Challenging Depression & Despair: A Medication-Free, Self-Help Programme That Will Change Your Life (8 page)

Authors: Angela Patmore

Tags: #Self-Help, #General

Eminent critics like Jeffrey Masson

4

and Peter Breggin

5

say mental illness labels need to be viewed with extreme caution, and Masson, himself a former psychoanalyst and custodian of Freud’s papers, says they are more akin to intellectual flag-waving than useful tools in diagnosis.

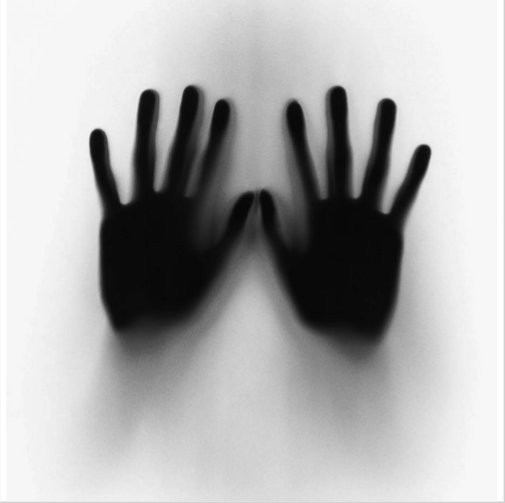

WOUNDING THE MIND

Another term commonly applied to depressed people is that they were

traumatised

by some terrible experience at some time in their lives, and this is why they are now ‘clinically depressed’. Having been ‘traumatised’, of course, there is little hope for them.

•

They will have to be wrapped in cotton wool from now on.

•

Their minds are like mangled cars about to be towed away to the breakers after a smash.

•

Only years of expensive counselling or psychotherapy can possibly restore their mutilated psyches.

•

They will need all the drugs they can get.

•

They needn’t think of going back to work, even supposing they were thinking of it.

•

They should avoid any excitement. They could be kicked to death by butterflies, so fragile is their sanity now.

And so on – you get my drift.

Traumatised

. We hear it all the time – schoolchildren have seen an accident in the playground and are therefore ‘traumatised’. A woman has been attacked in the street and is ‘traumatised’. Bank staff who were on duty during a raid have all been ‘traumatised’. Viewers can apparently even be ‘traumatised’ by watching a particularly challenging episode of

EastEnders

.

People in Haiti must surely have been ‘traumatised’ by the devastating earthquake that struck their poverty-stricken state at the beginning of 2010. Yet some of those pulled out of the rubble in Port-au-Prince after days without food or water were actually smiling and talking normally. Incredibly, one woman was cheerfully

singing

. News cameras filmed her being driven away in the front passenger seat of a four-by-four, her features as casual and composed as someone being picked up after work. How could this be? Surely she should be

devastated

(another very popular media disaster word). She must be

pretending

to be OK. She will surely

break down later.

PROBLEMS WITH ‘PTSD’

In the West, the diagnosis of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, or PTSD, has come under attack from a variety of mental health experts on the grounds that it may be misleading, unscientific and potentially disabling to the victim.

6

The diagnosis has arisen because of an influential theory – that the

mind can be wounded

. This theory may in fact be wrong.

The word ‘trauma’, which has slipped into the vernacular during any discussion on disaster victims, is Greek for ‘injury’. Saying that the

psyche

(more Greek) has been injured when it has no corporeal form is a poetic and powerful metaphor. It helps others who have not shared a terrible experience to understand the intensity of mental suffering involved, and to treat the sufferer with compassion and respect. But whether it is literally true that the psyche can be injured is a very moot point. As I explained in the relevant analysis in my book on ‘stress’:

To describe someone as ‘traumatised’ presupposes that painful emotions and experiences are wounds or abrasions in need of medical treatment; that they are not normal to life; that human beings cannot absorb and respond to them successfully; that they cannot recover, learn and grow. Survivors who are medically labelled in this way may end up not survivors at all, but ‘victims’, thinking that they are ‘psychologically scarred’ or ‘emotionally crippled’, or that they are owed compensation, or that some

person or authority must rectify whatever misery and fear they may have felt.

7

Dr James Thompson, one of the first British psychiatrists to popularise the PTSD diagnosis in the UK, says that it has become a safety blanket that protects people from worrying questions about their competence in a crisis. He says:

Knowledge of PTSD and its symptoms is now so widespread – I blame myself … There is pressure from people who are stressed and agitated: ‘Say I am traumatized – I fit the disorder.’ The motive is clear: which description would you prefer about yourself: ‘He collapsed because of the

extreme stress

placed upon him’, or ‘He collapsed because he is a weak, fragile individual who could not cope with life’?

8

‘Suffering from PTSD’ would absolve this person from responsibility for not coping, whereas just being ‘fragile’ would not.

Post-incident debriefing can make you worse

The cluster of reactions that have come to be called ‘PTSD’ may be distressing, painful and frightening. But if they happen to be the means whereby the brain gradually comes to terms with distressing events (flashbacks, for example, may be prompts to think about a memory that is deliberately being avoided), then this process may be prolonged by ill-advised interventions like ‘post-incident debriefing’ that require the survivor to revisit his feelings again and again. Some very well conducted studies have shown that these medical interventions make the victim worse, not better.

9

Indeed, if therapy is forced on the victim in the immediate aftermath, it may have a nocebo effect. Medical intervention after a disaster may create in the mind of the survivor the idea that his or her reactions are abnormal and a sign of mental illness, and that he or she is therefore mentally ill. Such fears can predispose the sufferer to pessimism, anxiety, helplessness and disease.

