Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management (39 page)

Read Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management Online

Authors: Devdutt Pattanaik

Markandeya has the boon of immortality, yet he feels great fear. One day, he sees the rains fall and the oceans rise until the whole world, every mountain, continent and person he knew, every village and city he'd visited, get dissolved. The sun disappears from the sky along with the moon, the stars and every cloud. Markandeya finds himself surrounded by vast, limitless water. Alone in the midst of nothingness, Markandeya experiences great dread. There is no one to see him or call him by his name. Without the world, who is he? He has no identity. Does he even exist?

As these thoughts cross his mind, he sees a banyan leaf floating on the waves. A child is sitting on the leaf and gurgling happily, sucking his big toe joyfully. The child breathes in and Markandeya finds himself being sucked into the child's body. Inside, he can see the entire universe—the sky, the earth and the underworld. He sees the realms of devas, asuras, yakshas, rakshasas, nagas, and manavas, some of whom recognize him and call him by name. Markandeya feels secure, his identity and value restored. All the fear that Markandeya experienced now disappears, thanks to the intervention of the child, who is undoubtedly Vishnu. Then the child breathes Markandeya out. He is back in the realm of the waters, of nothingness, where his fears return.

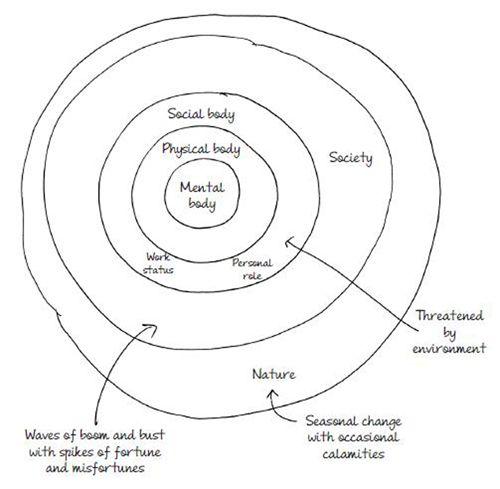

Markandeya's physical body may be immortal, but when the world around him collapses, his social body dies. He is stripped of all relationships, titles and status. He belongs to no hierarchy; is a nobody. That is why we cling to social structures around us: hierarchy, the rules of an organization, these grant us our identity and meaning. Sanskriti exists to make humans feel secure. That is why any change in society frightens us.

Our social structures depend on the organization. The organization depends on industry, which in turn depends on the market. The market depends on society, which in turn relies on the environment. All these are susceptible to change, and so are constant threats to our physical, social and mental body. We are only comfortable with change that nourishes our social body and reinforces our mental image. This constant, looming threat to our social beings is an eternal source of stress.

For ten years, Rupen handled the accounts of the jewellery factory where he worked. He did his job well and loved the routine of his life. Everything was familiar and in order. His boss, Motwani, loved him and his job was assured. Then Motwani died and his wife, unable to handle the business, sold it to a large conglomerate. Suddenly, all certainty disappears from Rupen's life. He has a boss to report to and is now seen as an old-school accountant who does not fit into the new way of thinking. With the end of one sanskriti and the rise of another, the social body also needs to die and be reborn, locate itself in the new structure.

We want organizations to secure our social body

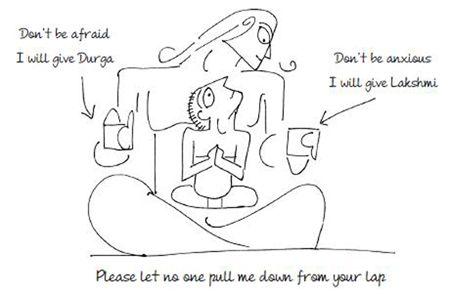

A little boy called Dhruva is pulled down from his father's lap by his stepmother. Feeling deprived and denied, he seeks a father from whose lap he will never be pulled down. He prays fervently until Vishnu picks him up and places him in his lap. There he sits in the sky, on Vishnu's lap, as the steadfast Pole Star. No one can pull him down.

We yearn for permanence in structures, systems and rules, as it reassures us about the permanence of who we are. When bosses change, organizations get restructured, when new teams are formed, when we are moved to another department, fear envelopes us. Like Dhruva, we hope there is a Vishnu out there, a parent who will always keeps us in his lap.

In medieval times, many wars were fought between the Mughals and the Marathas, but both agreed on one thing: the role of the king. For the Mughals, the king was jahanpanah—shelter of the world; for the Marathas, he was chattrapati—bearer of the umbrella that protects us from problems. The king was seen as one who grants security, not just physical but also social security that assures us of our meaning.

People are often loyal to bosses or to an organization because it guarantees them both livelihood and social status. Many see this as a fair bargain, a social contract. Some people believe that a leader should provide security actively like a cat that carries her kittens by the scruff of their neck to safety. Others believe a leader is there to provide security passively in the way baby monkeys cling to their mothers to feel secure.

Underlying this belief is the assumption that we are dependent and we need not be dependable. Most devatas want to remain Dhruvas, few want to grow up and be Vishnu for others. We do not wish to rise in the varna ladder. We are comfortable being karya-kartas and not becoming yajamans.

