Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management (37 page)

Read Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management Online

Authors: Devdutt Pattanaik

We dislike those who are indifferent to rules

Sati was the daughter of Daksha Prajapati, the supreme patron of the yagna. When she met Shiva, she asked him, "Where is your home?" "Home? What does that mean?" he said. "Where do you stay when it gets very hot?" "Atop Mount Kailas," he replied. "Where do you stay when it gets very cold?" "In a crematorium, next to funeral pyres that are always burning," he said. "Where do you stay when it rains?" "In a cave," he said, "or even above the clouds!"

Sati laughed as she realized he did not understand the meaning of a home. She called him Bholenath, the innocent one, and fell in love with him. She even decided to marry him, to which her father agreed with great reluctance.

At the wedding, sons-in-law are supposed to bow to their fathers-in-law. When Shiva refused to do so, Sati's father Daksha took this as a great insult. At the feast that followed, Shiva fed his companions, ghosts and dogs, with his own hands. Daksha considered these creatures foul and inauspicious. His protests made no sense to Shiva.

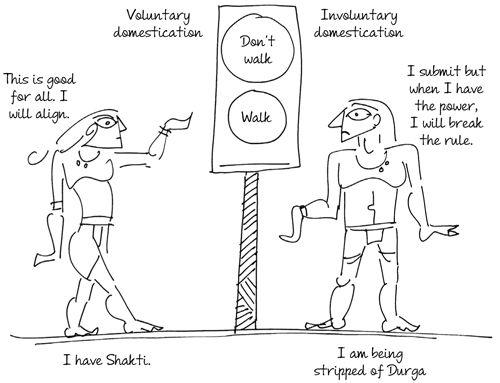

Sati realized that Shiva had no mental image of himself, and so had no need for a social body. He was indifferent to property as well as rules that are needed to endorse and affirm one's self-image. Daksha, on the other hand, saw Shiva very differently. He saw him as the destroyer, a threat to social order. Shiva was comfortable with prakriti as Kali—wild and untamed, unbound by any rules. Daksha insisted on looking upon prakriti as Gauri, bound by his rules, under his control.

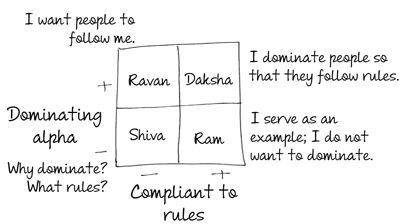

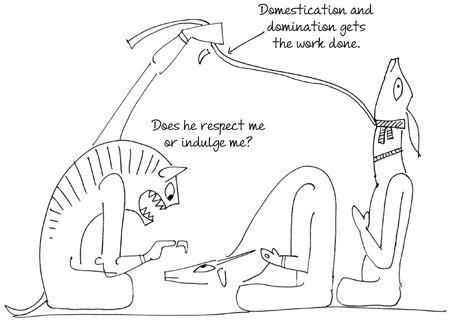

Daksha insists on rules being followed for the larger good. He demands domestication. But in enforcing the rules, his self-image gets inflated and he starts behaving as the dominant alpha. So much so that he starts seeing Shiva as an adversary, and not as one who cannot be domesticated.

Shiva is a bull. If a bull is castrated, it turns into an ox, a beast of burden. It can no longer impregnate a cow. It is important to allow Shiva to stay outside the purview of rules. Daksha fails to realize this and takes Shiva's intransigence as a personal insult. At no point is Shiva defying Daksha; he is just being himself.

Ravan, king of Lanka, defies the rules, and Ram, prince of Ayodhya, follows them, but Ravan is no Shiva and Ram is no Daksha. Unlike Shiva, Ravan wants to control people; he defies authority because he wants to be authority. Shiva is a hermit with no desire to dominate or domesticate anyone. Unlike Daksha, Ram does not want to control people; he respects the rules, not authority. He knows the value of rules and their place in life. He also knows the price one pays to uphold the rules. Thus, he is quite comfortable sacrificing personal happiness in the process of upholding the law.

Mirchandani demands that every member of his accounting firm come to office on time. They lose half-a-day of salary if they are even a minute late, but Mirchandani always comes in late. He believes that as the owner it is his privilege and he rationalizes it by saying he works late into the night unlike other staff members who leave at 6 p.m. sharp. By this, he establishes his domination in the organizational hierarchy like Ravan. Vishal, a senior accountant, just cannot come to office on time. He likes starting work only by 11 a.m., and he does not mind staying back late till all the work is done. Cutting his salary, admonishing him, has had no effect on Vishal. Mirchandani calls him arrogant and insubordinate but Vishal has no desire to defy the system. He simply functions best later in the day and finds it very difficult to wake up early. The tension between Vishal and Mirchandani reaches a point where Vishal is asked to leave. Mirchandani loses a talented worker because, like Daksha, he is more interested in Vishal's obedience and adherence to rules than in Vishal's intelligence.

Rules can be oppressive

Ram's obsession with rules dehumanizes him and makes him detached and dispassionate. The structure he creates does not benefit all: certainly not Shambuka and Sita.

