Brother Termite

Authors: Patricia Anthony

THE BULLETPROOF GLASS

in the Oval Office windows cast a gloom over the day, the sort of greenish pall associated with bad storms. Appropriate clouds rose from the Ellipse, pluming easterly in the late autumn breeze. On E Street a string-straight line of troops prepared to advance. The White House chief of staff knew that had the French doors been open he would be hearing the chuck-chuck of the tear-gas guns, the rattle of the Uzis’ rubber bullets, and the screams.

Eisenhower had warned him this would happen.

Doggedly he swiveled away from the riot, his leather chair squeaking, to face the mantelpiece and the portrait of Millard Fillmore that hung above it.

The door behind him opened with a click. His secretary announced, “Sir. The NSC’s finally arrived through the Treasury Building tunnel. They’re waiting for you.”

Wearily he rested his chin on his hand. The President, in one of his frequent tutorials on politics, had assured his chief of staff that governments existed only by the apathy of the governed. The people outside, with their placards and Molotov cocktails, seemed troublesomely unapathetic.

With a surge of will he pictured himself as a pool. The riot and the oil painting of Millard Fillmore were pebbles tossed into water. The ripples they made widened until the warm waves of their company gently rocked him.

The roundness of stones in the bottom of a stream; the circular pattern of fishes’ scales. He sat in the silence of the huge office but pictured the triangular thrust of the Rockies with their beards of conical firs, shapes within shapes within shapes. Perhaps soon he would take a needed Colorado vacation. Perhaps one day he would do the unthinkable and retire.

“Sir? You hear me?”

“Yes.” He refused to turn around.

Muffled footsteps on the thick wool carpet. Natalie came into view behind his left shoulder, just inside the range of his peripheral vision. Her blouse, sewn from a material of disorderly, multicolored shapes, sent chills of disquiet down his neck. To avoid the sight of that blouse, he moved his gaze

“Who are the demonstrators?” he asked.

“Germans, French, some Scandinavians,” she replied, seating herself in the Louis XV chair next to his desk.

“What are they protesting?”

“The tariff bill. They think the Chinese and Koreans are about to undermine their economic freedom.”

There was a new box of pencils on his desk. He picked up the container and slid off the top. Inside, pencil ends nested like flat, hexagonal atoms. He drank in the scent of wood and graphite, running his finger down the first queue. “This,” he said fondly, “is freedom.”

Holding the corner pencil down, he upended the box, letting the others spill onto the desk. Then he righted the case and lifted his opposable claw from the single survivor. The pencil toppled from its pleasant upright alignment and fell against the side of its container. “That is freedom to you,” he said.

Natalie pondered the box, then picked up a pencil from the heap and dropped it, with a dull tap, in with the other. “It looked lonely,” she explained.

In the box the two pencils lay at an antagonistic angle. Yes, he had missed the point. Two crossed pencils were more symbolic of what humans judged to be freedom.

“There are plots to kill me,” he told her.

“I know.”

“Who could be behind it?”

“Anyone,” she said with a shrug. “Everyone.”

He peered down the long velveteen spread of the south lawn to the single army tank at the barricade and the advancing troops behind it. The helmets of the UN peacekeeping forces were an inappropriately cheerful sky blue. “They expect me to do something, but I don’t understand tariffs. And why should economics be so important?”

“Pocketbook issues always get people into a sweat.”

The White House chief, like all Cousins, was used to concrete answers. Good data, he felt, should line up in neat rows like pencils in a new box. “What specific pocketbook issues?” he asked, hoping she would come to the point.

“Oh, cheaper cars.”

