Chasing Gold: The Incredible Story of How the Nazis Stole Europe's Bullion (34 page)

Read Chasing Gold: The Incredible Story of How the Nazis Stole Europe's Bullion Online

Authors: George M. Taber

BOOK: Chasing Gold: The Incredible Story of How the Nazis Stole Europe's Bullion

4.47Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Hill and his team arrived at the Lekhaven dock in Rotterdam at 10:30 P.M. It was not the closest one to the central bank office, but it would have been dangerous to try to get any nearer. Nazis now occupied the southern and eastern parts of town and were moving in on the rest. The Rotterdam branch of the Dutch National Bank was located only two hundred yards away from an area the Germans now controlled. Nazi troops had earlier attacked the facility, but Dutch machine gunfire had driven them back.

There were nearly 114 tons of gold still in the Rotterdam bank’s vaults, and the Dutch had hope that they would manage to get all of it out of the country. The immediate British task, though, was to get at least some on

Pilot Boat 19

. During the day of May 10, the bank staff had packed the gold into boxes, and they recruited Dutch marines to help move it. Officials requisitioned four trucks, which marines drove across narrow canal bridges to the bank’s back door, only a short distance away from the heart of the fighting. With just flashlights to guide them, the men went down into the unlit vaults and carried the heavy boxes through darkened halls to the waiting vehicles. Members of an infantry unit also helped with the loading. There still remained just over 102.8 tons in the bank, but that would have to be removed later. From positions on nearby bridges and in trees, German sharpshooters fired at anything that moved.

Pilot Boat 19

. During the day of May 10, the bank staff had packed the gold into boxes, and they recruited Dutch marines to help move it. Officials requisitioned four trucks, which marines drove across narrow canal bridges to the bank’s back door, only a short distance away from the heart of the fighting. With just flashlights to guide them, the men went down into the unlit vaults and carried the heavy boxes through darkened halls to the waiting vehicles. Members of an infantry unit also helped with the loading. There still remained just over 102.8 tons in the bank, but that would have to be removed later. From positions on nearby bridges and in trees, German sharpshooters fired at anything that moved.

Dutch marines then drove the four vehicles toward

Pilot Boat 19

at the Lekhaven dock. Slowly they made their way down dark back streets amid continued shooting. The Dutch had the advantage of knowing their way around Rotterdam’s winding streets and narrow bridges. A half hour later, the small caravan arrived at the boat. The marines unloaded the cargo, which took about two hours to complete. Members of the British demolition unit also helped. The work was tough and progressed slowly because each box weighed more than one hundred pounds, and the men worried about slipping on the narrow gangplank. They finally loaded eleven tons. The bullion was stored near the cabin. They could have taken more, but the captain was worried about the boat’s stability because the weight was mainly on the deck, rather than in the hold. Hill and the boat’s crew set out at 4:45 A.M. for the return trip to the Hook of Holland and the

Wild Swan

, some twenty miles away. There were no other ships on the waterway, so it was a tempting target.

33

Pilot Boat 19

at the Lekhaven dock. Slowly they made their way down dark back streets amid continued shooting. The Dutch had the advantage of knowing their way around Rotterdam’s winding streets and narrow bridges. A half hour later, the small caravan arrived at the boat. The marines unloaded the cargo, which took about two hours to complete. Members of the British demolition unit also helped. The work was tough and progressed slowly because each box weighed more than one hundred pounds, and the men worried about slipping on the narrow gangplank. They finally loaded eleven tons. The bullion was stored near the cabin. They could have taken more, but the captain was worried about the boat’s stability because the weight was mainly on the deck, rather than in the hold. Hill and the boat’s crew set out at 4:45 A.M. for the return trip to the Hook of Holland and the

Wild Swan

, some twenty miles away. There were no other ships on the waterway, so it was a tempting target.

33

At 5:30 A.M., daylight had broken and

Pilot Boat 19

was getting closer to The Hook. The ship had only about another ten miles to go. Just as it approached the city of Vlaardingen, a powerful explosion rocked the whole area. A Nazi magnetic mine that had been dropped into the water after

Pilot Boat 19

had passed the area on its way to Rotterdam blasted the ship into two pieces. Large hunks of wood catapulted into the air, and just six of the twenty-two men on board survived the blast. Most of the crew had been in the ship’s sleeping area below deck. The mine struck the boat two-thirds from the bow, where the gold was stored. One of the survivors was projected across the canal and drowned because he didn’t know how to swim. Workers from a nearby factory rushed to help, but could do little. Willem Pottinga, a crewmember and one of the survivors, was below deck when the explosion occurred and swam to safety dragging the body of a sailor he assumed was dead. He wanted the family to have a chance to bury the man. The person was actually alive, and a doctor resuscitated him. But the gold quickly sank to the bottom of the Nieuwe Waterweg.

