Read Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management Online

Authors: Devdutt Pattanaik

Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management (21 page)

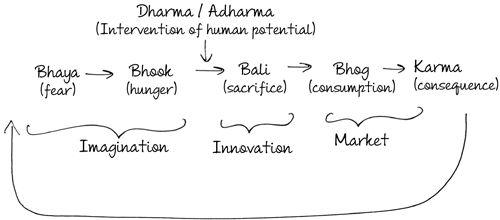

Human society is built on the principle that the strong shall provide for the weak. The alternative is called jungle law and frowned upon. We also speak in terms of permanence: no aging but eternal existence, a growth curve that never wanes. The alternative is called being defeatist and philosophical. But in trying to provide everything for everyone, all the time, much is destroyed: cultures are destroyed, more of nature is destroyed, often for the noblest of intentions.

When the factory was built, the government insisted that schools and jobs be created to support the local tribal community. The factory owners did so diligently. Members of the tribal community were encouraged to study and learn new skills. They got menial jobs and they encouraged their children to study harder so that they could get more senior positions. Two generations down the line, the old tribal ways have been all forgotten. The stories are no longer told. The rituals are no longer practiced. A whole way of life has ceased to exist. Only anthropologists and museums have any memory of it. But the factory does not see itself as the destroyer of a culture; it simply sees itself as the harbinger of economic growth.

Mental violence is also violence

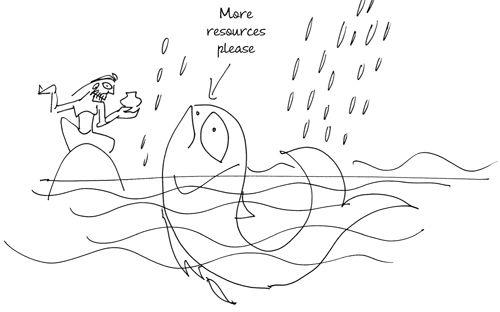

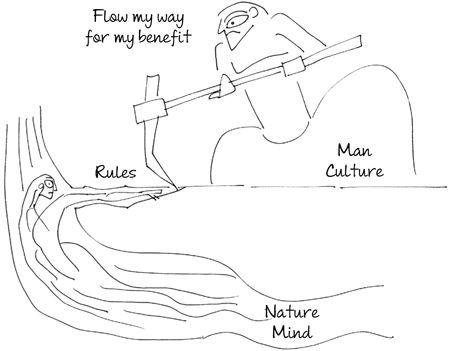

The Bhagavat Puran tells the story of the river Yamuna that flowed past Vrindavan, the forest that was the favourite haunt of Krishna and his companions. One day, Krishna's elder brother, wanted to take a bath and he asked Yamuna to come to him. Yamuna said, "But I cannot break the riverbanks. You must come to me." Balaram did not heed her words. He simply swung his plough and hooked it on the riverbank and dragged Yamuna, by the hair, to come towards him.

This story can be seen as a metaphor for canal irrigation. Unless the riverbank is broken, water cannot be made to flow into the fields. Violence helps man reorganize nature to his benefit. This is saguna violence, violence that can be seen. Violence associated with agriculture, industrialization and development is visible violence.

This story can also be seen as a metaphor for domesticating the mind. Our imagination flows in different ways as determined by our whim. Society, however, demands we control our imagination and function in a particular way, guided by rituals and rules. This is also violence: mental violence or nirguna violence, violence that cannot be seen. Every human wants to live by his rules but laws, values, systems, processes, regulations compel them to live by organizational rules. This results in invisible violence. Through mental violence, the human-animal is compelled to behave in a civilized way. At first there is resistance, but later it becomes a habit.

Radhakrishna loves Sundays when he wakes up at 10 a.m. and spends the day playing with his daughters, not shaving, not bathing, eating a late lunch, ending the day watching a movie with his wife on their home theatre system. Mondays he hates, as he has to get up at 6 a.m. and drive to work to be in office by 8 a.m., following up with team members, cajoling them or compelling them to finish their tasks so that he can give a favourable report to the client located in another time zone. It is a thankless job as he has to hear complaints from everyone around. But it pays well. On Sunday, Radhakrishna's Yamuna flows as per her will. On the rest of the days, it flows along the canals dug by others.

Violence creates winners and losers

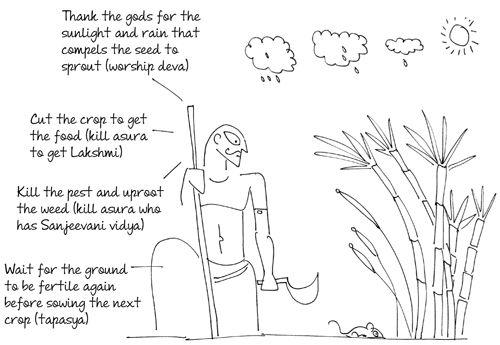

Harvest festivals are typically associated with the death of asuras: Diwali is associated with the death of Narak-asura, Onam and Diwali with the death of Bali-asura, and Dassera is associated with the death of Mahish-asura.

The Purans states that asuras live in Pa-tala, the realm under the ground. All wealth in its most elemental form, be it plant wealth or mineral wealth, exists under the earth. Asuras will not let Lakshmi leave their realm; so the devas have to use force.

