Catastrophe 1914: Europe Goes to War (39 page)

Read Catastrophe 1914: Europe Goes to War Online

Authors: Max Hastings

Tags: #Ebook Club, #Chart, #Special

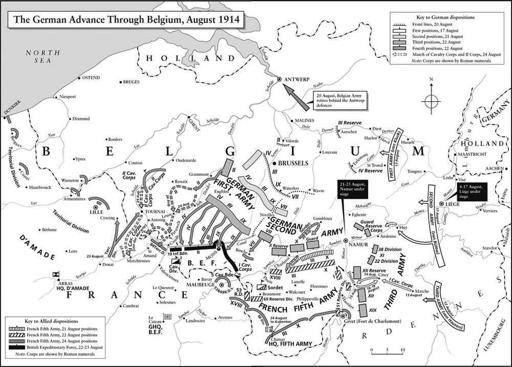

The commander-in-chief did not at first press his subordinate to attack. Thus Fifth Army was largely supine until, on 21 August, Karl von Bülow’s formations fell upon it near Charleroi. This heavily-built-up industrial region was poor country in which to fight a defensive battle, because it was difficult for artillery or infantry to gain a clear sight of the foe. That day, the Germans seized bridges across the Sambre, and held them against repeated counter-attacks. Next morning, France’s bloodsoaked 22nd, Bülow and his staff motored to a vantage point on high ground from which they could view operations. Lanrezac gave his two local corps commanders on the opposite side of the valley no orders, and thus on their own initiative they did what was expected of every French general in August. They attacked, committing their men to a succession of massed charges to recapture the river bridges. These were repulsed with 6,000 casualties.

The destruction of two colonial infantry regiments, 1st Tirailleurs and 2nd Zouaves, passed into the bloody legend of the time. There was otherworldly close-quarter strife around the Tirailleurs’ colours, which changed hands repeatedly. The regiment’s report later noted, ungrammatically but vividly: ‘the colour-bearer was killed five times’. Lt. Edward Louis Spears, British liaison officer with Lanrezac, wrote of the regiment that attacked: ‘As if at manoeuvres, in dense formation, bugles blowing, drums beating and flags flying, it had dashed to the assault with the utmost gallantry. These brave men, in the face of machine-guns and artillery whose gunners can never have dreamed of such targets … were driven back in some confusion.’ Most of Fifth Army, we should remember, was new to the ghastly experiences that French forces further south had been enduring for a fortnight. Spears met some of Lanrezac’s men preparing to renew their assaults: ‘they were like eager children, as gay as if this were the dawn of a holiday and they were presently going to march down the road to make a day of it at the local fair’. Within a few hours, their radiant spirits were extinguished in a storm of machine-gun fire and high explosives.

Lt. Spears – in those days he spelled his name ‘Spiers’ – became one of the most remarkable participants in the drama of 1914. He was twenty-eight, and an upbringing in France had conferred on him a talent rare among contemporary British soldiers – he spoke accentless French. Despite his youth and junior rank, from the first days of the campaign he made himself indispensable to the senior officers of the two allies, whose eminence intimidated him not at all. Four years later the French ambassador in London described Spears as ‘[a] most dangerous person … a very able and intriguing Jew who insinuates himself everywhere’. Many of Spears’s compatriots shared such disdainful sentiments. Later in the war Winston Churchill befriended him, and sceptical comrades sneered at the two as fellow mountebanks. But the British liaison officer became an eyewitness to crucial inter-allied exchanges, and later published a narrative of his experiences,

Liaison 1914

, which is a masterpiece.

On Fifth Army’s front on 22 August, having crushed French attacks, the Germans launched their own advance. By late afternoon Lanrezac’s centre was collapsing, and his army had fallen back in disorder some six miles. Just three German divisions had inflicted a major defeat on nine French formations. The general was at first minded to counter-attack next day. However, when confronted with bad news from every sector, at 9.30 p.m. on 23 August he ordered a general retreat, hoping to turn and meet the Germans again on better terms, in new positions further south. He was not a moment too soon: though Bülow’s army had also suffered severe losses in the Sambre battles, its divisions were now deploying in strength south of the river. The French commander’s egregious error was that, having acted sensibly in defiance of orders, he left both Joffre and his nearby British allies supposing that he intended imminently to resume the offensive – which he did not.

