Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management (36 page)

Read Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management Online

Authors: Devdutt Pattanaik

Rules

Any organization is essentially a set of rules. Rules help humanity overpower the law of the jungle that might is right. Rules domesticate the human-animal. But the human-animal can use rules to dominate and reinforce his position as the alpha. The human-animal can also pretend to follow rules, be subversive, or revolt when opportunity strikes. There is much more happening with rules. For life becomes work when we have to live by another's rules.

There are no thieves in the jungle

Once Uttanka was travelling through the forest carrying a pair of jewelled earrings secured from a king called Saudasa. These earrings were the tuition fees he had promised his guru's wife. On the way, serpents stole the earrings. Uttanka was so angry that he invoked Agni, the fire-god, and filled Bhogavati, the land of serpents with so much smoke that it blinded them all. The torture continued until Vasuki, the king of serpents, returned the earrings to Uttanka.

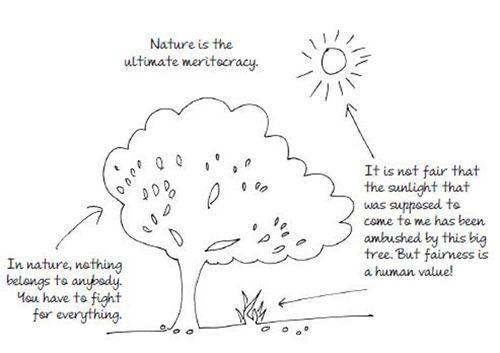

Uttanka saw the serpents as criminals; the earrings 'belonged' to him. The serpents saw Uttanka as the dominant beast who had defeated all rivals and claimed its prey. The human gaze is different from the animal gaze, as it assumes the existence of cultural structures like rights, rules and responsibilities. In nature, there is no concept of possession or property hence there is no thief, police, or court of law.

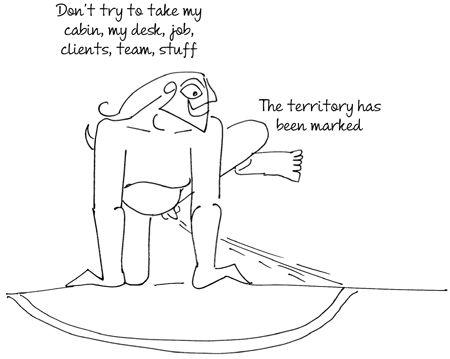

In the jungle there is territory not property. You cannot steal territory. You cannot bequeath it to children and loved ones. You have to fight for it. Winner takes it all.

In the jungle there is no law, no criminal, no rights, no duties, no judge, no jury. Everyone is on their own.

Brahma rejects this world. He wants a place where his possessions are protected and respected. This is the world of rules; this is sanskriti. In the world of rules there are rule-breakers, the criminal, the corrupt. There is need for a police force, an auditor, and a regulator. They ensure that the rights of the weak are respected by the strong.

Shabbir smiled. One day, a man seated in a bus spat on the car he was driving and his boss got very angry. He rolled down the window and abused the man, calling him ill-mannered and low-class. The very same day a bird flying over the car relieved itself on the window screen. The boss was upset but he could not shout at the bird. The bird would not understand what manners or class meant.

Without rules there is territory, not property

Apsaras, the nymphs who live in Indra's land, do not follow any rules. They subscribe to no law. They live in absolute freedom. In the Mahabharat, when Urvashi, an apsara, tries to seduce Arjun, he withdraws from her stating that she is like a mother to him for she had seduced and stayed with his ancestor, Pururava. She argues that she is ancestor to no one; she belongs to all. The rules of man do not apply to her, a nymph, she says. "But they apply to me," says Arjun.

Urvashi represents prakriti to whom rules do not apply. Arjun, on the other hand, belongs to sanskriti—the world of rules. With rules comes the notion of ownership and property. In nature, the strongest or the smartest gets the prize whereas in culture, thanks to rules, even the weak get something.

In the Ramayan, when Gautam finds his wife Ahalya in the arms of the more attractive and more powerful Indra, he curses Indra's body to be covered with sores and he curses Ahalya, turning her into stone. Gautam may not be the strongest, smartest or richest man; he may not even be a worthy groom, but by law he is the husband, none but he has the right to be with his wife, and the same is expected of her. By law, Indra is a thief who has violated the rules of sanskriti. By law, Ahalya has committed the crime of adultery for failing to respect the rules of marriage. These accusations would make no sense to an apsara like Urvashi.

Rules establish sanskriti. They are put in place in the hope to create a world where even the weak can thrive and the helpless have rights. Unfortunately, rules end up creating a new form of hierarchy, one that is not based on force, or cunning, but rather based on the whims of man.

Thus, in some organizations one gender is favoured over another, or a certain community or nationality is favoured over another. All these decisions are rationalized using complex arguments. We strive for meritocracy until we realize that it comes at a price that humans are unwilling to pay.

Initially, the parking lot outside the temple was free for all. Dozens of cars could be seen parked outside as hordes of families visited, especially on the auspicious Fridays and Saturdays. Soon, the number of cars increased so much so there were fights in the parking lot between people vying for the same space. Finally, to keep the peace, rules had to be introduced: it was first come first served. Those who came late had to park outside on the road and risk having their cars towed away. This inconvenienced many powerful and rich people in the area who complained to the temple committee and even subtly threatened to withdraw their financial support. The temple authorities decided to reserve a portion of the parking lot for VIPs. This only created more trouble: who was a VIP and who wasn't? The founding family of the temple, who were of modest means, demanded more rights than the rich donors. Politicians began to assert themselves and also demanded special rights. When these were denied, the temple suddenly found itself being questioned by the local municipality about the legality of its reserved parking. The inquiry stopped when the local legislative council member was given a VIP pass. In the absence of rules, there is chaos. In the presence of rules, there is order. But the order is constantly threatened if it fails to cater to the dominant alpha. With order comes hierarchy.