Pilot Boat 19

was getting closer to The Hook. The ship had only about another ten miles to go. Just as it approached the city of Vlaardingen, a powerful explosion rocked the whole area. A Nazi magnetic mine that had been dropped into the water after

Pilot Boat 19

had passed the area on its way to Rotterdam blasted the ship into two pieces. Large hunks of wood catapulted into the air, and just six of the twenty-two men on board survived the blast. Most of the crew had been in the ship’s sleeping area below deck. The mine struck the boat two-thirds from the bow, where the gold was stored. One of the survivors was projected across the canal and drowned because he didn’t know how to swim. Workers from a nearby factory rushed to help, but could do little. Willem Pottinga, a crewmember and one of the survivors, was below deck when the explosion occurred and swam to safety dragging the body of a sailor he assumed was dead. He wanted the family to have a chance to bury the man. The person was actually alive, and a doctor resuscitated him. But the gold quickly sank to the bottom of the Nieuwe Waterweg.

At 7:45 A.M., Dutch military authorities informed Lt. Commander Younghusband on the

Wild Swan

that a magnetic mine had blown up

Pilot Boat 19

, killing most of those on board and all the British soldiers.

34

Wild Swan

that a magnetic mine had blown up

Pilot Boat 19

, killing most of those on board and all the British soldiers.

34

On the evening of May 12, Queen Wilhelmina telephoned Britain’s George VI to ask if she could go into exile in his country. As his majesty quipped later, it’s not often that a king gets a phone call from a queen in the middle of the night asking for refuge. The destroyer

HMS Hereward

arrived on May 13 to take Wilhelmina to Britain. When she boarded, the always feisty queen said she wanted to go to Flushing in the southwestern part of the country, where fighting continued. The British captain said that was impossible, so her majesty left for Britain escorted by

HMS Vesper

. Churchill would later say that Wilhelmina was “the only real man among the governments-in-exile in London.” Her ship arrived that same day in Harwich, and she traveled from there by train to London. When she arrived at Liverpool Station, Wilhelmina walked proudly up to the king with a gas mask slung over her shoulder. King George VI greeted her with a kiss on both cheeks.

35

HMS Hereward

arrived on May 13 to take Wilhelmina to Britain. When she boarded, the always feisty queen said she wanted to go to Flushing in the southwestern part of the country, where fighting continued. The British captain said that was impossible, so her majesty left for Britain escorted by

HMS Vesper

. Churchill would later say that Wilhelmina was “the only real man among the governments-in-exile in London.” Her ship arrived that same day in Harwich, and she traveled from there by train to London. When she arrived at Liverpool Station, Wilhelmina walked proudly up to the king with a gas mask slung over her shoulder. King George VI greeted her with a kiss on both cheeks.

35

At 6:00 P.M. on May 13, six British destroyers began the final evacuation of Hook of Holland.

HMS Windsor

rescued members of the Dutch government as well as British, Belgian, Norwegian legation staffs and 400 refugees. Remaining soldiers and citizens continued to fight heroically, to the consternation of the Germans, who still could not believe the Dutch resistance. On May 14, Hitler decided to end the northern offensive quickly. The more important operation aimed at France was due to reach its crucial point in a few days, and he wanted that to stay on schedule. So he sent out War Directive 11, stating coldly, “Political as well as military considerations require that this resistance be broken immediately.” It called for the “rapid reduction of Fortress Holland.” Göring ordered an air bombardment of Rotterdam similar to earlier Nazis attacks on civilian targets in Guernica, Spain and Warsaw, Poland. German planes carpet-bombed the city with 1,150 110-lb. and 158 550-lb. explosives. Huge sections of the town were leveled, and there were immediate reports of 30,000 deaths. The figure was later reduced to about 850. One of the few buildings that survived the Nazi air attack was the Witte Huis, which is still standing proudly in the center of the city today.

36

HMS Windsor

rescued members of the Dutch government as well as British, Belgian, Norwegian legation staffs and 400 refugees. Remaining soldiers and citizens continued to fight heroically, to the consternation of the Germans, who still could not believe the Dutch resistance. On May 14, Hitler decided to end the northern offensive quickly. The more important operation aimed at France was due to reach its crucial point in a few days, and he wanted that to stay on schedule. So he sent out War Directive 11, stating coldly, “Political as well as military considerations require that this resistance be broken immediately.” It called for the “rapid reduction of Fortress Holland.” Göring ordered an air bombardment of Rotterdam similar to earlier Nazis attacks on civilian targets in Guernica, Spain and Warsaw, Poland. German planes carpet-bombed the city with 1,150 110-lb. and 158 550-lb. explosives. Huge sections of the town were leveled, and there were immediate reports of 30,000 deaths. The figure was later reduced to about 850. One of the few buildings that survived the Nazi air attack was the Witte Huis, which is still standing proudly in the center of the city today.

