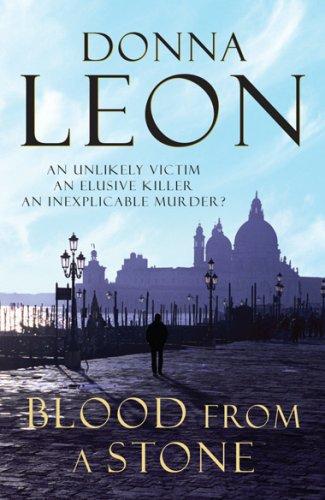

CB14 Blood From A Stone (2005)

DONNA

LEON

FROM

A

STONE

a r r o w b o o k s

a r r o w b o o k s

This eBook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorised distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the author’s and publisher’s rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

Version 1.0

Epub ISBN 9781407070445

Reissued by Arrow Books 2009

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

Copyright © Donna Leon and Diogenes Verlag AG Zurich, 2005

Donna Leon has asserted her right under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988, to be identified as the author of this work.

This book is a work of fiction. Names and characters are the product of the author’s imagination and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

This book is sold subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, resold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher’s prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

First published in Great Britain in 2005 by William Heinemann First published in paperback in 2006 by Arrow Books

This edition published in 2009 by Arrow Books The Random House Group Limited 20 Vauxhall Bridge Road, London, SW1V 2SA

Addresses for companies within The Random House Group Limited can be found at:

www.randomhouse.co.uk/offices.htm

The Random House Group Limited Reg. No. 954009

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

ISBN 9780099536543

The Random House Group Limited supports The Forest Stewardship Council (FSC), the leading international forest certification organisation. All our titles that are printed on Greenpeace approved FSC certified paper carry the FSC logo. Our paper procurement policy can be found at:

www.rbooks.co.uk/environment

Typeset by SX Composing DTP, Rayleigh, Essex Printed in the UK by CPI Bookmarque, Croydon, CR0 4TD

for Gesine Lübben

BLOOD

FROM

A

STONE

Donna Leon has lived in Venice for many years and previously lived in Switzerland, Saudi Arabia, Iran and China, where she worked as a teacher. Her previous novels featuring Commissario Brunetti have all been highly acclaimed; including

Friends in High Places

, which won the CWA Macallan Silver Dagger for Fiction,

Through a Glass, Darkly, Suffer the Little Children

, and most recently,

The Girl of His Dreams

.

Praise for

Blood from a Stone

and Donna Leon

‘As usual, the real star of the book is Venice, vividly depicted in the rain, and Leon’s dissection of the intrigue and corruption in Italian politics, partly through Brunetti’s conversations with his wife, makes absorbing reading, with a typically cynical conclusion.’

Sunday Telegraph

‘It’s the ingenious way that she knits up-to-date plots with the history of the city that pleases . . . Her passion for all things Venetian – churches, palaces, statues and especially the food – comes over loud and clear whenever Brunetti steps from his apartment into the street . . . No one writes about the grey areas of life better.’

Guardian

‘It would be simply perverse not to acknowledge [Leon’s] skill . . . The reader comes to look forward to Paola’s elegant Venetian lunches as much as Brunetti does . . . The plot of

Blood from a Stone

both stands up to and complements the cast . . . Comfort reading of the highest order.’

TLS

Also by Donna Leon

Death at La Fenice

Death in a Strange Country

The Anonymous Venetian

A Venetian Reckoning

Acqua Alta

The Death of Faith

A Noble Radiance

Fatal Remedies

Friends in High Places

A Sea of Troubles

Wilful Behaviour

Uniform Justice

Doctored Evidence

Through a Glass, Darkly

Suffer the Little Children

The Girl of His Dreams

Weil ein Schwarzer hässlich ist.

Ist mir denn kein Herz gegeben?

Bin ich nicht von Fleisch und Blut?

Thus a Blackmoor is considered ugly.

Didn’t I receive a heart as well?

Aren’t I made of flesh and blood?

—Mozart,

Die Zauberflöte

Two men passed under the wooden arch that led into Campo Santo Stefano, their bodies harlequined by the coloured Christmas lights suspended above them. Brighter light splashed from the stalls of the Christmas market, where vendors and producers from different regions of Italy tempted shoppers with their local specialities: dark-skinned cheeses and packages of paper-thin bread from Sardinia, olives in varying shape and colour from the entire length of the peninsula; oil and cheese from Tuscany; salami of all lengths, compositions, and diameters from Reggio Emilia. Occasionally one of the men behind the counters shouted out a brief hymn to the quality of his wares: ‘Signori, taste this cheese and taste heaven’; ‘It’s late and

I want to go to dinner: only nine Euros a kilo until they’re gone’; ‘Taste this pecorino, signori, best in the world’.

