be identified as the author of this

work in accordance with the UK Copyright Designs and Patents Act

1988.

Smashwords

Licence statement:

Thank you for

downloading this free ebook. Although it is a free book, it remains

the copyrighted property of the author, and may not be reproduced,

copied or distributed for commercial or non-commercial purposes.

Thank you for your support.

Constructed in

the Smashwords Meatgrinder.

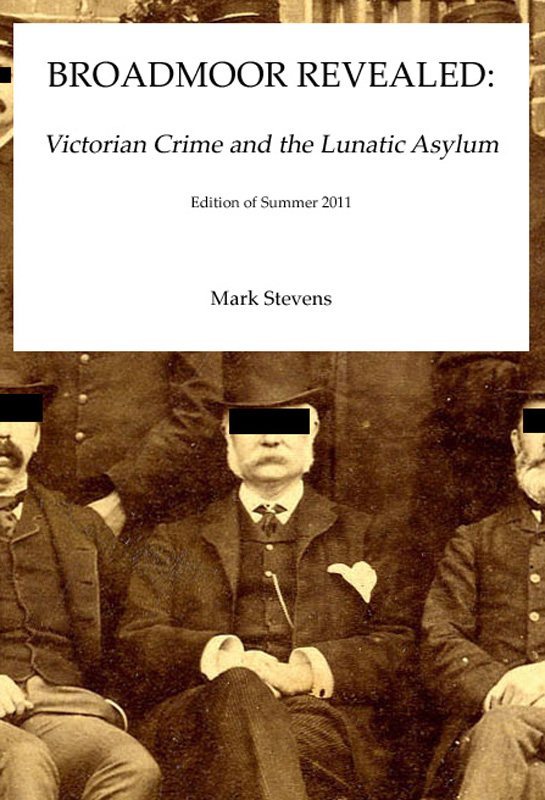

Front and rear

covers show a photograph of the male staff at Broadmoor, taken to

commemorate the retirement of Dr William Orange, 1886. Orange is in

the top hat in the centre of the front cover, flanked by his

medical staff. Berkshire Record Office reference D/H14/B6/1.

Broadmoor Hospital: By Way

of Introduction

Edward Oxford:

Shooting at Royalty

William Chester

Minor: Man of Words and Letters

Christiana

Edmunds: The Venus of Broadmoor

This short

collection of stories grew from work to advertise the many personal

tales contained in the archive of Broadmoor Hospital. When, in

November 2008, the Berkshire Record Office made the archive

available for research, it was the first time that the general

public could access the historic collections of what was England’s

first Criminal Lunatic Asylum. As the person responsible for

promoting use of the archive, it fell to me to piece together some

stories of the more well-known patients, with the idea that this

would raise awareness of the fact that the archive existed, and

give researchers an idea of what they could discover about the

people who spent time in the Hospital.

This was and

is not always a straightforward task. As you might expect, a lot of

restrictions for access remain on the archive. Particularly,

patients’ medical records are closed for a considerable time. This

meant that any publicity had to focus on the Victorian period, and

so I began to put together brief biographies of those nineteenth

century patients who are already part of public consciousness.

Their stories are here: Edward Oxford, Richard Dadd, William

Chester Minor and Christiana Edmunds.

However, those

are only four patients out of over two thousand admitted before

1901. They are also four patients about whom others have written,

and about whom others are more qualified than me to write. So for

me, the more interesting thing became how to tell some stories that

were not well-known. There is no shortage of such material. You

could choose virtually any patient and manage to bring something

new to our understanding both of Victorian England, and also about

the care and management of the mentally ill.

I chose a

couple of things to write about as part of the Berkshire Record

Office publicity. Firstly, I felt that the women of Broadmoor

needed to be heard, and that Christiana Edmunds was too unusual a

case to be representative of that group. On the other hand, a

representative female case would have to be a child murderer, and

this would potentially lack the redemptive element of the male

stories of Oxford, Dadd and Minor, who were all remembered for

achieving something despite their illnesses. Being a man, and

therefore impressed with all things maternal, I thought that a

great achievement of some female patients had been to give birth

while they were in Broadmoor, so I decided that I could balance my

infanticide narrative by writing about the babies who came into the

world through the Asylum, as well as those who had left it.

Secondly, I considered that I should not shy away from the

non-medical aim of the Asylum, that of being a place of public

protection. Rather than dwell on tales of violence and rage, I

thought that a more entertaining way to highlight this would be

through the concept of escapes. By writing about those that were

successful or otherwise, I thought that I might also be able to

dispel some of the preconceptions there might be about the dangers

of an escaped lunatic.

So that this

book has been put together from these individual pieces. As such,

it is a tasting rather than a full bottle. In the longer term, it

is my intention to complete another book about Victorian Broadmoor,

which is planned as something different from a narrative history.

The reaction to this short collection will give me an idea whether

such a pursuit is worthwhile. There is so much I could tell you

about the place: but, for now, perhaps I had best let you read

on.

