Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management (4 page)

Read Business Sutra: A Very Indian Approach to Management Online

Authors: Devdutt Pattanaik

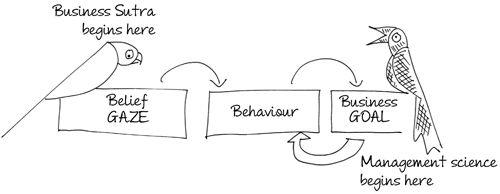

The idea I came up with finally, which I later called Business Sutra, was unique in the value it paid to belief, imagination and subjectivity.

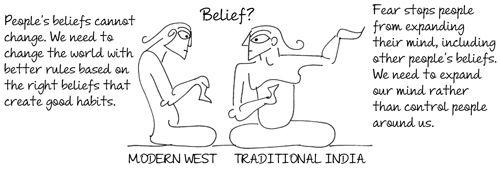

Mythologies of Indian origin value the nirguna (intangible and immeasurable) over the saguna (tangible and measurable), in other words the subjective over the objective. Subjectivity tends to be more appreciative of the irrational. Subjectivity draws attention to other subjects and their subjectivity. Respect for other people’s worldviews allows diversity.

What emerged was a management model that valued gaze over goal, accommodation over alignment. This is what, I believe, the global village needs. Its absence is why there is so much strife and conflict.

My initial observations were met with wry amusement. Modern society had bought into the ‘myth of mythlessness’ created by the scientific discourse that locates humans outside subjectivity. Most people seem to be convinced myth and mythology belonged ‘then and there’ and not ‘here and now’. No one wanted to believe that businesses were anything but rational and scientific. Moreover, for most people, mythology is religion and religion is a ‘bad’ word, hence mythology is a bad word. To be secular is to dismiss both religion and mythology, and treat those who speak of it as heretics, which did not bode well for me.

Susheel Umesh of Sanofi Aventis was the first to value my ideas on management principles derived from Indian mythology; the illustration of the yagna I drew for him several years ago still hangs in his office. I got an opportunity to present my views through

Corporate Dossier

, the weekly management supplement of the

Economic Times,

thanks to the encouragement of Vinod Mahanta, Dibyendu Ganguly and Vikram Doctor. This was a personal enterprise; professionally, no one took notice. The column, however, was widely appreciated, perhaps because of cultural chauvinism, some may argue. But gradually it caught the eye of business leaders, academicians and practitioners. They felt it articulated what many had intuitively sensed.

Santosh Desai, author of

Mother Pious Lady,

who came from the world of advertising and branding, reaffirmed my understanding of humans as mythmakers and meaning-seekers, constantly giving and receiving codes through the most innocuous of cultural practices. Rama Bijapurkar, author of

We Are Like That Only,

who came from the world of market research and consumer insights, encouraged me to find original ideas in Indian mythology that had escaped academicians and scholars who were entrenched in Western thought.

Becoming Chief Belief Officer

The tipping point came when Kishore Biyani asked me to join the Future Group. He had set up the unique retail chain, Big Bazaar, based on Indian beliefs, and had long recognized the role that culture and storytelling play in business. He was looking for someone to articulate these thoughts to his investors, to the world at large, and also to the many sceptics within his team, who were all hitherto spellbound by Western discourse. My initial conversations with him, his daughter, Ashni, as well as Damodar Mall and Tejaswini Adhikari of Future Ideas on the possibilities of mythology changed the course of my life forever.

Within the group, tea started being served in the peculiar ‘cutting chai’ glass that is found in railway stations across India to symbolically communicate the group’s determination to be grounded in simplicity and community reality. The karta ritual was initiated wherein the store manager is blindfolded in the presence of his team and his family before being given keys to the store along with his target sheet by his boss; the aim was to draw attention to the eyes, symbolically provoke a mind-shift along with the job-shift, encourage a wider, longer, deeper and more mature line-of-sight to accompany the increase in responsibilities. An abbreviated version of the gaze-based leadership model was displayed visually, using symbols, and used in leadership workshops and appraisals for senior team members so that all aspects were approached simultaneously rather than sequentially. Suddenly, the corporation seemed more rooted in culture, and not burdened by an alien imposition.

Outside the group, the designation did the trick. It opened many doors and led to many fine conversations with senior leaders and consultants of the industry that helped flesh out my idea into a full-blown theory. My interactions revealed how divorced modern business practices are from all things cultural. Very few managers saw culture as a lever; most seemed to be embarrassed by all things traditionally Indian, except Bollywood and cricket. It explained why industry is increasingly at odds with society. It became clear that professionalism and processes are aimed at domesticating people, and so could never inspire entrepreneurship, ethics, inclusiveness or social responsibility. I also realized how ideas that I found in Indian mythology helped many to join the dots in businesses very differently.

