Charles Dickens: A Life (42 page)

Read Charles Dickens: A Life Online

Authors: Claire Tomalin

Tags: #Biographies & Memoirs, #Arts & Literature, #Authors

Hurrying back to London for a rehearsal and a committee meeting at the Home, he heard that his father was dangerously ill and about to undergo surgery on his bladder. The Dickens parents were no longer living in Lewisham but lodging in Keppel Street, between Gower Street and Russell Square, in the house of a Dr Davey, to whom Dickens had sent his father for medical advice. The Daveys had become friends as well as landlords, and it was Davey who called the surgeon and alerted Dickens. He arrived at his father’s bedside almost as the surgery took place: ‘He bore it with astonishing fortitude, and I saw him directly afterwards – his room, a slaughter house of blood. He was wonderfully cheerful and strong-hearted.’

23

Dickens went out to collect some medicine, and then to Devonshire Terrace, where he found the children happy and played with baby Dora, and wrote reassuringly to ‘My Dearest Kate’ saying he hoped to return to Malvern the following day, which he did.

Three days later he was in London again, to more bad news of his father’s condition. He was at the bedside at eleven at night on 30 March and saw that John Dickens was unable to recognize anybody. The Daveys’ house was now crowded with members and connections of the family: Alfred, who had travelled down from his railway job in Yorkshire, Augustus, Letitia and Henry Austin with Mrs Austin senior, Fred’s Weller sisters-in-law, the widow of Dickens’s old friend Charles Smithson, and Amelia Thompson. Dickens stayed beside his father until he died at about five thirty in the morning: ‘I remained there until he died – O so quietly … I hardly know what to do,’ he told Forster.

24

But he did know exactly what to do, and as his father died he took his mother in his arms and they wept bitterly together. This was the description given by Mrs Davey, who said that he behaved throughout with great tenderness and told his mother that she could rely upon him for the future. It was necessary reassurance, since his father’s effects were valued at under £40. Dickens immediately paid whatever his father owed, and his mother stayed with Letitia while he found her a house of her own, in Ampthill Square, close to Somers Town, where they had all lived together thirty years before.

He put notices of his father’s death in the

Daily News

, the

Morning Post

and

The Times.

He was too distressed to sleep and was up for three nights, much of them spent walking the streets. On the 2nd of April, his wedding anniversary and Forster’s birthday, the two men drank Catherine’s health together, ‘with loud acclamations’ he told her.

25

The next day he wrote to Forster asking him to accompany him to Highgate Cemetery to choose the ground for his father’s grave. Forster had dashed to Bulwer’s place at Knebworth for rehearsals and returned to go with him, and on the day of the funeral the two went together again in the morning to Highgate, before both taking the train to Malvern to be with Catherine. The shuttling to and fro continued, and the rehearsals. There were a few kindly obituary notices for John Dickens in the papers. Dickens remembered to book Fort House at Broadstairs for the summer, from mid-May to the end of October.

A week later he was in London to preside at the dinner of the General Theatrical Fund, calling at Devonshire Terrace first to see the children in the care of their nurses, and playing with Dora, now nine months old. She seemed perfectly well when he left her for the dinner, but even as he was making his speech she suffered a convulsion and died quite suddenly. A messenger was sent to the dinner; Forster was called out and decided to let Dickens finish his speech before telling him what had happened. Forster then travelled to Malvern again, taking a letter from Dickens, to tell Catherine. Another Highgate funeral had to be planned and carried out, and Catherine brought to London and comforted.

Meanwhile the royal command performance of

Not So Bad as We Seem

was due on 16 May, to be given at the London home of the Duke of Devonshire, necessitating rehearsals, dinners, fitting of costumes, consideration of questions of etiquette concerning the royal party, and special white satin playbills to be made for them with gold and silver fringes. Bulwer’s estranged and angry wife threatened to turn up in the audience dressed as an orange girl in order to distribute a rude memoir of her husband, and Dickens alerted his friend Chief Inspector Field of the Metropolitan Police detectives to look out for her on the night and deal tactfully with her if necessary. All went well, and the Queen found the play ‘full of cleverness, though rather too long’ – no doubt a standard royal complaint – but she found the acting of Dickens, ‘the celebrated author’, admirable, and enjoyed the ‘

select

supper with the Duke’ afterwards.

