Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management (9 page)

Read Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management Online

Authors: Devdutt Pattanaik

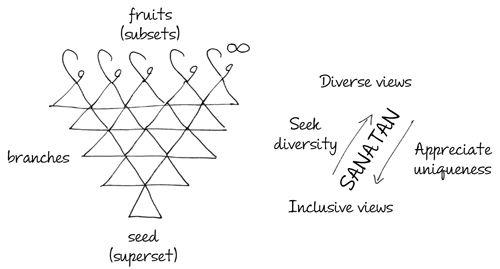

With diversity came arguments, but these were not born out of scepticism but out of faith. The argumentative Indian did not want to win an argument, or reach a consensus; he kept seeing alternatives and possibilities. The wise amongst them sought to clarify thoughts, understand why other gods, who also contained the spark of divinity, did not see the world the same way. The root of the difference was always traced to a different belief that shaped a different view of the world in the mind.

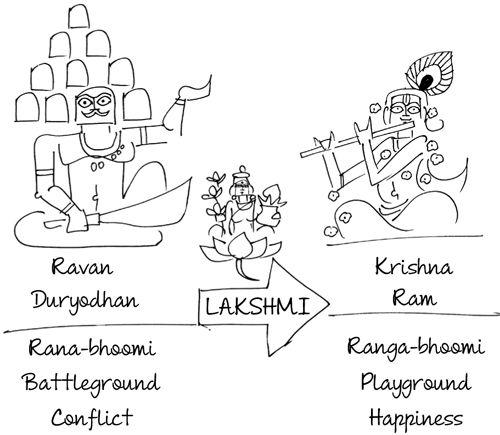

As one goes through the epics of India one notices there are rule-following heroes (Ram) as well as rule-following villains (Duryodhan), rule-breaking heroes (Krishna) as well as rule-breaking villains (Ravan). Thus, goodness or righteousness has nothing to do with rules; they are at best functional, depending on the context they can be upheld or broken. What matters is the reason why rules are being followed or broken. This explains why Indians do not value rules and systems in their own country as much as their counterparts in Singapore or Switzerland, but they do adhere to rules and systems when they go abroad.

Between 2002 and 2012, international observers noticed that when cases of fraud and corruption were raised in the UK and US, they were dealt with severely and a decision was arrived at in a short span of time. During the same period, the Indian legal system pulled up many Indian politicians, bureaucrats and industrialists for similar charges. Their cases are still pending, moving from one court to another. The Indian legal system is primarily equipped only to catch rule-breaking Ravans, not rule-upholding Duryodhans.

That Ram and Krishna (avatars of Vishnu) are worthy of worship and Ravan and Duryodhan (sons of Brahma) are not has nothing to with behaviour. It has to do with belief. Why are they following or breaking the rule? The answer to this question is more critical than whether they are following or breaking the rule.

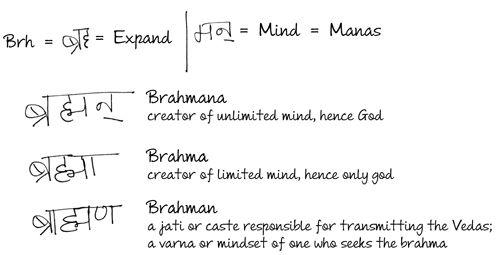

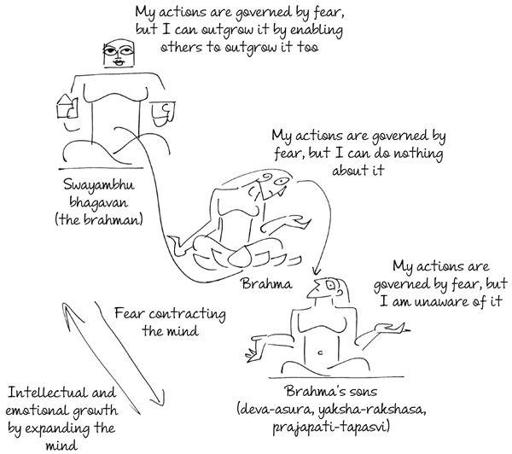

Belief is forged as imagination responds to the challenges of nature: death and change. Fear contracts the mind and wisdom expands it. From the roots brah, meaning growing or widening, and manas, meaning mind endowed with imagination, rise three very important concepts in India that sound very similar: the brahman (pronounced by laying stress on neither vowel), Brahma (pronounced by laying stress on the last vowel only) and brahmana (pronounced by laying stress on the first vowel and the last consonant).

- The brahman means an infinitely expanded mind that has outgrown fear. In early Nigamic scriptures, the brahman is but an idea that eventually becomes a formless being. By the time of the Agamic scriptures, the brahman is given form as Shiva or Vishnu. The brahman is swayambhu, meaning it is independent, self-reliant and self-contained, and not dependent on fear for its existence.

- Brahma is a character in the Agamic literature. He depends on fear for his existence. From fear comes his identity. Fear provokes him to create a subjective truth, and be territorial about it. The sons of Brahma represent mindsets born of fear: devas who enjoy wealth, asuras who fight to retrieve wealth, yakshas who hoard wealth, rakshasas who grab wealth, prajapatis who seek to enforce rules and tapasvis who seek to renounce rules. Brahma and his sons are either not worshipped or rarely worshipped, but are essential constituents of the world. They may not be Gods, but they are gods. Asuras and rakshasas started being visualized as 'evil beings' by Persian painters of the Mughal kings and being referred to as 'demons' by European translators of the epics.

