Catastrophe 1914: Europe Goes to War (84 page)

Read Catastrophe 1914: Europe Goes to War Online

Authors: Max Hastings

Tags: #Ebook Club, #Chart, #Special

The men of 7th Division had to learn their business under a storm of incoming bullets and shells. Some officers confused idiocy with courage: Lt. Col. Walter Loring of 2nd Warwicks rode up the Menin road at the head of his battalion on an enormous white horse. He cursed when a bullet struck his heel, and after having the wound dressed insisted on remounting. The horse was soon killed, and Loring took another, which also fell. The colonel was eventually killed on the 24th, hobbling among his men, urging them on with one foot in a carpet slipper. He was the first of three brothers to die in the opening year of the conflict.

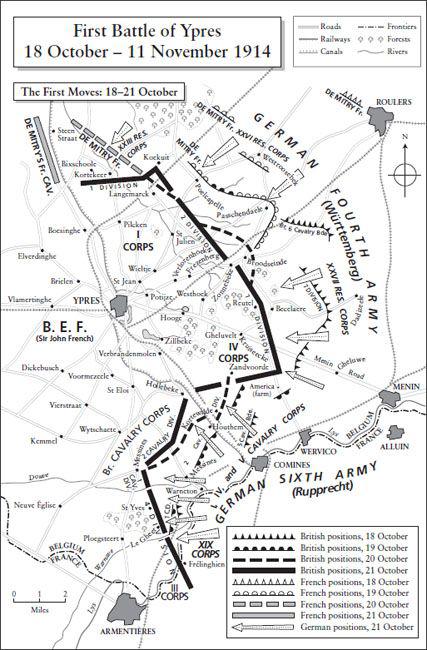

The village of Passchendaele was lost, and remained in enemy hands for three years. Orders reached the forward positions to dig in. Men asked: with what? Many had lost or rashly discarded their entrenching tools, and none had heavy spades. They scraped as best they could, some with bare hands. The 21st proved another day of savage action and losses. The first troops arriving from the Aisne began to move into the line, one unit after another arriving just in time to meet new waves of Germans, who were soon attacking by night as well as by day, on an ever broader front. But the Kaiser’s soldiers lost heavily on both the 20th and the 21st, and felt anything but invincible. Marwitz, commanding the cavalry, wrote on the 22nd, after studying the British positions: ‘The entire countryside here is one mass of small enclosed fields and hedges reinforced with wire. How are we meant to attack through that? The enemy exploits its potential skilfully, firing from inside houses and trenches which they have dug extremely rapidly.’

A German corporal who took part in the initial assault on Langemarck, north of Ypres, wrote wearily afterwards: ‘Who that day or during the days that followed had any idea about what was happening or what either we or the enemy intended? … Quite suddenly bursts of shrapnel spread death and destruction on our positions. What I saw and experienced … was amongst the sort of images that the wildest imagination can dream up. What was left of our division? … In every piece of meadow, behind every hedge, were bands of men, some large, some small, but what were they doing? What could they do?’ Early that afternoon of the 21st, one battered German regiment broke and ran after all its officers had become casualties. By nightfall every house in the village of Poelkapelle was crowded with wounded brought back from the shambles at Langemarck. When the attack was renewed next day, the outcome was identical.

For decades afterwards, German nationalists sought to evoke a supposed ‘Spirit of Langemarck’, signifying exemplary courage in the face of adversity. This was a myth, which masked the fact that the German attacks of 21–23 October were exercises in futility, matching anything the French had done in the Battles of the Frontiers. ‘A bloody day indeed,’ Bavarian Capt. Ottmar Rutz wrote ruefully of the 21st, listing his close friends among officers killed leading attacks down the road to Ypres. British firing continued into the night: ‘It seemed as though nobody was meant to quit this place alive.’ Next morning, with great difficulty food was brought forward to give the Germans who had been detailed to renew the assault their first hot meal for two days – and the last many ever ate. Falkenhayn’s Fourth Army complained that positions won at heavy cost by day were lost again during the night.

