Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management (20 page)

Read Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management Online

Authors: Devdutt Pattanaik

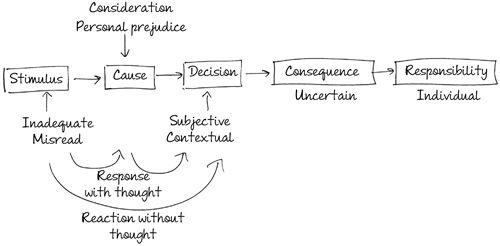

If the decision is bad, the yajaman alone is responsible

A sage once asks a thief, "Why are you stealing?"

The thief replies, "I am poor. I need to feed my family. There is no other employment. I am desperate."

"Will your family bear the burden of your crime?"

"Of course, they will," Suddenly, not so sure of his own response, the thief decides to check. He asks his wife and son if they would bear the burden of his crimes and they reply, "Why? It is your duty to feed us. How you feed us is your problem not ours."

The thief feels shattered and alone. The sage then tells the thief, who is Valmiki, the story of Ram, as told in the Ramayan and compares and constrasts it with the story of the Pandavs from the Mahabharat.

Ram is exiled from Ayodhya for no fault of his, following the palace intrigues of his stepmother Kaikeyi. In the Mahabharat, the five Pandav brothers are exiled because they gamble away their kingdom, Indraprastha. In the Ramayan, Ram's exile lasts fourteen years. In the Mahabharat, it is an exile of thirteen years. In the Ramayan, there is no guarantee that at the end of the exile, Ram will be crowned king. In the Mahabharat, however, the Kauravs promise to return the Pandav lands on completion of the latter's exile.

While it is his father's request that he go to the forest, it is ultimately Ram's decision whether to obey his father or not. He decides to obey. He is no karya-karta to his father. He is a yajaman. He is never shown complaining or blaming Kaikeyi but is rather visualized as being stoic and calm throughout. In contrast, the Pandavs blame the Kauravs and their uncle Shakuni and are visualized as angry and miserable, even though they agree to the terms of their exile. They are compelled to obey the rules. Yudhishtir cannot bear the burden of being a yajaman, and agrees to play a game of dice, which costs him his kingdom, while his brothers assume the role of reluctant karya-kartas.

For Ram, Kaikeyi is no villain; he is no victim and certainly not a hero. A hero is provoked into action. A yajaman needs no provocation to act. Provocation makes action a reaction, turns a yajaman into a devata and a karta into a karya-karta. A yajaman takes his own decision. Ram has chosen to accept his exile. He could have defied the wishes of his father, and taken control of the throne, but he chose to obey. He takes ownership of his exile. The Pandavs constantly see their exile as an unfair punishment, a burden they are forced to bear. Perhaps that is why Ram (and not the Pandavs) is enshrined in temples.

A yajaman is one who does not blame anyone for any situation. He knows that his fortune and misfortune are dependent on many forces. Besides his knowledge, skills, experience and his power of anticipation, a lot depends on the talent of people around him—the market conditions and regulatory environment. He simply takes charge of whatever situation he is in, focusing on what he can do, never letting the anxiety of failure pull him back, or the confidence of success make him smug.

Upon the completion of their course in college, there is placement week. Jaideep gets two offers: one from an investment banking firm in New York and one from a leading trading firm in India. Jaideep chooses the job in New York, but the moment he lands there, news of recession fills Wall Street. Companies are forced to shut down or downsize. Jaideep finds himself without a job. As he flies back to Mumbai, he is angry and anxious. But he keeps reminding himself: it is his decision; no one forced him into the choice he made. He realizes that being a yajaman is tough.

If the decision is good, the yajaman is the beneficiary

There is a king called Indradyumna, who after death goes to paradise to enjoy the rewards of his good deeds on earth. But, one day, he is told by the gods to leave paradise. He can come back only if he finds at least one person on earth who recounts his great deeds.

When Indradyumna reaches earth, he realizes that centuries have passed since his reign. The trees are different, the people are different, even his kingdom looks different. The city and temple he built no longer stand. No one remembers him. He visits the oldest man on earth, and goes to the oldest bird, but neither of them recall him. Finally, he goes to the tortoise, who is older than the oldest man and the oldest bird and the tortoise says he remembers Indradyumna because his grandfather had told him that a king called Indradyumna built the lake he was born in. Indradyumna, however, does not remember ever building a lake.

The tortoise explains, "You distributed many cows in charity during your lifetime, hoping to win a place in paradise, which you did. As the cows left the royal cowshed, they kicked up so much dust they created a depression which collected water and turned into a lake, becoming the home of many birds and, fishes, worms and, finally, the home of my grandfather."

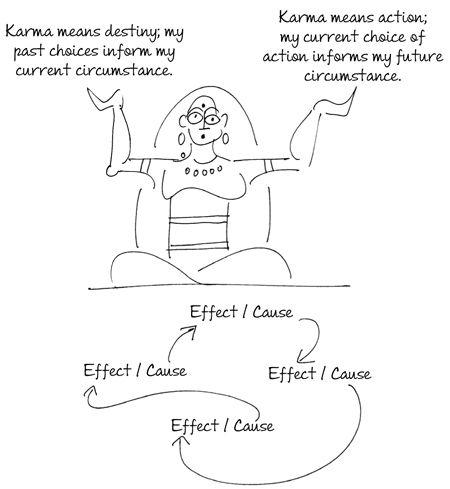

Indradyumna is pleased to hear what the tortoise has to say. So are the gods who welcome Indradyumna back to paradise. As Indradyumna rises to heaven, the irony does not escape him: he is remembered on earth for a lake that was unconsciously created, and not for the cows that were consciously given. He benefits not from his decisions but from the unknown consequences of his decisions.

