Read Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management Online

Authors: Devdutt Pattanaik

Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management (40 page)

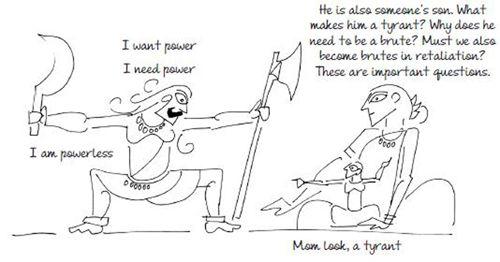

Insecurity turns us into villains

In the Bhagavad Gita, Kansa is foretold that his sister's eighth child will be responsible for his death. So he goes about killing all her children as soon as they are born in the hope of defying fate. In the Ramayan, as Ram's army nears Lanka, Ravan gets increasingly intolerant and demanding. When his brother, Vibhishan, pleads with him to let Sita go to save Lanka, Ravan views this as an attack on his mental image and kicks Vibhishan out. On the other hand, Ravan starts to increasingly rely on Kumbhakarn who does not challenge his mental image and keeps agreeing with him.

In the Mahabharat, Duryodhan tries to poison Bhim and sets fire to the palace in which the Pandavs are sleeping. He believes that with the Pandavs gone, his claim on the throne of Hastinapur will be secure. He wants to be king. He needs that social body and will do anything to destroy those who threaten it. Kansa fears for his physical body, Ravan for his mental body, and Duryodhan for his social body. In their own eyes, they are victims, fighting for survival. None accepts that death is inevitable.

Here, death is a metaphor for change. We do not want to accept the inevitable—that one day we will be replaced. We go about ensuring there is no rival, or threat to our existence. We create structures and systems that secure our roles, hence our self-image. But in securing ourselves, we end up hurting others. We become villains.

Rakesh thinks he is very smart. He can compute better than others and can organize things better than anybody else. If anybody challenges his system, he gets furious. He does not appreciate criticism, viewing it as opposition and a challenge. Smart people leave his team or sit there resenting everything he says, allowing him to make stupid mistakes, because they know he will not listen. Rakesh is a bully, he needs to be aggressive and dominating because this enables him to get Durga forcibly from people and feed his own sense of inadequacy. In doing so, he destroys all relationships. He remains alone and vulnerable, with no one around to help him when he really needs support.

Our stability prevents other people's growth

When Jarasandha, king of Magadha, learns that Krishna has killed his son-in-law Kansa, the dictator of Mathura and that the people of Mathura rejoiced at his death, he is furious. He orders his army to kill Krishna and set aflame the city. Krishna and the people of Mathura are forced to take refuge in the faraway island of Dwaraka.

Years later, after the Pandavs build the city of Indraprastha with the help of Krishna, Yudhishtir, the eldest of the Pandav brothers, declares their desire to be kings. Krishna says, "As long as Jarasandha is alive that is not possible. Jarasandha has subdued all the kings of the land. Until those kings are liberated, until they are free to attend your coronation and recognize your sovereignty, you cannot be king."

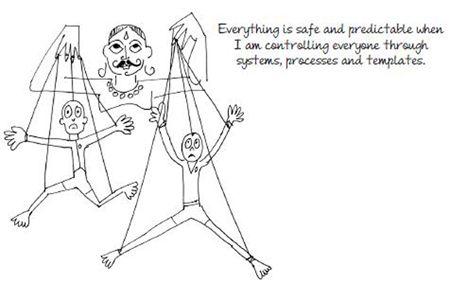

Jarasandha is a chakravarti, an emperor of all the lands he surveys. In Jain chronicles he is prati-vasudev, the enemy of vasudev (Krishna) and his pacifist brother baladev. Jarasandha's control and systems do not let other kings thrive. He may have established stability and order but the stability and order serve him, not Krishna or the Pandavs. Naturally, the vasudev considers the chakravarti as the prati-vasudev.

Without realizing it, our structures end up curtailing innovation. Innovators hate institutions and yet institutions are built on the principles of fairness and equality. In an equal world, no one can be special. An innovator, though, sees himself as different. From his different point of view come new ideas and innovation that will change the old order of things.

We call the innovator a rebel because he does not align with authority. We call the innovator a prophet because he challenges authority. But eventually, every innovator becomes a chakravarti and institutionalizes his rules. And with that he becomes a prati-vasudev or enemy to young entrepreneurs and other innovators.

Revant liked the licence raj era when business was assured from the government. Now, with liberalization he has to give tenders every year, deal with officers and prove his capability time and again, as the officers keep changing. They say this competitive environment is good for the country. But weren't the services he provided of top quality? What Revant does not realize is that because of the old system, many talented businessmen were denied opportunities to grow. They, in turn, resented the likes of Revant whose family had benefitted from British rule and subsequently, under the socialist governments. Revant saw himself as a chakravarti who creates order and stability around him. But ambitious men like Bilvamangal saw him as old money that does not like new money: a prati-vasudev, who uses his power to create rules that block others from rising.

We would rather change the world than ourselves

Shishupala was born deformed with extra limbs and eyes. The oracles revealed that he would become normal the day he was picked up by a man who was destined to kill him. That man turned out to be Krishna. Shishupala's mother begged Krishna to forgive a hundred crimes of her son. Krishna promised to do so.

At the coronation of Yudhishtir, Shishupala insulted Krishna several times. Krishna did not say anything and kept forgiving him, but eventually, after the hundredth insult, Krishna was under no obligation to forgive the lout. He hurled his Sudarshan chakra and killed Shishupala.

