Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management (32 page)

Read Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management Online

Authors: Devdutt Pattanaik

The aarti ritual is conducted daily, for every day we need validation of who we are. And to ensure it does not become monotonous or thoughtless, festivals are organized where the same offering is made rather lavishly to the sound of music and the smell of incense. At the end of the ritual, the devotee asks the deity for a favour.

In temples, the aarti is not restricted to the presiding deity. Aartis are done to all the subsidiary and satellite shrines, even the doorkeepers of the shrine, the consorts and the vehicle or vahana. Everyone is acknowledged and praised, no one is invalidated. This increases the chance of divine intervention.

Is an aarti and bhajan strategic or sincere? Is praise by bosses strategic or sincere? We will never know. What matters is that it makes a difference to the subject being admired. No one ever complained when occasionally they found themselves being praised.

Farokh, the team leader of a media company, knows the value of praise. He introduces each member of his team as 'an expert', 'stalwart' or 'key member'. He remembers every little achievement of theirs. When Sanjay walks into a meeting, he beams when Farokh says, "Here comes the guy who stayed back late last week to get the files downloaded for client presentation." Shaila, the trainee, is thrilled to hear Farokh declare, "The way Shaila maintains records of client meetings is laudable." Through these words, Farokh empowers his team, makes them feel valued and important. It reveals they are not invisible performers of tasks. They are people who matter. His praise fuels them and they go that extra mile at work. But just as bhajans do not work without bhakti, praise does not work unless it is genuine. Whatever Farokh says is true. None of it is a charade. He constantly looks at what to admire in every person he meets. No person is perfect, but everyone has something of value to offer. It may seem insignificant to others but it becomes significant when noticed. That Ali always calls his wife at lunchtime has no corporate significance. But Farokh turns it into office fuel when he remarks in front of everyone, "I wish my daughter gets a husband as caring as Ali." It makes Ali blush. He feels happy. And in happiness, he delivers more.

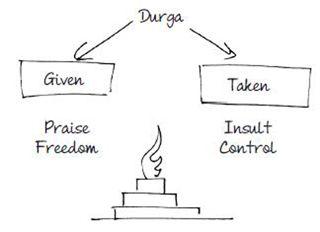

Insults disempower us

In many Hindu temples, at least once annually, the devotee does ninda-stuti and ritually abuses the deity for failing him. This is a cathartic exercise, a safety valve. It is a reminder that the deity has no mental-image; it needs no Durga to sustain it. It is also a reminder that the devotee has a mental-image that feels deprived or denied when the deity does not satisfy a desire.

An animal in the forest does not resent or begrudge anyone. The predator does not complain when it fails to catch its prey, or when the rival drives it out of its territory. The prey does not jeer at the predator after outrunning it. Animals simply move on with life. Humans often consider their desire to be their due and expect life to provide them with whatever they yearn for.

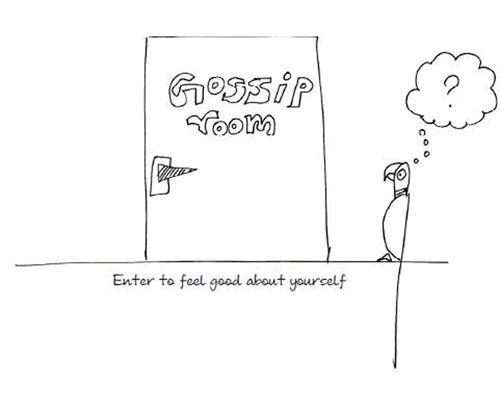

Ninda-stuti is the equivalent of office mockery or 'backbiting' or complaining (colloquially called bitching) about the boss. A yajaman understands its source and allows it to thrive as it relieves tension, helps the employee experience the delusion of power. Gossip serves the same purpose. By pulling down or mocking someone else, by imagining the Other to be inferior, we empower our mental-image. Jokes come from the same place—a narrative that grants superiority to the person hearing the joke over the person who is the subject of the joke.

During her coffee break, Reshma goes to the cafeteria and sits with the other office girls. After initial pleasantries, the topic shifts to the team supervisor: how she dresses, how she speaks, how she curries favours with the bosses, how she got promoted, how she travels. No one has a kind word for her. They see her as a monster. Sometimes, the girls talk about their experiences with callers: the accents, the demands, the time spent on inane matters. At the end of these short but spicy conversations, Reshma feels fresh and invigorated, full of Durga, strong enough to handle the monotony of her daily job. She looks forward to these meetings with the girls.

Comparison grants us value

The Mahabharat tells the story of Kadru and Vinata, the two wives of Kashyapa. Kashypa was one of the many sons of Brahma. Kadru asks to be the mother of many sons. Vinata asks for mighty sons. Kashyapa blesses them both. Kadru lays a thousand eggs while Vinata lays only two. Why does Kadru seek many sons? Why does Vinata seek mighty offspring?

The answer lies in mental image. It is not enough being the wife of Kashyapa. What matters more is knowing who is the preferred wife. Kadru feels many sons will get her more attention. Vinata feels mightier sons will get her more attention. Each wife wants to be envied by the other, and thus be in a dominant position. We yearn to be mental alphas of an imaginary pack. When we are envied we feel superior and powerful.