- Brahmana, more commonly written as brahmin, commonly refers to the brahmana 'jati', or the community of priests who traditionally transmitted Vedic rituals and stories. It also refers to brahmana 'varna', representing a mindset that is seeking the brahman.

Ravan and Duryodhan descend from Brahma, unlike Ram and Krishna who are avatars of Vishnu; though born of mortal flesh, Ram and Krishna embody the brahman. Fear makes Ravan defy other people's rules. Fear makes Duryodhan pretend to follow rules. Both are always insecure, angry and bitter, always at war, and trapped in the wheel of rebirth, yearning for immortality. This is rana-bhoomi, the battleground of life, where everyone believes that grabbing Lakshmi, goddess of wealth, is the answer to all problems.

Ravan and Duryodhan are never dismissed or dehumanized. Effigies of Ravan may be burned in North India during Dassera celebrations and sand sculptures of Duryodhan may be smashed in Tamil Nadu during Therukuttu performances, but tales of the nobility of these villains, their charity, their past deeds that may account for their villainy still persist. The Ramayan repeatedly reminds us of how intelligent and talented Ravan is. At the end of the Mahabharat, Duryodhan is given a place in swarga or paradise. The point is not to punish the villains, or exclude them, but first to understand them and then to uplift them. They may be killed, but they will eventually be reborn, hopefully with less fear, less rage and less bitterness.

Vishnu descends (avatarana, in Sanskrit) as Ram and Krishna to do uddhar (thought upliftment), to turn god into God, to nudge the sons of Brahma towards the brahman. At no point does he seek to defeat, dominate, or domesticate. He offers them the promise of ranga-bhoomi, the playground, where one can smile even in fortune and misfortune, in the middle of a garden or the battlefield. Liberation from the fear of death and change transforms Brahma and his sons into swayambhu, self-contained, self-reliant beings like Shiva and Vishnu, who include everyone and desire to dominate no one. The swayambhu is so dependable that he serves as a beacon, attracting the frightened. Those who come to him bring Lakshmi along with them. That is why it is said Lakshmi follows Vishnu wherever he goes.

Amrit, the nectar of immortality, takes away the fear of death. The quest for amrit makes Brahma pray to Shiva and Vishnu in Hindu stories. In Buddhist stories, Brahma beseeches the Buddha to share his wisdom with the world. In Jain stories, Brahma oversees the birth of the tirthankar. Both the brahmanas and the shramanas knew that amrit is not a substance, but a timeless idea. This idea cannot be forced down anyone's throat; like a pond in the forest, it awaits the thirsty beast that will find its way to it, on its own terms, at its own pace.

The head of the people department, Murlidhar, suggested that they do personality tests to identify and nurture talent in the company. The owner of the company, Mr. Walia, did not like the idea. "The personality of people keeps changing depending on who they are dealing with, depending on what they are going through in life." Murlidhar pointed to scientific evidence that personality can be accurately mapped and how core personality never changes. "I do not believe it," said Mr. Walia. "How can you not," said Murlidhar, "It is science!" Murlidhar believes there is only one objective truth outside human imagination that science can help us discover; he does not care much for the subjective. Mr. Walia believes that everyone believes in different things, and these beliefs forged in the imagination are true to the believer, hence must be respected, no matter what objective tests reveal. Mr. Walia values perspective and context; he is more aligned to the sanatan than Murlidhar.

Indians never had to articulate their way of life to anyone else; the gymnosophist never felt the need to justify his viewpoint or proselytize it. Then, some five hundred years ago, Europeans started coming to India from across the sea, first to trade, then to convert, and eventually to exploit. What was a source of luxury goods until the seventeenth century became the land of raw materials by the nineteenth century, and a market by the twentieth century, as the industrial revolution in Europe destroyed indigenous industry and changed the world.

Indians became exposed to Western ideas for the first time as they studied in missionary schools to serve as clerks in the East India Company, the world's first corporation. Sanatan had to be suddenly defended against Western ideas, using Western language and Western templates. Indians were ill-equipped to do so. So the Europeans started articulating it themselves on their terms for their benefit, judging it with their way of life. After the eighteenth century fascination with all things Indian, Orientalists spent the nineteenth century disparaging the new colony. Every time a local tried to explain the best of their faith, the European pointed to the worst of Indian society: caste, the burning of widows, and idol worship.

Indians became increasingly defensive and apologetic, as they had to constantly match Indian ways to Western benchmarks. Attempts were even made to redefine Hinduism in Christian terms, a Hindu Reformation, complete with an assembly hall where priests did not perform rituals, only gave sermons. Hindu goal-based 'missions' came into being, as did Hindu 'fundamentalists' determined to organize, standardize and sanitize customs and beliefs. This was when increasingly the idea of dharma started being equated with rules, ethics and morality, the Ramayan and the Mahabharat were rewritten as Greek tragedies, and everything had a nationalistic fervour.

Salvation for Indian thought came when Gandhi used non-violence and moral uprightness to challenge Western might. The non-violent doctrine of Jainism, the pacifism of Buddhism and the intellectual fervour of the Bhagavad Gita inspired him. That being said, Gandhi's writings, and his quest for the truth, do show a leaning towards the objective rather than the subjective. Gandhi's satyagraha was about compelling (agraha) on moral and ethical grounds; it called for submitting to what he was convinced was the truth (satya). This may have had something to do with the fact that he trained as a lawyer in London, and learnt of Buddha and the Gita through the English translations of Orientalists such as Edwin Arnold and Charles Wilkins.