Between 20 and 23 August, 40,000 French soldiers died. By 29 August, total French casualties since the war began reached 260,000, including 75,000 dead. The Third and Fourth Armies in the Ardennes had suffered worst – of the Third’s 80,000 infantrymen, 13,000 had fallen. By the evening of 23 August, the ‘Battles of the Frontiers’ were over. They would remain the entire war’s bloodiest daily clashes of arms. And even as Lanrezac’s men were falling back, a few miles westwards the British Expeditionary Force met the Germans for the first time, at the dreary little Belgian industrial town of Mons.

On 3 August

The Times

’s military correspondent, that intelligent cad Col. Charles à Court Repington, declared that the Franco-German frontier would become the focus of the war’s first big military operations. He added fiercely: ‘If our troops fail at the rendezvous, history will assign our cowardice as the cause’ – meaning the sluggishness of Asquith’s government in agreeing to deploy British troops on the continent. On the 10th, Repington warned: ‘We must be prepared for a desperate enterprise on the part of the entire German navy, and for the attempted cooperation of the German army in an attack on us.’ Two days later he wrote sombrely: ‘We should not be under any illusion that the approaching

Massenschlacht

will be anything less than the most frightfully destructive collision of modern history,’ adding on 15 August: ‘It is at least possible that the war may last a long time.’

That day the British Expeditionary Force’s commander-in-chief, Sir John French, arrived at Paris’s Gare du Nord, to be greeted by a large crowd undeterred by drizzling rain. Following the field-marshal’s subsequent meeting with France’s leaders at the Elysée Palace, Sir Francis Bertie described René Viviani as ‘harassed, nervous and anxious’. Meanwhile ‘the minister for war was more anxious to display his knowledge of English than to impart valuable information’. Amid huge uncertainties and apprehensions, it is scarcely surprising that the nerves of the principal players, none of them young men, were stretched to the limit. Bertie was probably unaware that Joffre was telling his government – never mind the people of France – almost nothing about events on the battlefield.

It is an enduring British conceit that the First World War began in earnest only on 23 August, when the ‘Old Contemptibles’ of the BEF

drubbed the Kaiser’s hosts at Mons, thus saving England by their exertions and Europe by their example. In truth, of course, the French army had been engaged in murderous strife for almost three weeks before the first of the King-Emperor’s soldiers fired a shot in anger; Serbia, Poland and East Prussia were already steeped in blood.

In northern France during the first exchanges of the war the British contribution, though significant, was entirely subordinate to that of the vastly larger allied forces. Against 1,077 German infantry battalions, at the start of the campaign the French deployed 1,108, the Belgians 120 and the BEF … fifty-two. It is unlikely that the Kaiser ever spoke of Britain’s ‘contemptible little army’, as popular myth asserts, but its absurdly inadequate size justified such an appellation. French’s initial force comprised sixteen regiments of cavalry, the aforesaid fifty-two battalions of infantry, sixteen brigades of field guns, five batteries of horse artillery, four heavy batteries, eight field companies of Royal Engineers, together with service corps and suchlike supporting contingents. Later in the war – from 1916, as France became increasingly exhausted – Britain assumed a major role on the Western Front. In August 1914, however, the BEF conducted only a long retirement interrupted by two holding actions. German miscalculation and bungling, together with French mass and courage, did much more than British pluck to deny the Kaiser his victory parade down the Champs-Elysées. But this does not diminish the fascination with which posterity views the BEF’s first actions.

The Anglo-Saxon allies were warmly welcomed to the continent. After a march on 13 August Lt. Guy Harcourt-Vernon wrote: ‘Last mile ½ battalion fell out to be seized by inhabitants & dosed with water and cider. Discipline appalling.’ Unit adjutants visited brigade paymasters to exchange officers’ English gold sovereigns for local francs. A café in the Place Gambetta of Amiens adopted a custom which had spread through all Europe’s warring camps: at 9 p.m., closing time, uniformed and civilian patrons alike rose and stood at attention while the band played in succession each allied national anthem. But the old women who supervised the local public baths treated their foreign visitors – by no means mistakenly – as lambs destined for slaughter. They mopped their eyes as they distributed free tea, saying, ‘

Pauvres petits anglais, ils vont bientôt être tués

.’