Kadru becomes the mother of serpents. Vinata becomes the mother of eagles. Serpents eat the eggs of eagles and the eagles feed on serpents. This eternal enmity is traced to the desire of the mothers to measure, hence evaluate ergo dominate.

Venu was happy he went to the business school that was ranked fifth while Raghav went to a business school that ranked seventh. He was happy that he got a placement before Raghav. He was happy that his first salary was more than Raghav's. He was happy that he got a promotion earlier than Raghav, but then Raghav started his own business and it was a success. Suddenly, Raghav is his own boss; he may not make as much money but he is answerable to no one. Venu now hates his life. He has fallen in the measuring scale. He is unable to see himself without comparing himself to Raghav. He lives in the world of measurement: the matrix called maya.

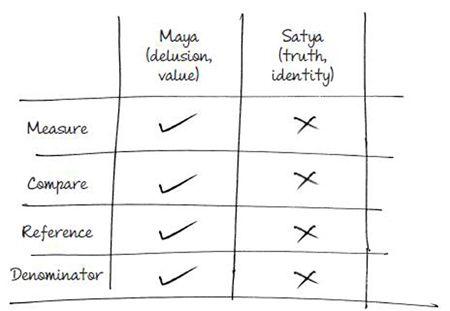

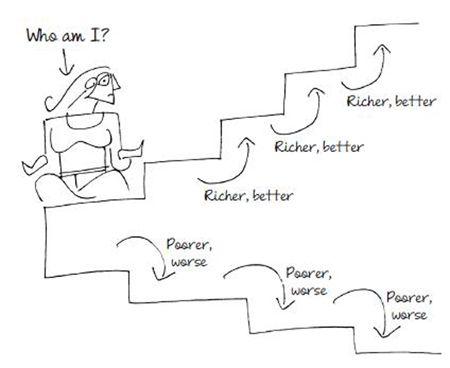

Comparison is a powerful tool to identify ourselves and locate ourselves in a hierarchy. Comparison means measurement. In Sanskrit, the word maya or delusion is rooted in the sound 'ma' meaning 'to measure'. For a world seen through measurement is delusion.

Maya and satya are opposites of each other. Both are truths, but maya is truth based on comparison while satya is truth not based on comparison. Maya allows for judgment, as there is a reference scale; satya does not.

In nature, everything is perfect at every moment. Everything has a place and purpose. Nothing is better or worse. A bigger animal is not better; it simply has a higher chance of survival. But in culture, measuring scales are geared not towards survival of the species but towards the validation of our mental image. Measuring scales are designed to include and exclude, create a hierarchy. Measuring scales can grant us Durga if they favour us, and strip us of power when they do not. In nature, nothing is good or bad, right or wrong, higher or lower. Everything matters. Everything is satya.

On the other hand, marketing and business is all about maya. In interviews we rank candidates using measuring scales. In markets, we rank products using measuring scales. We give compensation and bonuses and perks based on measuring scales. The world of sanskriti is all about maya. The social body feeds on maya. Maya has the power to make us feel powerful and powerless. In culture, some things always matter more than others.

We seek hierarchies that favour us

When he is made chakravarti of the world, Bharat, the eldest son of Rishabh, expects all his brothers to bow before him. Rather than bow, most renounce the world and become Jain monks. One brother, however, refuses to bow or to renounce. His name is Bahubali, the second son of Rishabh. Bharat declares war on Bahubali. To avoid unnecessary bloodshed, the elders recommend that the brothers engage in a series of duels to prove who is stronger. Bahubali turns out to be stronger than Bharat, but a point comes when Bahubali has to raise his hand and strike Bharat on the head. The idea of striking his elder brother disgusts Bahubali. Instead, he uses his raised hand to pluck hair from his own head, thus declaring his intention to be a Jain monk like his younger brothers.

Since Bahubali has renounced the world after his younger brothers, he is a junior monk and is now expected to bow to the senior monks, his younger brothers included. Bahubali finds this unacceptable. Surely it is the other way around, and younger brothers should bow to their elder brothers? However, in the monastic order the rules of seniority are different.

Every organization has a structure; every structure has a hierarchy. In some organizations this is determined by the duration of employment, or merit, or closeness to the owners, and in yet others, it is determined on the basis of the community, gender or institution one belongs to. The conflict comes when the hierarchy of the organization does not match the hierarchy of the mind.

Bahubali struggles. He became a monk to avoid bowing to his elder brother and ended up having to bow to his younger brothers. And yet, being a monk is not only about renouncing the social body but also renouncing the mental body. It is easier to give up material things and one's status in society, far harder to give up the thought of domination.

When Rahul joined as the assistant manager of a shipping firm, he was told that two people, Jaydev and Cyrus, would report to him. Jaydev and Cyrus were senior by many years and they found the idea of Rahul signing their appraisal forms unacceptable. Rahul did not see what the problem was, surely the system had to be respected. Like Bahubali, he realized the problem when he was asked to report to the owner's son, Pinaki, who, though senior in years, was neither as qualified or as smart as him. Jaydev and Cyrus could not handle reporting to a younger man. Rahul could not handle reporting to a man he thought to be less smart than him. Both had to struggle between the desire to dominate and the rules of domestication.