The sun (Surya) and the rain (Indra) pull out plant wealth, while fire (Agni) in the furnace and wind (Vayu) through bellows melts rocks and gets metal out of ore. Activities such as farming and mining are thus described as war waged by devas against asuras. Unless the asura is killed, Lakshmi cannot be obtained.

Lakshmi is called Pulomi, daughter of the asura-king, Puloman, and Bhargavi, daughter of the asura-guru, Bhrigu. Shukra, the other asura-guru, is her brother. In victory, the daughter of the asuras ends up as Sachi, wife of Indra, showering devas with pleasure, creating paradise with her arrival.

This story of the devas defeating the asuras is a narrative acknowledgment of the violence inherent in creating wealth. It refers to the visible violence of agriculture, mining, industrialization and every other extraction process.

It also reveals that with violence, there is bound to be a winner and a loser. Someone gains from the violence, and from that comes conflict. We adore those who pull wealth towards us rather than those who push wealth away from us. For humans, devas are gods, as their activities bring forth hidden wealth while asuras are demons, as they hide wealth in their subterranean realms.

The new road connecting the two major cities was going to pass through their farms. Twenty families would be displaced. The government promised them adequate compensation. For Mita-tai, this meant the end of all the things she had grown up with. The pond would go, as would the orchard. She would have to move to a new house maybe in the city with her son. She wanted to protest, but who would listen to an old lady. They would see her as an obstacle to progress. She cursed the government and all those who would ride on the road that took away her farm. But these were hollow curses of an unknown woman. According to the collector, the land belonged not just to her but also her two sisters and four brothers. All their names were on the deed, attested by her father's thumb impression. Only she had stayed in the village, with her husband, and taken care of the farm. Suddenly, all the relatives descended to take a share of the compensation. The deed was prepared thirty years ago before anyone had migrated and before the family quarrels began. Everyone had forgotten about the deed, until now. The government refused to pay any money until a consensus was reached. It took two years for that to happen. Mita-tai got only a fraction of what she felt she deserved. She went to her son's house, heartbroken. She died soon after. The road connecting the two cities brought livelihood to thousands of families. Indra had won his Sachi.

Violence is culturally unacceptable if taking is not accompanied by giving

King Harishchandra had once promised to sacrifice his son, Rohit, if the gods cured him of a terrible ailment. The gods kept their end of the bargain, but Harishchandra hesitated about keeping his. He sought a way out, so his courtiers suggested he adopt a son. "The gods will not mind so long as you sacrifice a son," they said. So the king offered a reward of a hundred cows in exchange for a son he could adopt.

No one offered their sons; even orphans were not willing to be adopted, as they knew what was in store for them. But one priest, by the name of Ajigarta, agreed to sell his son, for he was very poor and he had three sons. "The eldest is dear to me. The youngest is dear to my wife. The middle one, we can spare." And so, the king adopted Ajigarta's middle son, whose name was Sunahshepa.

The time came to sacrifice Sunahshepa, but the royal priests refused to carry out the sacrifice of a human being. No one was willing to commit such a heinous act. "I will do it," said the boy's father, "if I am given another hundred cows."

This story fills us with horror, as the yajaman does not behave as a yajaman ought to. Rather than taking care of his subject, the king wants to sacrifice him for his own benefit. Rather than taking care of his son, the father wants to sell him for his own benefit. Both king and father are thinking only of their hunger. Both are indifferent to the needs of Sunahshepa.

In nature, it is acceptable that animals think only about themselves. But in culture, such selfishness is condemned.

We demand a fair exchange from people who have more wealth and more power. Unfortunately, those who have more wealth and power are often in those positions because they have denied others any share of wealth and power. This is the root cause of rage and revolution. But things get complicated in defining what is fair. Is it fair for a king to kill another man's son to save his own? Is it fair for a father to sell one child to feed the others? Animals do not resent the predator who catches the prey, but humans do resent humans who exploit other humans.

The story of Sunahshepa draws attention to greed too. Ajigarta can plead poverty when he sells his son. But when the king offers to sacrifice his son, his motivation is not poverty anymore. What is acceptable when we are poor is not acceptable when we are not hungry. But then who decides who is poor and who is not. Certainly not a king who changes the definition of who his son is depending on convenience.

When Kanta could not pay back her dues, she gave her son Raghu away to a man called Pal who, in exchange, cleared her loan with the local moneylender. Raghu would work at Pal's house and be provided with food and shelter, but no salary. That was all right as Kanta could barely feed her six children. For Pal, transactions such as this enabled him to get labour at so low a cost that he was able to offer goods at prices that interested many foreign buyers. Kanta and Raghu are not even aware that there are laws against bonded labour and child labour. They are simply trying to survive, and Pal is taking advantage of the situation. Raghu, like Sunahshepa, lies in the twilight zone where neither parent nor state are able to take care of him.

Violence becomes culturally acceptable when we take because no one gives

Indra, king of devas, once forbade the sage, Dadichi, from sharing the secret of the yagna with anyone. "If you do reveal the secret, your head will burst into a thousand pieces." But the twin sons of Surya, the Ashwini, were eager to learn this secret. When informed about the curse, the twins found a way out.

The Ashwini used their knowledge of medicine to cut off the head of Dadichi and replace it with a horse's head. Through the horse's head, Dadichi revealed the secret of the yagna. As soon as the revelation was complete, the horse head burst into a thousand pieces thus fulfilling Indra's curse. The Ashwini twins then attached the sage's original head and Dadichi came back to life.