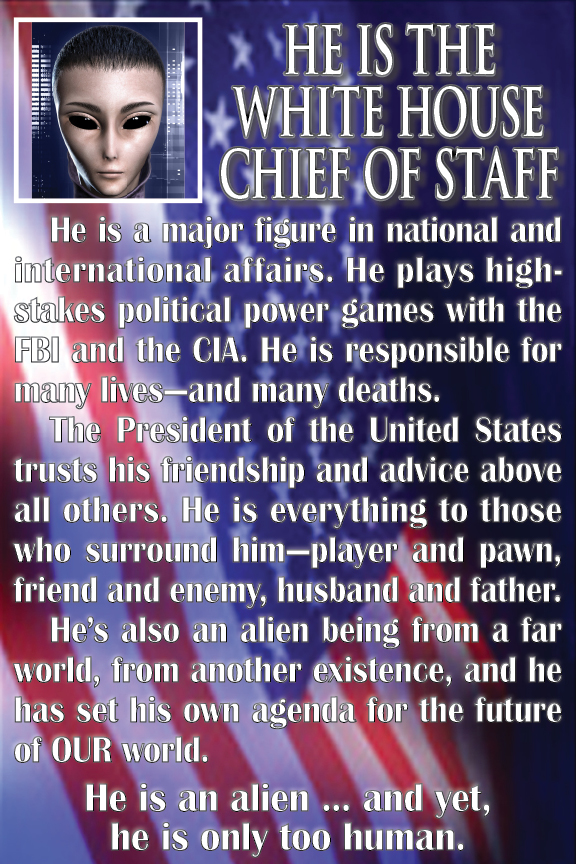

In the window his own image was superimposed on the riot, as though he had given it a seal of approval. His eyes were huge onyx almonds on a pale hot-air balloon of a head that seemed tethered above his black uniform. On his shoulder his insignia and nameplate gleamed.

“Cheap cars are unimportant,” he told her, “when compared to the peace of Communal thought.”

Light as a leaf drifting onto the surface of a pond, his attention settled on her. The colors of her blouse were hectic blues and reds and greens, the shapes ill-formed triangles that pointed, higgledy-piggledy, in all directions. “This blouse,” he said.

She touched her collar in evident surprise. “New. You like it?”

“Don’t wear it again. Muted colors, as I told you. Grays and blacks and navies.”

“Gray makes me look ten years older,” she argued. “And I spent good money on this blouse. You know, I could make a lot more in the private sector. I have great front-office appearance. Not, of course, that

you

would ever notice, but the senators do. You don’t pay me enough–”

He stood and lifted his hand as a signal that she had won the fight. Natalie, at five feet one-half inch tall, had been one of the few applicants his size. “Use the White House credit card to buy yourself another.”

“And a new pair of shoes.”

He cocked his head to the right in query.

“I bought shoes to match this blouse. So you owe me.”

“All right.”

“And a purse.” Natalie’s mouth was in a tight line. It was a dangerous expression, he knew. A sign of anger. Perhaps the blouse was a pocketbook issue.

“Buy whatever you like,” he said. She bared her teeth in a smile, and he began to wonder if he was being overly generous.

“Sir? Better get down to the basement.”

As he turned to go, the room assaulted him with its disorganized design, one that had no relationship at all to nature. Humans had a primitive idea of harmony. Only once had he seen the order of fractals in a piece of human art: a Renaissance oil that showed the subject standing next to a painting of the same subject and the same painting, copies of the large painting growing smaller and smaller until the final one was done in a suggestion of tiny brushstrokes.

Chaos, he thought as he strode across the presidential seal woven into the dark blue carpet. Chaos was going to kill him.

A BROODING

William Hopkins and a nervous Speaker of the House were lurking at the West Wing stairs. Dropcloths were spread nearby, and Secret Servicemen were gathered in a somber knot watching a pair of painters apply eggshell latex over three lines of graffiti on the wall. The red paint was stubbornly bleeding through the beige.

The sharp, aggressive strokes of the letters were plain enough, but the White House chief found the message bewildering:

BLACK UNIFORMS

LIGHTNING BOLT INSIGNIA

REMIND YOU OF ANYTHING?

Reen idly fingered the outline of the white lightning bolt on his chest.

“Reen,” Hopkins called. The FBI

director was smiling as he walked across the carpet. It

looked as though his hand was fighting an urge to pop out of his pocket and grasp Reen’s own, but Hopkins had worked with the Cousins long enough to have learned reticence.

“Director.” The chief of staff nodded. Then his gaze fell on the man behind Hopkins’s broad back. Of late the two habitually traveled together, the huge Bureau director and the diminutive congressman, as though the latter were a dog on his leash.

Reen searched his mind for the congressman’s name and then remembered the word association Marian had taught him: What was the sound a Chihuahua would make, dropped from a twelve-story window?

Oh, of course. “Speaker Platt,” Reen said before the FBI director’s form eclipsed that of the other man.

Hopkins’s sloping shoulders ballooned out into a puffy midsection, and his feet seemed too small to balance his bulk. As the man leaned over, Reen had the unsettling notion that he was about to be engulfed by a sofa.

Hopkins breathed whiskey-and-mint-scented breath into what he incorrectly imagined to be Reen’s ear. “Wanted to talk with you for a minute before we had to go down to the meeting.”

“Yes?”

“You know, I appreciate how you’ve adapted to us, but there’s some stuff that, talking man-to-man so to speak, you’re doing all wrong.”

Reen glanced around Hopkins’s looming bulk to the graffiti on the wall. The spiked letters, like slashes in the plaster from which blood oozed, bothered him more than the oblique message. There was implied violence in that calligraphy.