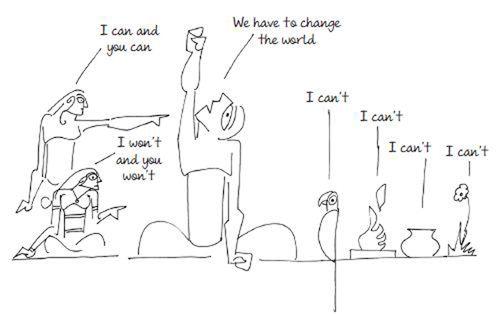

While Shishupala's mother got an assurance from Krishna, at no point did Shishupala's mother tell her son never to upset Krishna. Shishupala's mother gains Durga from Krishna but does not invoke Shakti in her own son. She relies on external powers for protection and has no faith in internal power. The burden of invoking inner power is too great. It demands too much effort. Like Indra, Shishupala's mother seeks external intervention to save her during crisis.

In the Puran, Indra never changes. Despite crisis after crisis and the repeated attacks of asuras, he does not change. He keeps asking for help from his father Brahma who asks Vishnu for help. When Vishnu solves the problem, Indra returns to his indulgent ways. We want problems to be solved, but we refuse to develop divya-drishti or realize that we want to change only the objective world and are convinced the subjective world needs no improvement.

When Atul resigned and moved to another firm, Derek was furious. He raved and ranted about Atul's lack of loyalty and his betrayal. "We should never hire professionals," he told his son. In his rage, he gave more powers to those who were loyal to him, not realizing that it was precisely this behaviour that had alienated the very-talented Atul. Derek's insecurity meant he was always suspicious of people who did not demonstrate loyalty. He wanted to hedge his bets and so gave equal value to those loyal as well as those who were talented. He wanted the world to be loyal to him, but did nothing to evoke loyalty in men like Atul by giving them the freedom and space they needed to perform. He believed, like Shishupala's mother, that the problem was with the world.

When the context changes, we have to change

Vishnu is at once mortal and immortal. Each of his avatars goes through birth and death, yet he never dies. The avatar adapts to the age. Jaisa yug, vaisa avatar (as is the context, so is the action). With each avatar his social body undergoes a change. He is at first animal (fish, turtle, boar, half-lion) and then human (priest, warrior, prince, cowherd, charioteer).

When Hiranayaksha dragged the earth under the sea, Vishnu took the form of the boar Varaha, plunged into the waters and gored the asura to death, placing the earth on his own snout, raising it back to the surface. This confrontation was highly physical.

Hiranakashipu was a different kind of asura. He obtained a boon that made him near invincible: he could not be killed either by a man or an animal, either in the day or in the night, neither inside a dwelling nor outside, nor on the ground or off it, and not with a weapon or tool. To kill this asura, Vishnu transformed himself into Narasimha, a creature that was half-lion and half-human, neither man nor completely animal. He dragged the asura at twilight, which is neither day nor night, to the threshold, which is neither inside a house nor outside, and placing him on his thigh, which is neither on the ground nor off, and disembowelled him with his sharp claws, which were neither weapons nor tools. This complex confrontation was highly intellectual, a battle of wits if you will.

Then came Bali, an asura who was so noble and so generous that his realm expanded beyond the subterranean realms to include the earth and sky. To put him back in his place , Vishnu took the form of the dwarf Vaman and asked him for three paces of land. When Bali granted this wish, the dwarf turned into a giant and with two steps claimed the earth and sky, shoving Bali back to the nether regions with the third step. This battle involved not so much defeating the opponent as it did transforming oneself.

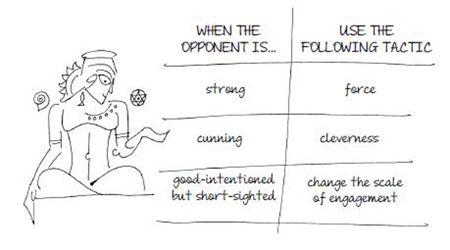

A study of these avatars of Vishnu indicates a discernible shift in tactics. From Varaha to Narasimha to Vamana there is a shift from brute force, to brain over brawn and, finally, an exercise in outgrowing rather than outwitting. The demons become increasingly complex—Hiranayaksha is violent, Hiranakashipu is cunning and Bali is good but fails to see the big picture. Each one forces Vishnu to change, adapt and evolve. There is no standard approach, each approach is customized as per the context determined by the other. At all times, Vishnu's intention does not change.

Narsi knew that some problems could only be solved by force. So he hired a security firm known for strong-arm tactics. He also had a team of powerful lawyers because he knew many problems could be prevented by watertight contracts and fear of litigation. When the head of his marketing department was being too impudent, Narsi decided to change the proportions of the business relationship. He appointed a senior group marketing head to oversee the marketing operations of all his businesses. Suddenly, the marketing head, once a big fish in a small pond, found that he had become the small fish in a big pond, and stopped being an upstart and creating too much trouble. Some people think Narsi has multiple-personality disorder. Sometimes he gives people complete freedom. Sometimes he controls every aspect of the project. Sometimes he is kind and understanding. Sometime he shouts and screams. Narsi told his nephew, Vishal, that he changes his management style depending on the situation and the person in front of him. "Some situations demand creativity and others demand control. Some people need to be instructed while others can be inspired. We need to change as per the situation and the people around us in order to succeed." Narsi is Vishnu who knows every context is a yuga and every yuga has its own appropriate avatar.