36

At dusk that night, General Winkelman, the commander of the Dutch military, ordered his troops to stop fighting. The next morning at 10:00, German and Dutch officers signed a capitulation order.

37

37

Under the Dutch-German armistice agreement, the Dutch were charged with cleaning up the country’s many waterways, which were now cluttered with the flotsam and jetsam of the invasion. German officials at the time knew nothing about the gold resting at the bottom of the Nieuwe Waterweg. The Netherlands National Bank on June 1, signed a contract with a salvage company to search the area where the pilot boat had sunk. Divers pulled up 75 bars on the first day of the rescue operation and 169 on the second. They were all turned over to the Rotterdam bank. A month later, a German merchant who had a shop nearby told the new Nazi harbor commander in Rotterdam about the golden

Pilot Boat 19

disaster. The Dutch by then had salvaged about 750 bars. A German court ruled that the gold belonged to the Reich. In October 1940, the Dutch Central Bank said in view of that they were not going to continue the salvage operation. By then they had found 816 bars.

Pilot Boat 19

disaster. The Dutch by then had salvaged about 750 bars. A German court ruled that the gold belonged to the Reich. In October 1940, the Dutch Central Bank said in view of that they were not going to continue the salvage operation. By then they had found 816 bars.

After the war, the Nieuwe Waterweg was deepened and expanded; and during that work more gold bars were uncovered and local workmen got some of the treasure. Six bars have never been accounted for and might have been stolen. In any case, they were never found. The channel is today much deeper than it was in 1940, and no one believes that any gold remains at the bottom of the waterway.

38

38

After the Nazis consolidated their hold on the country, they began sending the gold left at the Rotterdam branch to Berlin. The first shipment of 536 bars weighed 6.7 tons. Six more shipments were later made, with the last one departing on October 18, 1943. During the next two years, the Dutch shipped 192.7 tons of gold to Berlin.

In the Netherlands, as in other occupied countries, the Nazis captured privately held gold. Dutch citizens were forced to sell their bullion coins and small bars to the Dutch central bank, which paid them in guilders. The bank had to pass them along to Berlin. The Dutch, instinctively law-abiding people, complied with few protests. Citizens sold 35.5 tons of gold to the state bank.

Germany’s

Devisenschutzkommandos

were also active in collecting private Dutch gold and other valuables held in private banks. With a bank employee always present, they opened every safety deposit box in the country. The process took a year to complete and resulted in a haul of nearly ten tons of gold bars plus ƒ4.2 million in gold coins and millions more in American, French, Swiss, Belgian, and German currency. All that private wealth was handed over to Göring’s Four Year Plan, but was stored at the Reichsbank.

39

Devisenschutzkommandos

were also active in collecting private Dutch gold and other valuables held in private banks. With a bank employee always present, they opened every safety deposit box in the country. The process took a year to complete and resulted in a haul of nearly ten tons of gold bars plus ƒ4.2 million in gold coins and millions more in American, French, Swiss, Belgian, and German currency. All that private wealth was handed over to Göring’s Four Year Plan, but was stored at the Reichsbank.

39

As the war dragged on, the Nazis found new ways to confiscate Holland’s remaining gold and foreign currency. On March 24, 1941, Arthur Seyss-Inquart, the Austrian Nazi who became

Reichskommissar

of Holland, demanded that the country pay 500 million Reichsmark for so-called occupation costs. For starters, ƒ75 million had to be paid within two weeks in gold. The Dutch eventually sent ƒ1.2 billion per year to Berlin as occupation payments for the entire war.

Reichskommissar

of Holland, demanded that the country pay 500 million Reichsmark for so-called occupation costs. For starters, ƒ75 million had to be paid within two weeks in gold. The Dutch eventually sent ƒ1.2 billion per year to Berlin as occupation payments for the entire war.

Starting in March 1942, Berlin also demanded that the Netherlands help pay for the cost of Germany’s invasion of the Soviet Union. This was called their contribution to the “fight against Bolshevism.” The allotted Dutch amount was 50 million Reichsmark per month, with 10 million of that paid in gold. Since the invasion of the Soviet Union had started nine months earlier, the initial installment was 90 million Reichsmark in gold.