“Not your fault, of course. But I feel when you have things mixed up, it’s my job to set you straight. For example, it’s a well-known fact that if you give a woman any power at all, she’ll either cave in at the first sign of trouble or else turn into a ball-breaking bitch. Bless ‘em, they just can’t help it. You understand ‘ball-breaking’?” the director asked helpfully.

“Yes,” he replied. Hopkins’s references to body parts never ceased to fascinate Reen.

“The CIA,” Hopkins said. “You have to do something about the CIA. Cole’s on the rag, the vindictive bitch. Or maybe she’s menopausal or something. You have to back me, Reen-ja. She’s ripped the

cojones

right off some of my best agents. Probably made a victory necklace out of them.”

Hopkins was so tall that Reen was eye-level with the man’s tie. It was a nice tie, done in dark blue with small pink seashells lined up in neat rows across it. The only thing about the tie Reen found bothersome was that the lines were angled rather than horizontal or vertical. Why, he wondered, would the designer want to tip the pattern that way?

“Someday you’re going to look up,” Hopkins said, “and see she has a pair of gray

cojones

on that necklace, figuratively speaking. You understand the word

cojones?”

Reen wondered how much the FBI knew about himself and Marian Cole. Skirting Hopkins, he quickly descended the stairs.

The FBI director hesitated a moment before following, Speaker Platt at his heels.

“Cole’s got something on you, doesn’t she, Reen-ja?” Hopkins asked when he caught up. “You can tell me what it is. Maybe I can persuade the Bureau to help.”

Hurriedly, Reen changed the subject. “Why haven’t we been able to find out who is painting the graffiti on the walls?” Not much that was human frightened Reen; but the graffiti had him worried. It meant that someone close to him, someone in the White House itself, hated him enough to be a dangerous foe.

“Secret Service have their heads up their collective butts,” he said, deftly combining two body parts into a single image. “You know, one time when the downstairs was open, a tourist wandered in on Kennedy when he was having breakfast. Can you imagine?”

“I don’t wish to discuss Kennedy,” Reen said sharply. He wondered if Hopkins carried a pocket of hero worship in the multi zippered, confusing organ that was his human heart. If Hopkins loved the memory of Kennedy, he could be the author of the graffiti. Reen glanced at the director’s manicured hands but could see no evidence of paint.

When they reached the bottom step, Hopkins gave a quick, abashed grimace. He was huffing from the unaccustomed exercise, and his jowled face was an alarming shade of red. “Sorry. Nothing personal. So are we going to get together on this CIA thing?”

Without answering, Reen hurried to the cavernous situation room. The National Security Council had had time to become bored. Vilishnikov, head of the Joint Chiefs, was brushing dandruff from his red epaulets. Hans Krupner, the education advisor, was making an origami giraffe from a paper napkin. Krupner, it appeared, had gotten closest to the riots. His hands were still atremble, disturbing his efforts at folding. There was a bruise on his forehead.

At a corner of the U-shaped table, Marian Cole was carrying on a listless conversation with DiSecco of Finance. When she caught sight of Hopkins and Reen together, she shot the White House chief a suspicious look.

Marian was dressed in brilliant crimson, a color chosen to annoy him. And she was spotlighted by one of the ceiling’s recessed bulbs. The light, Reen noticed, was kind. The translucent skin of her cheek glowed pink, like the tender hue of the seashells on Hopkins’s tie.

Faced by her silent accusation, Reen hesitated. An instant later her blue eyes darted away, releasing him from the pain of her scrutiny.

Reen took his usual seat at one prong of the U to avoid being bracketed by the taller humans. Platt was standing indecisively, considering the only empty seat: the President’s. Finally the Speaker grabbed a folding chair from the wall and, with murmurs of apology, squeezed between Hopkins and an environmental consultant from MIT.

Vilishnikov began pulling papers from his briefcase and setting them on the table. “I have here a copy of the Tariff Regulation Bill. I thought we might go over it point by point. The President has five days left in which to sign. Five short days. Then it becomes a pocket veto, and I assure you, when that happens, Europe intends war.”

No one on the east side of the U was aware that the door was swinging open behind Vilishnikov. The west side instantly froze. DiSecco slid lower in his chair, as though preparing to duck under the table.

A marine sergeant in full-dress uniform stepped into the room. “Ladies and gentlemen,” he announced, “the President of the United States.”

In a show of conformity, the humans all stood, DiSecco having to pull himself up from his crouch. A Secret Serviceman was at the doddering President’s elbow. Age and the crush of responsibility had bowed Womack’s once ramrod-straight back. The face had withered to a deceptively sweet-expressioned skull. For a moment the Secret Serviceman and the President fought a small war over which way Womack was to turn. At last, gentle but persistent, the agent won; he led Womack to his seat at the head of the table, and the rest of the National Security Council took their chairs.