So if you have been ‘diagnosed’, don’t just sit there and succumb. Your brain has literally billions of neurons, and most of them aren’t being used (most of them have

never

been used). Scientists know that the brain’s spare storage capacity is prodigious, and it has seemingly miraculous untapped powers of recovery just lying there, waiting to help you survive and grow, waiting for you to say,

Blast all this. I’m going to get better.

The ‘nocebo effect’ routed

In J. R. R. Tolkien’s

Lord of the Rings,

King Théodon sits staring and frozen to his throne, unable to get his act together for the coming war because his sinister adviser Grimer Wormtongue keeps whispering that he is weak and hopeless. When the wizard Gandalf kicks Grimer out of the palace, the King resumes his heroic power.

Just remember the lady who sang in Port-au-Prince. Her hair may have been sticking out and her face may have been covered in cement dust, but her human spirit was alive and well, thank you very much, doctor.

NOTES

1

. See, for example, Helen Pilcher, ‘The science of voodoo: when the mind attacks the body’,

New Scientist,

2708, 13 May 2009.

2

. Angela Patmore,

The Truth About Stress.

Grove Atlantic, 2006, pp. 274–5.

3

.

The Truth About Stress,

pp. 6–7.

4

. Jeffery Masson,

Against Therapy,

foreword Dorothy Rowe. Collins, 1989.

5

. Peter Breggin,

Toxic Psychiatry.

St Martin’s Press, 1991. Peter R. Breggin MD has been called ‘the conscience of psychiatry’ for his efforts to reform the mental health field. He has written a number of books on caring psychotherapeutic approaches and the escalating overuse of psychiatric medications, oppressive diagnosing and drugging of children, involuntary treatment, electroshock and lobotomy.

6

. See, for example,

The Truth About Stress,

pp. 249–75.

7

.

The Truth About Stress,

p. 259.

8

. Quoted in Kevin Toolis, ‘Shock tactics’,

Guardian Weekend,

13 November 1999.

9

. See, for example, J. Bisson, P. Jenkins

et al.,

‘Randomised controlled trial of psychological debriefing for victims of acute burn trauma’,

British Journal of Psychiatry

, 171, 1997, pp. 78–81; R. A. Mayou, A. Ehlers and M. Hobbs, ‘Psychological debriefing for road traffic accident victims: three-year followup of a randomised controlled trial’,

British Journal of Psychiatry

, 176, 2000, pp. 589–93.

That’s right – lie there in your herbal ‘de-stressing’ bath.

Have a good soak. Play with your rubber duck if you like – I’ve nothing against relaxation.

So long as you realise that, when you get out of that extremely relaxing bath, you will have exactly the same set of problems as you did when you got into it.

Just being calm doesn’t solve problems. What it

can

do is to sooth you into thinking things aren’t really that urgent or important, when in fact they may

be

that urgent and important. Self-sedation can enable people who are already prone to helplessness and problem-avoidance and who face serious challenges requiring urgent action to go bumbling on for a bit longer without doing anything to help themselves – during which time their problems may very well have ballooned out of control. No wonder they are also depressed.

Yet people

behave

like this because they have been told to avoid something called ‘stress’. The National Health Service spends millions of pounds it can ill afford on drugs intended to alleviate the said ‘stress’. We chemically cosh our children and our old folk as well as ourselves to achieve the optimum state of nation sedation. ‘Anything for a quiet life’ has become our watchword.

THE ‘STRESS’ BUSINESS

So-called ‘stress management’ experts do not like me. A lot of people who make a handsome living from ‘stress’ expertise and ‘stress’ remedies would like to see me at the bottom of a pond. This is because I have exposed the flaws in their so-called scientific evidence and questioned the efficacy and effectiveness of their techniques. My book

The Truth About Stress

offers 400 pages of evidence plus 40 pages of scientific references to show that the unregulated ‘stress’ industry – with its 15 million websites and its millions of practitioners, some of them completely unqualified and spouting pseudo-scientific rubbish – is harming people and making them depressed.

For a start the whole stress business, even on its own terms, has failed. The more the industry plies its trade and enlarges its membership base (growing at a rate of 804% in 12 years) the more the ‘stress’ statistics skyrocket. Practitioners can’t even tell us under the Trade Descriptions Act what they are managing. Plus they haven’t managed it. During the year I spent typing up my book, according to the Health and Safety Executive (HSE) yet another 245,000 people in the UK ‘became aware’ that they were suffering from ‘stress’.

What are stress sufferers suffering from?

BBC TV filmed me a while back unfurling a list of over 650 different definitions on Paddington station, with commuters coming over and adding more. Meanings come from the scientific literature, from health authorities, from stress management persons and sufferers. Many are opposites. The HSE, for instance, use the s-word to mean a type of response (a ‘natural reaction’). Yet some scientists who specialise in the field like Professor Angela Clow use it to mean a type of stimulus (she talks about ‘responses to stress’ and cortisole as ‘a biomarker of stress’). Professor Stafford Lightman, another authority, uses it to mean both. He says: ‘We’ve been involved in an intensive programme to design a pill which can counter the effects of stress. And the way to do this is to block the first chemical made by the hypothalamus in the brain which actually controls the whole of the stress response.’

1

So now we can have the same word used to mean two opposites in the same explanation from one authority. In any other field of science this would not be tolerated. Even the éminence grise of ‘stress’ expertise, Professor Cary Cooper, has said on numerous occasions that stress is when something: ‘Stress occurs when pressure exceeds your perceived ability to cope.’ But this is not a definition. The definition of ‘cat’ is not ‘when something is furry’.