Mark

Stevens

Reading,

Berkshire

2011

Hospital:

By Way of

Introduction

On 27th May

1863, three coaches pulled up at the gates of a recently-built

national institution, which had been set amongst the tall, dense

pines of Bracknell Forest. Inside these three coaches were eight

women and their escorts from Bethlem Hospital in London, the

ancient hospital for the treatment of the insane. It was now early

afternoon, and that morning, the little party had left the Bethlem

buildings in Southwark, boarded a train at Waterloo and been taken

by steam through the capital’s suburbs and out to the little market

town of Wokingham in Berkshire. Their destination was Broadmoor,

England’s first Criminal Lunatic Asylum.

At half past

twelve, they had alighted from the train at Wokingham’s simple

railway station and found the three coaches waiting for them: a

larger one, grandly-titled the Broadmoor Omnibus, together with two

smaller vehicles. These carriages would take them on the last leg

of their journey. The eight women and their accompanying paperwork

were loaded into the seats, before the steps were removed and the

horses started. Then the wheels of the coaches spun down winding

earthy lanes and finally up a gentle incline as the passengers were

driven the five miles to Crowthorne. Broadmoor’s first patients had

arrived.

Who were these

women? As befitted a group thrown together without friendship, they

had different backgrounds. One was a petty thief, for example,

while another had stabbed her husband when they were out poaching.

Then there were the other six, who had all shared a single life

event. They had killed or wounded their own children: either

strangling them, drowning them, or cutting their throats with a

razor.

It was one of

this last group who was the first patient to be listed in the new

Asylum’s admissions register. Her name was Mary Ann Parr. She was

about thirty-five years of age, and a labourer from Nottingham. She

had lived in poverty all her life, almost certainly suffered from

congenital syphilis, and had what we would now call learning

disabilities. Mary might have been just another member of the

industrial poor, except that when she was twenty-five years old,

she had given birth to an illegitimate child and then suffocated it

against her breast. She had been convicted of murder and sentenced

to death, but her sentence was commuted first to transportation for

life, and then, after a medical examination, to treatment instead

in Bethlem.

When Mary Ann

Parr arrived at Broadmoor, as with every patient who would come

after her, her details were first recorded from the forms that had

accompanied her, and then she underwent a medical examination and

an interview with one of the doctors. All the while, notes were

taken, and these notes were then written up into a large case book,

and added to over the years. This is an extract from the notes made

about Mary Ann Parr on admission: ‘A woman of weak intellect,

complains of pains in the forehead, short stature, cataract of the

left and right eyes – can see a little with the left eye only.

Teeth irregular and notched…Of very irritable temper.’

Mary Ann Parr

and the other new patients were given the best treatment that was

available at the time. This was rather different to how we might

understand mental health treatment today. There were no drug

therapies available for the mentally ill during Victorian times,

nor psychiatric analysis. Instead, Her Majesty’s lunatics were

subject to a regime known as ‘moral treatment’. This was a

recognisable Victorian concept. Mary was given a regular daily

routine of exercise and occupation (which for her meant working in

the laundry); regular meals of fairly bland food; and plenty of

fresh air. She was also given relief from her poor and harsh

surroundings. Her quality of life was probably significantly better

than that she had enjoyed outside: she had a roof over her head,

and she did not have to worry about food or money. This removal of

a patient from their usual society was another aspect of Victorian

treatment. By giving a patient refuge in the Asylum, the Victorians

believed they would be able to neuter the immediate causes of

insanity in their day-to-day life, leading to beneficial results.

It was a recognition that community living could create problems as

well as solutions.

Mary Ann Parr

was a reasonably typical recipient of this treatment regime, in

that she experienced it for the next thirty-seven years, until she

died in 1900, aged seventy-one, from kidney disease. Many patients

spent decades on site, and became institutionalised in the process.

It was by no means a given, though, that this outcome would

prevail. The discharge rate on the male side was around one in ten,

and even greater on the female side, with slightly more than one in

three patients being discharged. This was, in part, due to the

patient make up. While the ‘pleasure’ men and women’s fate lay

ultimately with the Home Secretary of the day, a significant

proportion of patients arrived from the prison system with a fixed

sentence. Once that sentence was complete, they were usually

discharged to a local asylum for care.

***

The fact of

Broadmoor’s opening does not explain the fact of Broadmoor’s

creation. Every story has a beginning, and in Broadmoor’s case this

is usually traced back to a spring day in 1800. It was on the

evening of 15th May that year that King George III chose to attend

the Theatre Royal in Drury Lane, London, only to feel the whistle

of two shots pass near him before he had taken his seat in the

royal box.

The assailant

was a member of the audience. James Hadfield was a young father

from London convinced that he needed to secure his own death at the

hands of the state. By suffering the same fate as Christ, Hadfield

believed that his personal sacrifice would benefit all mankind by

ushering in the Second Coming, and the Day of Judgement. This was a

fact that would emerge later. For now, Hadfield was restrained in

the orchestra pit of the Theatre as pandemonium raged around

him.