The most difficult thing about this designation has been to see how people receive new ideas. After over a century of gazing upon Indian ideas through orientalist, colonial, socialist and capitalist lenses, we are today far removed from most Indian ideas presented in this book. While many are thrilled by the rediscovery, many are eager to dismiss it: we may not be happy with what we already know, but we are terrified of exploring anything new.

The success of my

TED India

talk in Mysore 2009 and the

Business Sutra

series on CNBC in 2010 with Menaka Doshi and the viral spread of these videos through social networking sites allayed my self-doubt. The

Shastraarth

series on CNBC-Awaaz with Sanjay Pugalia in Hindi highlighted the gap between Indian beliefs and beliefs embedded in management science. It convinced me to write this book.

Design of the Book

The word ‘sutra’ in the title of the book has two very particular meanings.

- A sutra is a string meant to join dots that create a pattern. The book strings together myriad ideas from Jain, Hindu and Buddhist traditions to create a synthesized whole, for the sake of understanding the India way. Likewise, it strings Greek and biblical ideas separately to understand the Western way and Confucian and Taoist ideas to understand the Chinese way. Each of these garlands is man-made and reveals my truth, not the Truth.

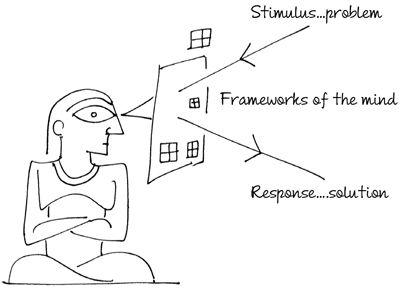

- Sutra also means an aphorism, a terse statement. The book is full of these. They are like seeds which, when planted in the mind, germinate into a plant. The nature of the plant depends on the quality of the mind. Indian sages avoided the written word as they realized that ideas were never definitive; they transformed depending on the intellectual and emotional abilities of the giver as well as the receiver. Thus, an idea is organic. Many sages chose symbols rather than sutras to communicate the idea. What appears like a naked man to one person, will reveal the nature of the mind to another. Both are right from the point of view of each individual. There is no standard answer. There is no correct answer. The point is to keep expanding the mind to accommodate more views and string them into a single whole. This approach can be disconcerting to the modern mind seeking the truth.

I call this book a very Indian approach to business for a very specific reason.

- An Indian approach traces Western ideas to Indian vocabulary. Here, dharma becomes ethics and yajaman becomes the leader. It assumes the existence of an objective truth in human affairs.

- A

very

Indian approach to business reveals the gap in the fundamental assumptions that defines management science taught in B-schools today. It celebrates my truth and your truth, and the human capability to expand the mind, thanks to imagination.

Not all will agree with the decoding of some of the popular mythological characters in this book. It may even be contrary to religious and scholarly views. This is not simply because of differences in perspective; it is also because of differences in methodology. More often than not each character in mythology is seen in isolation. But a mythologist has to look at each one relative to the rest, which helps us create the entire mythic ecosystem, where every element is unique and there are few overlaps, just like a jigsaw puzzle. The point is not so much to explain mythology as it is to derive frameworks from it.

Business is ultimately about decisions. When we take decisions, we use frameworks, either consciously or unconsciously. This book is full of frameworks, woven into each other. While frameworks of management science seek to be objective, the frameworks of Business Sutra are primarily subjective.

The book does not seek to sell these frameworks, or justify them as the truth. They are meant to be reflective, not prescriptive. They are not substitutes; they are supplements, ghee to help digest a savoury meal. The aim is to expose the reader to more frameworks to facilitate better decision-making. Apply it only if it makes sense to your logic, not because someone else ‘won’ when he applied it.

You will find no references, no testimonies or evidence, not even a bibliography. Even the ‘case studies’ are imagined tales. The aim is not to derive knowledge from the past, or to seek the consensus of other thinkers, but discover invisible levers that play a key role in business success or failure.

The number of non-English words may be mind-boggling but English words are insufficient to convey all Indian ideas. New ideas need new vehicles, hence new words. There are layers of meanings in each word, crisscrossing between sections and chapters.

A book by its very nature creates the delusion of linearity, but the subject being presented is itself not linear. Think of Business Sutra as a rangoli or kolam, patterns created by joining a grid of dots, drawn for centuries every morning by Hindu women using rice flour outside the threshold of their house. The practice is now more prevalent in the south than the north of the country. Every idea in this book is a dot that the reader can join to create a pattern. Every pattern is beautiful so long as it includes all the dots. And no pattern is perfect. Every pattern is usually an incomplete section of a larger pattern known to someone else. No pattern, no framework, no dot has an independent existence outside you. Unless you internalize them, they will not work. Currently, they are shaped by my prejudices and limited by my experiences; to work they have to become yours, shaped by your prejudices, limited by your experiences. So chew on them as a cow chews cud; eventually milk will flow.