The right wing of Moltke’s armies had farthest to march to do its part in the vast envelopment of Joffre’s forces. After smashing a path through Liège, two corps were detached to pursue the Belgian army, retiring north-westwards towards the fortress of Antwerp in hopes of eventual French

succour; to occupy Brussels; and to secure lines of communication. These diversions significantly weakened the main ‘Schlieffen’ thrust south. Belgian forces were incapable of major offensive action, and could most sensibly have been masked until the French were beaten, then mopped up at leisure.

The third week of August found the adjoining armies of Alexander von Kluck and Karl von Bülow, more than half a million men, plodding doggedly southwards through Belgium towards the French frontier. Some eyewitnesses who watched their progress were stricken with awe at what seemed an irresistible phenomenon. Richard Harding Davis, an American novelist and journalist, described their triumphal entry into Brussels at 3.20 p.m. on 20 August: ‘No longer was it regiments of men marching, but something uncanny, inhuman, a force of nature like a landslide, a tidal wave or lava sweeping down a mountain. It was not of this earth, but mysterious, ghostlike.’ Harding Davis marvelled at the sense of power projected by thousands of men singing ‘Fatherland, my Fatherland’ ‘like blows from a giant piledriver’.

As for their commanders, Kluck was sixty-eight years old, of non-noble background, a tough, leathery professional who had risen on merit. Bülow was also sixty-eight, a Prussian aristocrat to whom Kluck was subordinate, though in the field the latter not infrequently ignored the fact. Moltke considered Bülow the ablest of his generals, and had thus entrusted him with the most critical responsibilities, but both he and Kluck were old men, well past fitness to assume leading roles in the greatest military operations in history, as would soon become apparent. Within Bülow’s two armies both men and beasts were already feeling their feet. In just one German cavalry division, seventy horses died of exhaustion in the first fortnight of the campaign, and most of the others could scarcely raise a trot. No system was adopted for regularly resting marching men, the better to husband their strength and minister to blistered feet.

Towards them tramped the columns of the British Expeditionary Force, advancing through gently undulating countryside, basking in welcomes as warm as those its soldiers had everywhere met since disembarking at the Channel ports. ‘These French people are certainly enthusiastic beyond British comprehension,’ wrote Lord Bernard Gordon-Lennox of the Grenadiers, ‘and it would do old England a world of good to see the unbounded patriotism and

bon camaraderie

displayed on all sides.’ Some men remarked on the profusion of mistletoe in the branches of roadside trees, though relatively few would live to kiss any woman beneath

Christmas boughs. Recalled reservists made up at least half of the strength of every BEF unit: fresh from soft civilian life and wearing unbroken boots, they struggled to keep up.

Guy Harcourt-Vernon scribbled on the 22nd: ‘All day men have been gorging themselves on pears & apples. Farmer says better us than Prussians. Hear, hear!’ The BEF’s C-in-C had agreed to halt his force at the Mons–Condé canal just inside Belgium, where it could protect Lanrezac’s left, while French cavalry filled the intervening gap. But then Fifth Army received a bloody nose at Charleroi, and yielded ground. The British and French thus became perilously misaligned, with the BEF still advancing blithely, even as Lanrezac’s men were falling back.

When the khaki columns reached Mons, some thirty-five miles south of Brussels, soldiers whose faces were already reddened by the summer sun stripped off their tunics and began to dig in, to no great effect, amid the clutter of a suburban and industrial region. Buildings limited fields of fire. Towards nightfall insects began to swarm out of the waterways, causing thousands of men to curse freely as they slapped bites. In the distance to the south-east, some heard the crump of guns on Fifth Army’s front. Sir John French learned of the repulses that had been inflicted on his allies, but did not comprehend their scale – the facts that the French army had lost a quarter of its mobilised strength, while Lanrezac’s left was nine miles behind the British.

The little field-marshal remained buoyant about allied prospects. He knew there were Germans in the offing, but displayed a bizarre insouciance about placing his troops in their path. The BEF’s highly competent chief of intelligence, Col. George MacDonogh, gave warnings based on air reconnaissance and messages from Lanrezac’s staff, that three German corps were bearing down upon him. Sir John dismissed this threat, proposing to continue an advance towards Soignies. When he personally interviewed an RFC pilot who had gazed down on Kluck’s masses, the C-in-C revealed obvious disbelief, and changed the subject to quiz the troubled young man paternalistically about his aeroplane.