Though Ypres and Sir Douglas Haig’s I Corps became the principal focus of German assaults, French and British troops further south in front of Armentières and behind La Bassée fought their own bitter battles throughout the last fortnight of October. GHQ was slow to comprehend the scale of the German effort, and still dispatched battalions into the line with orders to assume that they themselves would shortly be doing the attacking. They learned differently. ‘Everywhere we advance we find Germans in front of us,’ wrote Grenadier George Jeffreys. Wilfrid Abel-Smith fulminated on 22 October: ‘It is all rot saying we have nothing in front of us. There are heaps of Germans, and, as an army, they are very good, and their gunners are perfect … No doubt we will kill heaps of Germans but there are always heaps more …’

Many British soldiers’ clothing was in tatters after their travails since August. Some wore civilian trousers; veteran Welch Fusilier Frank Richards affected a knotted handkerchief in place of his long-lost service cap. He did not care: ‘we looked a ragtime lot, but in good spirits and ready for anything that turned up’. Just east of Fromelles, his unit unbuckled its entrenching tools: ‘Little did we think … that we were digging our future homes,’ Richards wrote. Two Indian divisions joined the right of the BEF’s line on 22 October. The reinforcement was desperately needed, and the first Indian soldier to win a VC was a Baluchi, Sepoy Khudadad Khan, who gained his medal manning a machine-gun in Hollebeke.

It was widely suggested, however, that the Indian corps was ill-suited to continental campaigning. Frank Richards, who had served for years in the subcontinent, wrote later with a ranker’s contempt: ‘native infantry were

no good in France. Some writers in the papers wrote at the time that they couldn’t stand the cold weather; but the truth was that they suffered from cold feet, and a few enemy shells exploding around their trenches were enough to demoralize the majority.’ Indian cavalry corps commander Lt. Gen. Mike Rimington declared scornfully that his men were ‘only fit to feed pigs’. This was grossly unjust: Indian troops taught the rest of the BEF the art of patrolling. But there was a core of truth in the view that it was brutal, even in the British Empire’s hour of need, to expose mercenaries from the far side of the world to the appalling cultural shock of the struggle in Flanders.

The Germans attacked by night as well as by day, and many actions were fought out by the light of blazing buildings. One group approached the Grenadiers in darkness on 21 October, crying out almost believably, ‘We are the Coldstream!’ But the Grenadiers glimpsed spiked helmets silhouetted against the skyline, and shot them down mercilessly. An officer wrote: ‘it is too much like shooting a flock of sheep, poor things. They have discipline, and do what they are told, but their attacks at night in this wood developed into the poor devils wandering rather aimlessly about under our terrific rifle fire.’ Livestock roamed untended, and some men milked cows between bombardments. In one attack, the Germans drove cattle ahead of their troops: beasts and men were slaughtered together.

The war diary of 2nd Oxf & Bucks recorded on 22 October: ‘they came on in thick lines, and our firing was steady and the light sufficiently good to enable a fair aim to be taken’; the foremost Germans fell within twenty-five yards of the battalion’s positions. Though British shrapnel inflicted some damage, artillery ammunition was short on both sides: rifles and machine-guns were responsible for most of the killing. In one notorious assault at Langemarck, fifteen hundred young Germans were killed and six hundred prisoners taken. Human fortitude was tested to the limit by the tumult of Ypres. Extreme penalties, or at least the threat of them, were periodically invoked to hold men to their duty. Pte. Edward Tanner of the Wiltshires was shot by a firing squad on 29 October, having been apprehended behind the lines in civilian clothes. L/Sgt. William Walton deserted from the King’s Royal Rifle Corps near Ypres, and was duly executed on his recapture, after remaining on the run for several months. Lionel Tennyson threatened to shoot the next man of his who returned prematurely from a listening patrol in no man’s land. It was now that this last phrase – used in medieval times to describe a patch of unowned ground north of London’s city walls where executions were carried out – first

entered soldiers’ vernacular, denoting the space between rival trenches, which might vary from fifty yards to two hundred according to the vagaries of the terrain.

Each side’s accounts of hardship, misery, terror, despair and sacrifice marched in step during the successive clashes at Ypres. It was a delusion shared by almost every man that the BEF alone confronted the enemy’s might. Something of the same feeling reached back to Britain. Churchill wrote of his own deep gloom in those weeks: ‘the sense of grappling with and being overpowered by a monster of appalling and apparently inexhaustible strength on land … oppressed my mind’. In November there was a new invasion scare at home, which briefly infected Kitchener and Churchill, and reinforced their illusions about the limitless resources at the Kaiser’s disposal.