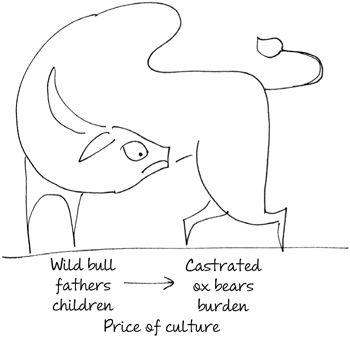

Rules domesticate the human-animal

Domestication is a violent process. In the Ramayan, Surpanaka is a free spirit who seeks intimacy with Ram. When he introduces her to Sita, Surpanaka sees her as a rival. She is unable to fathom the meaning of marriage and fidelity. These rules make no sense in the jungle. In the jungle, the strongest and the most beautiful gets the mate. So Surpanaka tries to take what she wants by force. She decides to attack Sita hoping that with the wife out of the picture, Ram will succumb to her.

To protect Sita from harm, Lakshman intervenes and pulls Surpanaka back. He then cuts off her nose, disfiguring her, making her less worthy of anyone's affection. With this act, the threat to the laws of the marriage is wiped away. The wild beast is domesticated. Order is restored.

From Lakshman's point of view, one informed by culture, he has done the right thing. From Surpanaka's point of view, she has been humiliated and invalidated. She may behave like an animal but that she feels anger indicates she is not an animal. She is human. Her mental image has taken a severe beating. Lakshman may think he is a hero for upholding the rules of culture, but he has only fuelled Surpanaka's fury. On her part, she feels like a victim, not a villain.

Those who make the rules and enforce them always feel powerful and righteous. Those who are obliged to follow the rules do not feel so. They comply willingly only if they feel good about the rules, else they quietly submit. Then there are some who disagree with the rules, rightly or wrongly, and they feel powerful by breaking them.

The hospitality firm and the builder had a joint venture. The hotel had been built by the builder but he did not know how to run the hotel. So the management was outsourced to the hospitality firm. Vikrant was the hotel manager and he soon had a problem. Sanjay, the son of the builder, would come to the bar every evening and simply grab cash from the counter. When the cashier tried to resist, he would say, "Don't you know who I am? I own this building." This had to be stopped. So Vikrant called his bosses in the head office and apprised them of the situation. "I can stop the bully but only if you give me full support." The bosses assured him full support. The next time Sanjay tried to grab cash, Vikrant and two of his managers intervened and stopped him. Sanjay threatened them with dire consequences. Vikrant pulled out his mobile and called Sanjay's father and said, "Sir, I have been told by the management to withdraw operations if Sanjay continues to misbehave with the staff and interfere with processes. Please advise on what needs to be done." The reply made Vikrant smile. Sanjay left the bar shamefaced and never returned again. Surpanaka had been controlled by rules. But Vikrant knew that this would come at a price. The builder's prestige had been dented and it could sour the relationship with the hospitality firm, create trouble in the future. Vikrant's bosses knew it too. He was transferred to another hotel and secretly given a cash bonus not to speak of the incident. And because Vikrant displayed immense maturity, his bosses marked him out as talent.

Domestication can be voluntary and involuntary

Garud was born a slave. His mother, Vinata, had lost a wager with her sister, Kadru, as a result of which she and her offspring were obliged to serve Kadru and her children, the nagas. "If you want to be free," say the nagas to Garud, "fetch amrit for us."

Garud immediately flies to Amravati and finds the pot of amrit there, guarded by the devas. He spreads his mighty wings, extends his sharp talons and swoops down on them. Indra and the devas are no match for Garud. He shoves them aside and claims the pot with the nectar of immortality.

On the way back, he encounters Vishnu. Vishnu says, "There is a way by which you can get your freedom without giving the nagas the amrit. If I tell you how, what will you give me in exchange?" Garud swears to serve him for the rest of his life.

Vishnu then says, "After you give the pot of nectar and secure your freedom, tell the nagas they must bathe before drinking it. They will leave the pot with you, assuming you will safeguard it until their return. Allow Indra to reclaim the pot while the nagas are away. When the nagas question your actions, remind them that you stopped being their slave as soon as you gave them the pot of nectar and were thus under no obligation to stop Indra from stealing what anyway belongs to the devas." Garud does as he is told: he gets his freedom, Indra gets back the amrit and the nagas get nothing. Indra is so pleased with Garud that he makes nagas the natural food for Garud. Garud then goes to Vaikuntha and serves Vishnu.

In this story, Garud resents serving the nagas while he willingly serves Vishnu. The former is involuntary domestication. The latter is voluntary domestication. In involuntary domestication, we are compelled to work according to other people's rules. In voluntary domestication, we choose to work according to other people's rules.

We voluntarily give up our rules and agree to follow other people's rules, if they grant unto us something that we value. The contract we sign when joining an organization is voluntary domestication.

Srikanth always comes to office on time. He likes coming early and setting up his desk before others. Then, one day, the company introduces the swipe-card system to ensure everyone comes on time. Suddenly, Srikanth does not feel like coming early. He hates his integrity being watched and measured. So he comes to office exactly on time and leaves on the dot too, never giving that extra time that he did before the company made domestication so involuntary. Srikanth would be servant to a trusting Vishnu, not to an exploitative naga.