The two men passed the stalls, deaf to the blandishments of the merchants, blind to the pyramids of salami stacked on the counters on either side. Last-minute buyers, their number reduced by the cold, requested products they all suspected could be found at better prices and of more reliable quality at their local shops. But how better to celebrate the season than by taking advantage of shops that were open even on this Sunday, and how better to assert one’s independence and character than by buying something unnecessary?

At the far end of the

campo

, beyond the last of the prefabricated wooden stalls, the men paused. The taller of them glanced at his watch, though they had both checked the time on the clock on the wall of the church. The official closing time, seven-thirty, had passed more than a quarter of an hour before, but it was unlikely that anyone would be out in this cold to check that the stalls ceased trading at the correct time. ‘

Allora?

’ the short one asked, glancing at his companion.

The taller man took off his gloves, folded them and put them in the left pocket of his overcoat, then jammed his hands into his pockets. The other did the same. Both of them wore hats, the tall one a dark grey Borsalino and the other a fur cap with ear flaps. Both had woollen scarves wrapped around their necks,

and as they stepped beyond the circle of light from the last stand, they pulled them a bit higher, up around their ears, no strange thing to do in the face of the wind that came at them from the direction of the Grand Canal, just around the corner of the church of San Vidal.

The wind forced them to lower their faces as they started forward, shoulders hunched, hands kept warm in their pockets. Twenty metres from the last stall, on either side of the way, small groups of tall black men busied themselves spreading sheets on the ground, anchoring them at each corner with a woman’s bag. As soon as the sheets were in place, they began to pull samples of various shapes and sizes from enormous sausage-shaped bags that sat on the ground all around them.

Here a Prada, there a Gucci, between them a Louis Vuitton: the bags huddled together in a promiscuity usually seen only in stores large enough to offer franchises to all of the competing designers. Quickly, with the speed that comes of long experience, the men bent or knelt to place their wares on the sheets. Some arranged them in triangles; others preferred ordered rows of neatly aligned bags. One whimsically arranged his in a circle, but when he stepped back to inspect the result and saw the way an outsized dark brown Prada shoulder bag disturbed the general symmetry, he quickly reformed them into straight lines, where the Prada could anchor their ranks from the back left corner.

Occasionally the black men spoke to one another, saying those things that men who work together say to pass the time: how one hadn’t slept well the night before, how cold it was, how another hoped his son had passed the entrance exam for the private school, how much they missed their wives. When each was satisfied with the arrangement of his bags, he rose to his feet and moved back behind his sheet, usually to one corner or the other so that he could continue to talk to the man who worked next to him. Most of them were tall, and all of them were slender. What could be seen of their skin, their faces and their hands, was the glossy black of Africans whose ancestry had not been diluted by contact with whites. Whether moving or motionless, they exuded an atmosphere not only of good health but of good spirits, as if the idea of standing around in freezing temperatures, trying to sell counterfeit bags to tourists, was the greatest fun they could think of to have that evening.

Opposite them a small group was gathered around three buskers, two violinists and a cellist, who were playing a piece that sounded both baroque and out of tune. Because the musicians played with enthusiasm and were young, the small crowd that had gathered was pleased with them, and not a few of them stepped forward to drop coins into the violin case that lay open in front of the trio.

It was still early, probably too early for there to be much business, but the street vendors were

always punctual and started work as soon as the shops closed. By ten minutes to eight, therefore, just as the two men approached, all of the Africans were standing behind their sheets, prepared for their first customers. They shifted from foot to foot, occasionally breathing on to their clasped hands in a futile attempt to warm them.

The two white men paused just at the end of the row of sheets, appearing to talk to one another, though neither spoke. They kept their heads lowered and their faces out of the wind, but now and then one of them raised his eyes to study the line of black men. The tall man placed his hand on the other’s arm, pointed with his chin towards one of the Africans, and said something. As he spoke, a large group of elderly people wearing gym shoes and thick down parkas, a combination that made them look like wrinkled toddlers, flowed around the corner of the church and into the funnel created by the buskers on one side, the Africans on the other. The first few stopped, waiting for those behind to catch up, and when the group was again a unit, they started forward, laughing and talking, calling to one another to come and look at the bags. Without pushing or jostling, they assembled themselves three-deep in front of the line of Black men and their exposed wares.