The rules state that only members of the priestly professions can renounce society and become tapasvis, not members of servant professions. So when Shambuka, a servant, becomes a tapsavi, Ram beheads him.

The rules state that the king shall not have a woman who is the subject of gossip as his queen. The abduction of Sita and her stay in Ravan's palace is the subject of gossip and so Ram abandons Sita in the forest when she is heavy with child despite knowing that she has never been unfaithful in letter or spirit.

Often in organizations, people are told to leave jobs on grounds that they have broken a rule. Even though the leader has the power to forgive or overlook such transgressions he does not, for fear of the repercussions to the company as a whole. Forgiveness may be seen as a favour. It may bring ethics into question.

The rules were very clear that bonuses had to be paid as per the bell curve. Some would get more than others, and at least one person would be denied a bonus. Uday argued that all his team members had done satisfactory work and no one person's work stood out as spectacular. Those upstream did not care: the rule had to be applied every time. The team had to be graded differently. No exceptions could be made. Uday felt disgust but he could do nothing about it. Shambuka had to be beheaded and Sita had to be exiled, if he wished to be Ram.

Rules create underdogs and outsiders

In the Mahabharat, there are three great archers: Arjun, Karna and Eklavya.

Rules state that as a member of the royal family, Arjun has the right to hold the bow. The same right is not given to Karna and Eklavya because Karna belongs to a family of charioteers who are servants, while Eklavya is a tribal who lives in the forest. Karna has to learn secretly, denying his identity to his teacher. Eklavya has to learn on his own as the royal tutor, Drona, refuses to teach him. The social structure of the land is anything but fair.

Rules that are meant to subvert the law of the jungle end up creating a culture that is unfair and oppressive. Hence, the god in Hinduism is not just a rule-follower like Ram but also a rule-breaker as in the instance of Krishna. Krishna is leela purushottam who is best at playing games. He is always visualized as a cowherd and charioteer, members of the servant class, even though he is born into a royal family. He seems to be mocking social status.

The point is not the rules, or the following or breaking of them, but the reason behind the rules. Are they helping the helpless as they are supposed to, or are they simply granting more power to the powerful? Rules were created to keep the jungle out of society but more often than not they become tools to make society worse than any jungle.

Mathias knows that because he is the eldest son of the family, his taking over as CEO of his departmental store will always be seen as a function of his bloodline rather than a result of his talent. No matter how hard he works, no matter what his performance is when compared with other professionals in the company, he will always be his father's son. He is the modern-day Arjun, found in almost every family business. In contrast, Mathur knows that despite years of proving himself, he will never become the CEO; he is not part of the family bloodline and the family will never give the mantle to a professional. He is our modern-day Karna, who leaves the family business and joins a professional company, only to realize that even a multinational company has a glass ceiling. He is not an alumnus of any known business-school hence he will never be good enough. He will always be the outsider. Bakshi works as a manager in the very same departmental store. He would have been a part of the strategic team but he will never be, because he is not a business-school graduate either. No school accepted him because in the group discussions he would only express himself in Hindi. His thoughts were outstanding but those who judged him heard only his language and felt he would not fit in because he did not know English. Bakshi did not learn English since the government schools he studied in taught only the local language, because the political parties insisted on supporting the regional language over a 'foreign' language, never mind the fact that the children of these very politicians went to English-medium schools. Bakshi is the modern-day Eklavya; not quite sure why well-meaning politicians and well-meaning academicians denied him his thumb.

Rules create mimics and pretenders

In the Mahabharat, Duryodhan breaks no rules. He simply invites Yudhishtir to play a game of dice for a wager. It is Yudhishtir who gambles away his kingdom and his wife, not Duryodhan. When Draupadi, the common wife of the Pandavs, is dragged by the hair from the inner chambers to the royal court, humiliated and publicly disrobed, no one comes to her rescue, neither Bhisma, Drona, nor Karna, even though she begs them for help. Rules and laws are quoted to justify her treatment.

Later, when the Pandavs return from their thirteen-year exile in the forest, Duryodhan refuses to return their lands. He argues that according to his calendar, the Pandavs were seen before the end of the thirteenth year and so as per the agreement, they have to return to the forest for another thirteen years. Krishna offers the counter-argument that the Kaurav calendar does not take into account the concept of leap years. In fact, the Pandavs have lived in exile longer than stipulated. Duryodhan disagrees with this. So Krishna offers a compromise, "Just give five villages to the five brothers for the sake of peace." Thus cornered, Duryodhan reveals the true intention behind his pretence of rational arguments and says, "I will not give them a needle point of land under any circumstances."

Duryodhan is the pretender, the mimic, who follows the rules but does not care for the purpose they serve. He uses rules to control the world around him and get his way.

In a world where processes and systems matter more than feelings, it is clear that the overwhelming culture promotes Duryodhans. We assume that the obedient person is the committed person. Yet, we can sense that the team is disconnected and detached emotionally. They become professional because they have stopped caring about people; all they care about is tasks and targets and go about accomplishing these ruthlessly and heartlessly. In fact, when we celebrate professionalism, we celebrate Duryodhan who values the letter of the law, not the spirit. Behaviour can be proven and measured, not belief.