26

Her presence did what was wanted, giving a boost to the Guild and encouraging contributions to its funds.

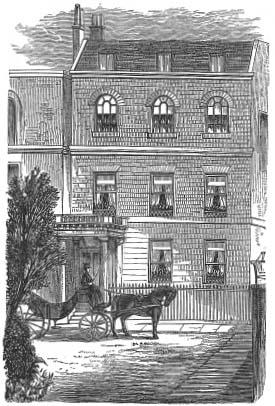

Dickens took a lease on Tavistock House in 1851, intending to keep it for life.

After this busy and distressing time the Dickens family could at last get to Broadstairs, although with many returns to London. Dickens went to the Derby with Wills, visited Charley at Eton, attended the Duke of Devonshire’s supper and ball for the cast of the play, and a banquet given by Talfourd in belated honour of

Copperfield

, to which Thackeray and Tennyson both came. There were more theatricals, with the first performance of the farce he and Mark Lemon had concocted together,

Mr Nightingale’s Diary

, which gave them both the chance to appear in many different disguises and to ad-lib to their heart’s content, Dickens wildly impersonating Mrs Gamp and Sam Weller at different moments. It was a big success with the public in London and the provincial towns to which they took it, and allowed him to prove once and for all that he could rival the man who had first inspired him, Charles Mathews, master of the monopolylogues.

In July he finally acquired another large London house with a garden, Tavistock House in Tavistock Square, for £1,500. It was in very poor condition and needed a great deal of work before the family could move in. His friend, the impoverished artist Frank Stone, had lived in it with his family, and Dickens now lent them Devonshire Terrace. He took a fifty-year lease on Tavistock House, saying he intended it to last out his life, and sent in an army of workmen.

27

Back in Broadstairs, he invited Forster for three sunny weeks in September, then in October Stone came down with Augustus Egg.

Egg had been in love with Georgina for some time and now proposed to her. He was a handsome and sweet-natured man, a good friend of Dickens and a successful painter who could well afford to support a wife, but although she liked him she turned him down. Dickens told Miss Coutts later that he asked himself ‘Whether it is, or is not a pity that she is all she is to me and mine instead of brightening up a good little man’s house’, but Georgina, after nine years with the Dickens family, was too much in thrall to his charm and energy to consider any alternative to her position in his life.

28

She was still his pet at twenty-four, but she was a pet with a steely centre, and in the organization of the household her voice was second only to his, and poor ailing Catherine let her rule. Georgy’s adoration flattered him and he flattered her in return, saying she was intellectually far superior to Egg, and that her capacities were greater than those of ‘five out of six’ men.

29

With him she travelled, entertained and was entertained, enjoying an enviable way of life at the side of a great man. The children loved their aunt, but she and Catherine were both regularly required to be at Dickens’s side when he was away from home, leaving the little ones with nurses and governesses and, as the boys grew older, away at boarding school. Georgy cannot have seen much to envy in Catherine’s position: even now she was pregnant yet again, with a tenth child, due in March 1852.

Children at Work

For the next five years Dickens packed so much activity into his life that it is hard to believe there is only one man writing novels, articles and letters, producing

A Child’s History of England

, editing, organizing his children’s education, advising Miss Coutts on good works, agitating on questions of political reform, public health, housing and sewerage, travelling, acting, making speeches, raising money and working off his excess energy in his customary twelve-mile walks. At home, a tenth and last child was born, and Dickens put on ambitious plays for Charley’s birthday at Twelfth Night. All the children had parts, and in 1854 five-year-old Henry Fielding Dickens played in

Tom Thumb

, causing Thackeray to fall off his chair with laughter. The other Home at Shepherd’s Bush was often visited and supervised with meticulous care; he took a close interest in individual young women, and corresponded with Miss Coutts about them and about the many problems of administration. In Wellington Street he presided over

