Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management (18 page)

Read Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management Online

Authors: Devdutt Pattanaik

A yajaman has the power to take and give life

The sage Vishwamitra storms into the kingdom of Ayodhya and demands that the crown prince Ram accompany him to the forest and defend his hermitage from rakshasas. King Dashrath offers his army instead, as he feels Ram is too young, but Vishwamitra insists on taking Ram. With great reluctance, Dashrath lets Ram go.

In the forest, Vishwamitra points to Tataka, the female leader of the rakshasas, and asks that she be killed. When Ram hesitates because he has been taught never to raise his hand against a woman, Vishwamitra argues that a criminal has no gender. Ram accordingly raises his bow and shoots Tataka dead.

Later, Vishwamitra shows Ram a stone that was once Ahalya, the wife of Gautama, cursed to become so after her husband caught her in an intimate embrace with Indra. Vishwamitra asks Ram to step on the stone and liberate the adulteress. When Ram hesitates because he has been taught the rules of marriage should always be respected, Vishwamitra argues that forgiveness is as much a part of marriage as fidelity. Ram accordingly places his feet on the stone and sets Ahalya free from her curse.

Ram, well-versed in theory, is thus given practical lessons about being a yajaman: he will be asked to take life as well as give life. At times, he will be expected to be ruthless. At other times, he will be expected to be kind.

In business, the yajaman has the power to give a person a livelihood, grant him a promotion, sideline him or even fire him. These decisions have a huge impact on the lives of the devatas who depend on the business.

One day, Jake is asked by his boss to fire an incompetent employee. While the reasons are justified, Jake finds it the toughest thing to do. He has several nights of anxiety before he can actually do it. Then, a few weeks later, Jake is asked to mentor a junior employee who has been rejected by the head of another department. This is even tougher as the junior employee is rude and lazy and impossible to work with. Jake struggles and finally succeeds in getting work done through the junior employee. Jake does not realize it but his boss is being a Vishwamitra mentoring a future king.

The size of the contribution does not matter

To rescue Sita, Ram raises an army of animals and gets them to build a bridge across the sea to the island-kingdom of Lanka where Sita is being held captive by the rakshasa-king Ravan.

Vultures survey the location. Bears serve as the architects. Monkeys work on implementing the construction, carrying huge boulders and throwing them into the sea. The work is tedious. The monkeys are jumping and screeching everywhere to ensure everything is being done efficiently and effectively. Suddenly, there appears amongst them a tiny squirrel carrying a pebble.

This little creature also wants to contribute to the bridge-building exercise. The monkeys who see him laugh. One even shoves the squirrel aside considering him an overenthusiastic nuisance.

But when Ram glances at the squirrel, he is overwhelmed with gratitude. He thanks the tiny creature for his immense contribution. He brushes his fingers over the squirrel's back to comfort him, giving rise to the stripes that can be seen even today, a sign of Ram's acknowledgment of his contribution.

In terms of proportion, the squirrel's contribution to the bridge is insignificant. But it is the squirrel's 100 per cent. The squirrel is under no obligation to help Ram, but he does, proactively, responsibly, expecting nothing in return. Ram values the squirrel not for his percentage of contribution to the overall project but because he recognizes a yajaman. A squirrel today, can be a Ram tomorrow.

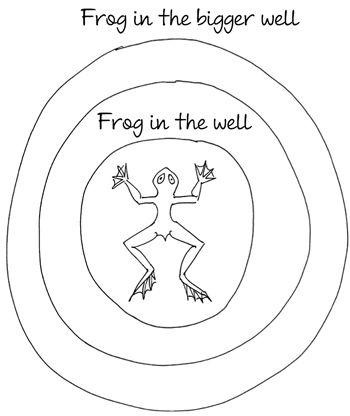

Proportions or matra play a key role in Indian philosophy. The scale of a problem has nothing to with the potential of the decision-maker. A kupamanduka, or frog in a well, and a chakravarti, or emperor of the world, are no different from each other, except in terms of scale. Both their visions are limited by the frontier of the land they live in. In case of the frog, it is the wall of the well. In case of the king, it is the borders of his kingdom. Both can be, in their respective contexts, generous or prejudiced. To expand scale, both have to rise.

Whenever Mr. Lal goes to his factory, he makes sure he speaks to people at all levels, from workers to supervisors to managers to accountants to security people. He is not interested in finding out who did the job well or who did not. That, he feels, is the job of managers. He is only interested in identifying people in the factory who take proactive steps to solve a problem. He consciously seeks decision-makers, like the executive who prepared a report on waste management without being asked to, or the supervisor who voluntarily motivated his team to clean the toilets when the housekeeping staff went on strike. For Mr. Lal these 'squirrels' who take responsibility are talents to be nurtured.

All calls are subjective

The

Kathasaritsagar

tells the story of a sorcerer who requests Vikramaditya, king of Ujjain, to fetch him a vetal or ghost that hangs upside down like a bat from a tree standing in the middle of a crematorium. "Make sure you do not talk to the vetal; if you speak, he will slip away from your grasp," warns the sorcerer.

Vikramaditya enters the crematorium, finds the tree, and the vetal hanging upside down from its branches. He catches the ghost, pulls it down and begins make his way back to the city when the ghost starts chatting with him, telling him all kinds of things, annoying him, yelling into his years, cursing him, praising him, anything to make him speak but Vikramaditya refuses to succumb to these tricks.