Central Bank President L.J.A. Trip resigned in protest to Nazi policies in March 1941, but the Germans simply replaced him with a compliant successor, Meinoud Rost van Tonningen, a leader of the Dutch Nazi party and also secretary-general of the finance ministry. In March 1943, he sent a message to Seyss-Inquart that virtually all the treasure that had been left in the vaults or in private accounts was now in Berlin.

Small amounts of gold were found in December 1944 and February 1945 in regional central bank offices in Arnhem and Meppel. In Arnhem the Nazis discovered 32 bags of gold coins that weighed a little less than one ton, and in Meppel they got 1.4 tons. The Arnhem gold went directly to Berlin, but that in Meppel did not because the Germans thought the Soviets would confiscate it when they reached Berlin. It went instead to the regional Reichsbank branch in Würzburg in Bavaria. The last Dutch gold arrived in Germany on February 26, 1945.

The Dutch lost a total of 145.6 tons of gold to the Nazis, the second largest amount of any nation after Belgium. That consisted of 104.9 tons taken from central bank vaults, 28.8 tons robbed from the public, 9.6 tons from

Pilot Boat 19

, and 2.3 tons from Arnhem and Meppel. The valiant Dutch and British efforts under the most dangerous and difficult circumstances possible succeeded in saving 70.6 tons.

40

Pilot Boat 19

, and 2.3 tons from Arnhem and Meppel. The valiant Dutch and British efforts under the most dangerous and difficult circumstances possible succeeded in saving 70.6 tons.

40

Chapter Sixteen

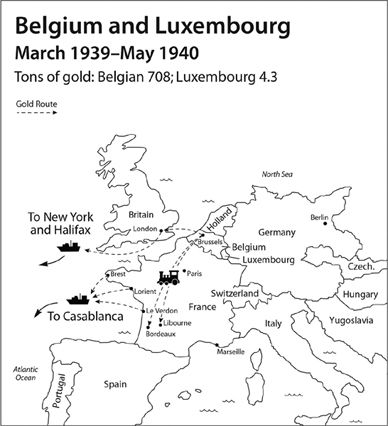

BELGIUM AND LUXEMBOURG TRUST FRANCE

Throughout history Belgium has been Western Europe’s bloody crossroads. During the Middle Ages it was one of the world’s richest regions and a major center of the industrial revolution. Unfortunately, it has also been the region where the Germanic and Latin cultures collided and fought brutal wars. Wellington defeated Napoleon at Waterloo just outside of Brussels. Armies of Germany, France, and Britain in World War I, fought to a stalemate there, and as the poem recounts, “In Flanders Fields the poppies blow/Between the crosses, row on row.”

Belgium has been a nation state only since 1830, when its often-quarrelsome citizens in the two regions of Wallonia and Flanders united just long enough to throw out their Dutch rulers. In that era Britain was a superpower, and London guaranteed Belgium’s independence and neutrality as well as that of Luxembourg, its neighbor to the southeast. The Belgians, though, selected Leopold from the House of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha in Germany to be the first King of the Belgians. The new country was an uneasy mixture of Catholics and Protestants, industrialists and farmers, and Flemish and French speakers. It regularly suffered through recurring political crises, and between June 1936 and September 1939, Belgium had six different governments struggling unsuccessfully to deal with both an economy that had not recovered from World War I and the rise of Nazi power next door. The young Leopold III believed staunchly that the country’s neutrality was its only hope for escaping a repetition of World War I, while Belgian politicians mostly looked to London and Paris for protection.

The Grand Duchy of Luxembourg is a small and hilly agrarian country located at the spot where France, Belgium, and Germany meet that had a population in 1940 of about 300,000. Powerful neighbors had often overrun the country. Celts and Romans as well as France, Poland, Spain, Austria, Holland, Belgium and Prussia have at times ruled the tiny nation. During World War I, it tried to be neutral, but German troops occupied it. Nevertheless, Grand Duchess Marie-Adélaïde remained with her people in her country during that entire conflict.

Other books

Los límites de la Fundación by Isaac Asimov

No Time Like the Present: A Novel by Gordimer, Nadine

The Sinister Signpost by Franklin W. Dixon

Cape Fear by John D. MacDonald

Awaken to Pleasure by Lauren Hawkeye

No Laughing Matter by Carolyn Keene

In the Life by Blue, Will

Magic Seeds by V.S. Naipaul

In a Dry Season by Peter Robinson

Premio UPC 2000 by José Antonio Cotrina Javier Negrete