Household Words

with a sharp editorial eye, chivvying Wills with detailed advice by post when away, contributing articles of his own and writing a short novel,

Hard Times

, in weekly instalments to boost circulation in 1854. He travelled about with his theatrical troupe to raise money for the Guild of Literature and Art. When Forster was ill, as he often was, he visited him and read aloud to cheer him. With his newer friends Wilkie Collins and Augustus Egg as travelling companions he revisited Switzerland and Italy. He made occasional dashes to Paris on the twelve-hour South-Eastern railway service, and one long stay there

en famille

. He mourned for three of his men friends, struck down unexpectedly during these years, all in their fifties: Richard Watson, dedicatee of

Copperfield

; the beautiful, Byronic D’Orsay, driven to Paris by his debts; and Talfourd, the ever hospitable playwright and stalwart liberal judge. Also Macready’s wife Catherine, succumbing to the tuberculosis that ravaged her children as well; she was a close friend of Catherine Dickens, who must have missed her badly.

A daguerreotype taken in 1852 shows Dickens clean-shaven, but he made occasional experiments with a moustache and by the summer of 1854 he had settled for one. In 1856 he added a beard, and the fresh-faced Dickens disappeared forever, to the sorrow of Forster, who had invited Frith to paint his portrait just too late to catch him, and of many others too, who thought the bristles hid the beauty of his mouth. His complexion was becoming weather-beaten, his frame lean as ever, his walking habits as vigorous, his pace still a steady four miles an hour.

1

From 1853 the family spent most of their summer holidays in Boulogne, which replaced Broadstairs in his affection. And in December 1853 he read from his Christmas books in Birmingham to audiences of nearly 6,000, and told Wills afterwards that he was ready to consider paid readings. After the last reading on 30 December, Wills wrote, ‘If D does turn Reader, he will make another fortune. He will never offer to do so, of course. But if they

will

have him he will do it, he told me today.’

2

The idea was firmly implanted, although the first paid public reading was not to be until 1858.

Between 1852 and 1857 Dickens wrote three novels which addressed themselves to the condition of England, novels that have endured as accounts of mid-nineteenth-century life and as extraordinary works of art, poetic, innovative, irradiated with anger and dark humour, peopled by lawyers, financiers, aristocrats, bricklayers, circus performers, soldiers, factory-owners, imprisoned debtors and their jailers, child labourers, musicians and dancers, aesthetes, thieves, detectives, committee women, and wives jealous, fierce, tender and battered. There was less laughter than in the earlier books, and more reckoning of accounts, as a man in his forties might think right.

The first of these novels was

Bleak House

. His earliest ideas for the story had been ‘hovering in a ghostly way’ about him since February 1851, but that year, with its deaths, house moving and fund-raising, allowed him no time to settle to a new book, although he was intermittently writing and sometimes dictating to Georgina his

Child’s History of England

.

3

Any thought of starting serious work had to be postponed until they got into Tavistock House, which did not happen until mid-November. Then, within days of sitting down in his new study, he told his publisher Evans there would be a first number of his next novel ready for March 1852. The opening chapters were written in December, and they established at once that the personal themes of

David Copperfield

, attachment and loss, love and friendship, had been left behind for broader and more sombre ones. The scene was set with fog over London and mud underfoot:

London. Michaelmas Term lately over, and the Lord Chancellor sitting in Lincoln’s Inn Hall. Implacable November weather. As much mud in the streets, as if the waters had but newly retired from the face of the earth, and it would not be wonderful to meet a Megalosaurus, fifty feet long or so, waddling like an elephantine lizard up Holborn Hill. Smoke lowering down from chimney-pots, making a soft black drizzle, with flakes of soot in it as big as full-grown snow-flakes – gone into mourning, one might imagine, for the death of the sun … Fog everywhere. Fog up the river, where it flows among green aits and meadows; fog down the river, where it rolls defiled among the tiers of shipping, and the waterside pollutions of a great (and dirty) city. Fog on the Essex marshes, fog on the Kentish heights.

4