Making decisions is not all gloom. It also yields positive results, sometimes even unexpected windfalls. Just as the yajaman is responsible for negative consequences, he has a right over positive consequences. It is this hope of unexpected positive consequences that often drives a yajaman.

Harish-saheb's factory provided a livelihood to Suresh who was able to give a decent education to his two sons, one of whom went on to become a doctor. Suresh was always grateful to Harish-saheb because before the factory was set up in the small town where he lived, he had been unemployed for over a year. When his son builds a hospital, Suresh insists that it be named after that 'giver of cows'—Harish-saheb. The Harish Nursing Home that serves the local community is, in this allegory, Indradyumna's lake. Harish-saheb's factory is long gone, replaced by a shopping mall.

Violence

Without violence, there is no nourishment. Unless the mineral is consumed, the plant cannot grow. Unless the plant is consumed, the animal cannot grow. Physical growth demands the consumption of another. Only mental growth is possible without consuming another; but it is a choice humans rarely make.

Business is violent

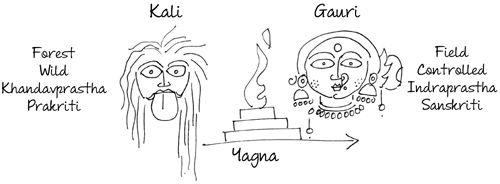

In the Mahabharat, the Pandav brothers inherit a forest, Khandavprastha, and want to build on it a great city, named Indraprastha, the city of Indra. So Krishna says, "Burn the forest. Set aflame every plant, every animal, every bird and every bee." When the Pandavs express their horror at the suggestion, Krishna says, "Then do not dream of a city."

Humans have the choice of outgrowing hunger like Shiva, or indulging hunger like Brahma. When we choose the latter, forests have to be cleared to make way for fields, and mountains have to be bored into to get to the minerals. The bull has to be castrated and turned into an ox, to serve as a beast of burden. The spirit of the wild horse has to be broken if it has to be ridden. Each of these actions has a consequence. This is violence and like all actions, even violence has consequences.

Culture is essentially domesticated nature. Different groups of humans have domesticated nature differently.

In Hindu mythology, the wild, naked and bloodthirsty goddess Kali and the gentle, demure and domestic goddess Gauri are one and the same. The former embodies the forest. The latter embodies the field. The former embodies prakriti. The latter embodies sanskriti. In between stands Brahma, performing the yagna that tames the wild and lays down the rules of man. Kali is the mother who existed before Brahma and his yagna. Gauri is the daughter, a consequence of Brahma's desire, forged by his yagna. Kali creates Brahma; Brahma creates and controls Gauri. He wants her to be obedient.

Humans have been constantly finding new and innovative ways of controlling nature. First it was the agricultural revolution. Then it was the industrial revolution. All these are violent attempts to gain more and more resources to satisfy the ever-increasing demands of humanity.

With each economic revolution, something has been sacrificed. The agricultural revolution had a negative impact on the lives of tribals who lived in forests and nomads who wandered freely over land. The industrial revolution displaced farmers, made them landless workers in factories and cities. The knowledge revolution means that jobs are being outsourced to foreign lands, benefitting the rich in the homeland, at the cost of the poor.

Violence is an intrinsic part of nature. In nature, animals kill plants and animals in order to survive. Animals compete with each other to survive. Humans have the ability to create a culture that can survive and thrive without needing to kill or compete. But this is not the path that is taken. Using force and fire, we tame nature. We expect Kali to turn into Gauri without resistance, but when she demands that Brahma turn into Vishnu, we mock her. In other words, we want to change the outer world (nature and society) rather than the inner world (mind). So long as we are not the victims of violence, we do not mind being the perpetrators of that violence. This is the human condition.

When Raymond bought a house in the suburbs ten years ago, he had a clear view of the sea and the mountains. But today his view is blocked by huge buildings, malls, roads and office complexes. He hates it. But then his wife pointed out, "Before our housing society was built I am sure there was a beautiful meadow here full of birds and butterflies. Someone would have been upset that a house was built here. But thanks to that decision by the builder, you and I have a home. Are you willing to sacrifice your house for the environment? Just as you wanted a house, other people also want a house and a job and so for them new houses, offices and roads have to be built. As long as society wants development, we have to be willing to sacrifice the environment. Everything has a price."

Violence is not always apparent

Manu gives a tiny fish shelter in his pot, determined to save it from the big fish. As the days pass, the fish in Manu's pot keeps growing bigger and so Manu builds bigger pots to accommodate it. A point comes when the fish is so big that it has to be put in a pond, then a lake, then a river, and finally, the sea. The fish keeps growing and so to expand the sea, Manu asks the rain to fall. The rising sea causes flooding. The earth starts getting submerged beneath the waters. This is Pralay, the end of culture, the end of humanity, the end of all organic life.

Manu does not see the inherent violence in the creation of the pot. By saving the small fish he was denying the big fish their food. Another small fish was killed in place of the one rescued. The small fish does not stay small forever. It keeps growing. By seeking resources to provide for the ever-growing fish, he was destroying nature. At no point does Manu think the big fish can fend for itself. In trying to expand the pot to satisfy the demands of the fish, Manu ends up destroying the world.