Reen stared down the table at the only other human he loved. Womack was drooling.

“War in Europe,” Vilishnikov continued.

Womack snored once, loudly. Everyone turned to the President. Womack’s eyes were closed; his mouth hung open; his head bobbled precariously. Quickly the Secret Serviceman eased him into a position where the presidential face would not drop to the National Security Council table.

“So. War in Europe,” Vilishnikov began once more, clearing his throat. “As a precautionary measure I have ordered our troops in this hemisphere to full alert–”

“Why?” Hopkins interrupted. “If the Europeans move, they’ll move east. To China. To Japan. To Korea. Who cares? What’s important are the disappearances. This month five of Reen’s people have turned up missing. That makes twelve so far this year.”

Marian Cole put down her coffee cup and smiled at the frustrated head of the Joint Chiefs. Her swept-back blond hair seemed to be rebelling against that morning’s hairspray. A lock of it hung above her right eye. “Don’t you worry, Arkady, honey. Billy takes over meetings the way a hog takes over an acorn patch. We’ll talk about your war if you want to.”

Hopkins’s small eyes narrowed further, to be nearly buried in frowning flesh. “Maybe Director Cole doesn’t want to talk about the disappearances because the CIA’s behind it. I suggest we start investigating over at Langley.”

“Try it. You talk a good game, Billy, but you’re proud-gelded.” Marian Cole coolly regarded the ceiling. “The will’s there, but the bang’s a dud.”

Hopkins smacked the table with his open palm. All the members of the NSC but Marian Cole, Reen, and the snoring President jumped in place.

“Two Cousins,” said the White House chief.

Hopkins turned to Reen, his jowls shivering, his expression that of utter disbelief.

“Ten Loving Helpers have gone missing this year, but only two Cousins.”

“Shit!” Hopkins shouted. “They’re still your people, aren’t they?”

Reen could not fathom why Hopkins was so enraged. “Yes, but–”

“Billy,” Marian said in an indulgent voice, “why don’t you just let me handle this? The CIA was taking care of all the alien business before. We have kind of a historical caveat.”

“Listen, Reen-ja.” Hopkins rose from his chair like a mountain thrust upward by plate tectonics. “The CIA has been working on ways to get rid of your people ever since the Truman administration. You know that. And they would have kept on if the budget had been funded.”

Reen took in the appalled faces around the table. Marian Cole was the only one who seemed calm. The lock of hair had fallen another quarter of an inch. There was a smile on her red lips.

“Oh, sit down, Billy,” she said with a wave of her hand. “The thing we should be talking about here is what the Cousins intend to do if Europe declares war and if the domestic terrorism isn’t stopped. What about it, Reen?” Her denim blue eyes twinkled. “You have the obvious weapons superiority. We’re a bunch of wing-clipped ducks in a lake. Why don’t you finish us off?”

Around the table a breathless, terrified silence. Krupner spasmed, accidentally decapitating his origami giraffe. He looked down at his guilty hands and the torn paper in dumbfounded woe.

“Jesus Christ,” Hopkins whispered to Cole. “Will you shut up.”

“Somebody’s got to have the balls to say it. What about it, Reen?” Marian asked.

Reen stiffened, feeling the tug of her nearness as a star feels the thieving pull of a black hole. Each time they were together, she stole more and more of him. He was a small creature growing even smaller, a being on the very edge of disappearance.

He fought to keep his treacherous mouth shut. Had they been alone, he would have told her. He would have answered any question, no matter how ugly the truth.

“Come on,” she said. “What are you guys waiting for?”

Hans Krupner burst into tears. “We have always the same meetings. Threats. Shouting. Everyone at one another’s throats. So this is the peace the Cousins promised us? I tell you, I cannot stand such peace anymore.”

At that moment the President rose. The NSC looked expectantly, encouragingly to Womack. Vilishnikov stared at the President with the wonder of a blind man catching his first glimpse of the sun.

Womack fumbled with his fly, took out his penis, and, before the Secret Serviceman could stop him, voided his bladder on the tariff bill. Urine splattered. Krupner forgot his tears and inched away from the spreading wet.

“Meeting adjourned,” Reen said, rising and heading quickly to the door. There he stopped and looked back. The members of the NSC were standing, gazing down at the urine-splattered papers. The humans were differing shapes, differing colors. Even in physical appearance they were chaotic. He felt he could read idiosyncratic fears and individual ambitions behind their tiny eyes.

“Does that count?” DiSecco asked. “Listen. Could we somehow construe that as a signature?”

Reen called, “Director Cole.”

Marian lifted her head.

She was angry with him, he knew; and that was to his great regret. On the other hand, she didn’t have the courage to refuse his direct order.

“I will see you now in my office.”