It was true that the British sector in Flanders was the focus of a huge effort by Falkenhayn, but the French suffered plentiful tribulations of their own, and made a critical contribution to holding the line. German interrogators reported French prisoners complaining about the allegedly poor showing of their British neighbours, in a fashion that mirrored their allies’ ruderies about themselves. South of the BEF’s frontage, Foch’s men counter-attacked again and again, maintaining pressure on the enemy. Sgt. Paul Cocho, thirty-five-year-old owner of a Breton grocery shop and the father of four young children, went into action for the first time in Flanders, and was stunned by the experience: ‘I did not imagine that war would be like this … I have seen in our regiment so much chaos and so little proper leadership; I have seen wounded poorly cared for … For the first two days we had to make do with small pieces of dried bread as food, though we were hardly hungry amid so much profoundly emotional experience. We had wine to drink at first because some resourceful chaps went and pillaged the cellars of wrecked houses, then later we had only cold coffee.’ Cocho described his experiences as a prolonged nightmare, from which he was awakened only by being evacuated sick at the end of November.

On 23 October French infantry launched a desperate attempt to retake Passchendaele. Among the foremost of the attackers was their commander, Gen. Moussy, who urged them on, saying, ‘

Allons, allons, mes enfants. En avant! En avant!

’ His men replied, ‘

Bien, mon général!

’ But ever more often in the face of the enemy’s fire they dropped back to seek cover, and the advance lost momentum. Moussy tried a joke: ‘

Il faut absolument arriver a Passchendaele ce soir, ou pas de souper, pas de souper!

’ Whether or not the survivors got supper, the French failed to get Passchendaele. The British

felt that Moussy himself behaved more like a company commander than a general, but more than a few of their own leaders emulated him. Whatever claims were made about ‘château generalship’ later in the war, at First Ypres senior officers on both sides exposed themselves freely, and perished in proportion.

A contest in pain and sacrifice was unfolding. German soldier Paul Hub wrote home on 23 October: ‘Maria, this sort of war is so unspeakably miserable. If only you saw a line of stretcher-bearers with their burdens, you’d know what I mean. I haven’t had a chance to shoot at all yet. We have to deal with an unseen enemy.’ Blast cost Hub the permanent loss of his hearing, and many of his comrades suffered worse fates. After being badly shot in the chest north of Ypres, a German NCO named Knauth wrote later that he was surprised to find himself thinking with relief, ‘Well, you will be spending Christmas at home.’ And still Falkenhayn’s offensive, and his men’s sufferings, continued. Sgt. Gustav Sack described his unit’s meagre rations in a letter to his wife Paula, written near Péronne on 26 October. At 7 a.m. they drank coffee or tea, indistinguishable from each other in texture. Late at night they received field-kitchen soup and ration bread. Instead of a continuous trench, men occupied foxholes in which they slept on straw. As for the war, ‘everything is quite, quite different and more insane than you could suppose possible … You don’t see anything, although the wicked enemy’ – this was his heavy humour – ‘is only 3–400m away, but you hear plenty.’ He added in another letter: ‘I am freezing! Tonight I am on outpost duty from seven to seven – the moon high, cotton-wool clouds, nice sunrise, partridges everywhere, everything very picturesque – but cold, cold, cold and hungry!’

Every British soldier now knew that the cessation of an enemy artillery bombardment signalled the onset of an infantry assault. Capt. Henry Dillon wrote to his parents of meeting a night attack on 24 October: ‘A great grey mass of humanity was charging, running for all God would let them straight on to us not 50 yards off – about as far as the summer-house to the coach-house … As I fired my rifle the rest all went off almost simultaneously. One saw the great mass of Germans quiver. In reality some fell, some fell over them, and others came on. I have never shot so much in such a short time … My right hand is one huge bruise from banging the bolt up and down … The firing died down and out of the darkness a great moan came. People with their arms and legs off trying to crawl away; others who could not move gasping out their last moments with the cold night wind biting into their broken bodies and the lurid red glare of a

farmhouse showing up clumps of grey devils killed by the men on my left further down. A weird, awful scene; some of them would raise themselves on one arm or crawl a little distance.’

Dillon was one of few men on either side who had sufficient emotion to spare to give a thought to those remote masters of mankind who had unleashed the slaughter: ‘Well, I suppose if there is a God, Emperor Bill will have to come to book some day. When one thinks of the misery of those wounded and later on wives, mothers and friends, and to think that this great battle where there may have been half a million on either side is only on a front of about 25 miles, and that this sort of thing is now going on on a front of nearly 400. To think that this man could have saved it all!’