All his life, Sudha wanted a permanent job like her brother, Sai, who worked for the government, but it never happened. First the company she worked for got shut down. The next company shifted office three times. Then her boss changed, after which the company was reorganized and she was given various roles over a span of two years. She was never able to settle down, feel a sense of stability or order. When she complained and told her brother how lucky he was, he moaned, "Not quite. I have been transferred to three cities in the past ten years and now I have to use all my influence to avoid the next transfer." Both siblings are like Dhruva yearning for a lap from where no one can pull them down.

We resist anything that is new

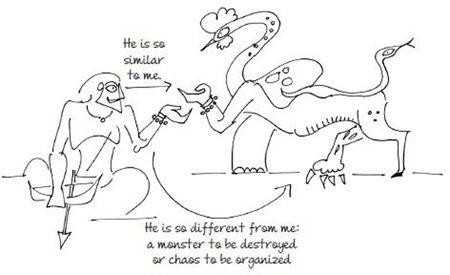

This story comes from the Oriya Mahabharat. One day, Arjun sees a strange creature in the forest, one he has never seen before. At first, Arjun thinks it is a monster and raises his bow to kill it. All of a sudden, he notices a human hand and realizes the creature is not as unfamiliar as he thinks. On closer observation, he finds Navagunjara, the creature with the head of a rooster, neck of a peacock, back of a bull, waist of a lion, tail of a serpent and the four limbs of a human, deer, tiger and elephant. Every part is familiar but not the whole. Why did he assume the creature was a monster simply because it was not something he had encountered?

Often, we see the world full of predators and rivals threatening our business and us. We condemn unfamiliar markets as being chaotic and unethical. We want to dominate, domesticate or destroy the unfamiliar, rather than understand it. We assume what we know is the objective truth and everything else is threatening. Yet, it is the unfamiliar that offers us the opportunity to grow. We need to seek the familiar in the unfamiliar and allow ourselves to embrace the new. Rather than seek control of the union it is important to include and assimilate the unknown.

When Christopher first came to Mumbai, he was frightened. The roads were bad, traffic was all over the place, there were crowds of people everywhere, slums poured out of every corner, there was construction work wherever he turned; so different from back home where there were hardly any people on the road, where streets were neatly arranged, everyone drove cars, and poverty was practically non-existent. For Christopher, Mumbai felt like a monster that needed to be killed or tamed, until he noticed that the people he dealt with were no different from the people in his native land, kind as well as complex. They argued, negotiated and offered solutions. In Mumbai, he discovered a market for his company, a much-needed lifeline. This was different. It had to be different. In the difference lay new ideas, new thoughts and new challenges. Slowly the fear dissipated. Navagunjara need not be feared; it has to be admired and understood.

We want to control change

In the

Kathsaritsagar

, Vikramaditya hopes to rule forever by asking that he die only at the hands of a child borne by a girl who is only two-and-a-half years old. The impossible happens. One day he encounters Shalivahan whose mother is barely two-and-a-half years older than him. His father is Vasuki, the king of serpents. In a duel that follows, Vikramaditya is killed and his glorious reign comes to an end.

Hindu mythology is replete with stories where the impossible happens. Asuras demand boons that make killing them near impossible, and yet someone finds a chink in the perfect armour and they end up dead.

We create structures, systems and rules that we are convinced are perfect and will last forever, but they never do. Eventually, inevitably, they do collapse. Ultimately sanskriti is no match for prakriti.

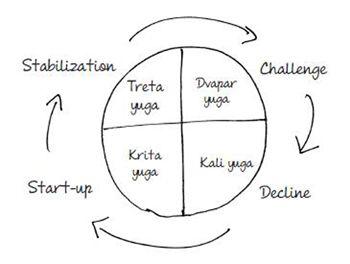

Buddhism keeps describing the world as impermanent. Hindus saw time as cyclical, each cycle a kalpa composed of four yugas, marking childhood (Krita), youth (Treta), maturity (Dvapar) and old age (Kali) before death (pralay), which is followed by rebirth. And yet, Indra craves amrit and the asuras do tapasya, seeking immortality.

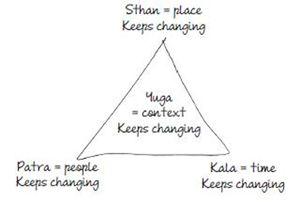

Organizations go through cycles and restructuring repeatedly. Change in market conditions, a new boss, target, merger, acquisition, etc. happens constantly, changing everything around us. Change can be upstream (bosses, investors, regulators) or downstream (employees, customers). Change can be central (strategy) or peripheral (market conditions). We ourselves can change, struck by boredom or desire. Still, everyone hopes to secure their position like Vikramaditya, getting upset when Shalivahan invariably appears.

Shekhar likes people who are organized and compliant. Organized and obedient people get ahead in his organization. Now the market is changing, and old familiarities are going out the window. He needs people who can think in the absence of structures, who can be proactive and take on-the-spot decisions. He needs kartas. But over the years he has groomed only karya-kartas. They ensured his success for a long time, but in the new market he needs kartas and there is no one around.