Finally, the vetal tells Vikramaditya a story (a case study?), and at the end of it asks the king a question. "If you answer this question, then you are indeed Vikramaditya, a king, a yajaman who thinks and takes decisions. But if you stay quiet, and simply follow orders, you are no Vikramaditya. You are a pretender, a mere karya-karta, who simply follows orders."

Vikramaditya cannot bear being called a pretender or a karya-karta. So he speaks and answers the question with a brilliant answer. The vetal gasps in admiration.

However, almost immediately after that the wily ghost slips away, cackling without pause and goes back to hanging upside down from the tree in the crematorium.

The next night, Vikramaditya walks back to the tree and once again pulls the vetal down. The vetal tells him another story with a question at the end. Once again the vetal tells the king, "If you are indeed the wise Vikramaditya, as you claim to be, you should be able to judge this case. So answer my question. And if you choose to stay silent, I am free to assume I have been caught by a commoner, a pretender, a mimic!" Once again the proud king gives the answer to which the vetal gasps in admiration. And once again he slips away with a cackle.

This happens twenty-four times. The twenty-fifth time, a tired and exasperated Vikramaditya, sighs in relief. He has succeeded.

"Have you really?" asks the vetal, "How do you know the answers you gave the previous times were right? All answers are right or wrong only in hindsight. You made decisions because you thought they were right. The answer would have been subjective this time, too. Only now, you are not sure of the answer, you hesitate, and so remain silent. This silence will cost you dear. You will succeed in taking me to the sorcerer who will use his magic to make me his genie and do his bidding. His first order for me will be to kill you. So you see, Vikramaditya, as long as you were karta, taking calls, you were doing yourself a favour. As soon as you stop making your own decisions, stop being a karta, you are at the mercy of others and you are sure to end up dead."

Everyone looks at the karta for a decision despite data being unreliable, the future being uncertain, and outcomes that are unpredictable. Not everyone can do it. He who is able to make decisions independently is the karta. He who allows others to do so is the yajaman.

The investors are chasing Deepak. He built an online coaching class of engineering students that was bought by a large educational portal for a phenomenal amount. Now the investors expect Deepak to repeat this success. Deepak is filled with self-doubt. He is not sure what it was about the website he built that made it so valuable in the eyes of the buyers. Was it just luck? Since he does not know what made him successful, how can he repeat the success. There was nothing objective about his creation. Must he follow his gut instincts again? But the investors will not allow him to do so; their auditors will keep asking him for explanations and reasons, assuming his calls are rational. And the media, which celebrated the sale, is watching his every move continuously. He is a victim of success. How he wishes he never became an entrepreneur. How he wishes he could roll back the clock, be a simple engineer working in a factory, diligently doing what the boss tells him to do.

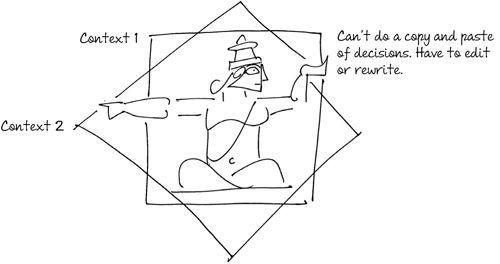

All decisions are contextual

Amongst the twenty-five stories that the vetal told Vikramaditya, this is one: a king killed a merchant and laid claim to all his property. The merchant's widow fled the kingdom swearing revenge. She seduced a priest and was impregnated by him. She abandoned the son thus born at the door of a childless king who adopted the foundling and raised him as his own. "Who is the father of this child: the merchant who was married to his mother, the priest who made his mother pregnant or the king who adopted him?"

Vikramaditya replies with the caveat that the answer would depend on the culture to which the king belongs. In some cultures only biological fathers matter, in some, legal fathers matter and in others, foster fathers matter more. There is no objective answer in matters related to humans.

In the Mahabharat, Pandu is called the father of the Pandavs even though he is not their actual biological father. The law of the land states that a man is the father of his wife's children. The Pandavs demand a share of Pandu's kingdom on the basis of this law. Is this law the right law? At Kurukshetra, the Pandavs kill Bhisma, the man who raised them as a foster father would, because he fights on the opposing side. Is that ethical? In the Ramayan, Ram is celebrated for being faithful to one wife, yet in the Mahabharat, men have many wives and the Pandavs even share a common wife. What is appropriate conduct?

Laws by their very nature are arbitrary and depend on context. What one community considers fair, another may not consider to be fair. What is considered fair by one generation is not considered fair by the next. Rules always change in times of war and in times of peace, as they do in times of fortune and misfortune.

Thus, no decision is right or wrong. Decisions can be beneficial or harmful, in the short-term or long-term, to oneself or to others. Essentially, every decision has a consequence, no matter which rule is upheld and which one is ignored. This law of consequence is known as karma.

Mr. Gupta has to choose a successor. Should it be his eldest son who is not very shrewd? Should it be the second son who is smart but not interested in the business? Must it be his daughter, who feels gender should not be a criterion, but who fails to realize she is not really that smart? Should it be his brilliant son-in-law, who does not belong to the community which will annoy a lot of shareholders? Must the decision be based on emotion, equality, fairness, loyalty, or the growth of the business and shareholder value? Each and every answer will have opponents. Must he simply divide the business before he dies for the sake of peace or let his two sons and daughter fight it out in court after his death? There is no right answer, he realizes. Traditionally, in the community, the eldest son inherited everything. That was convenient but often disastrous. Mr. Gupta does not want to impress the community; he wants his legacy to outlive him. He also wants all his children to be happy. His desires impact the decision as much as the context.