Chasing Gold: The Incredible Story of How the Nazis Stole Europe's Bullion (31 page)

Read Chasing Gold: The Incredible Story of How the Nazis Stole Europe's Bullion Online

Authors: George M. Taber

BOOK: Chasing Gold: The Incredible Story of How the Nazis Stole Europe's Bullion

11.38Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Count Galeazzo Ciano, Mussolini’s son-in-law and foreign minister, took the lead within the Rome government in advocating an invasion of Albania. Ciano also promised Mussolini great mineral resources in the undeveloped country, although he had little research to back that up. The Italian leader, though, was a reluctant warrior, and Italy’s Albanian adventure eventually became largely Ciano’s war.

6

6

The count hoped that the king would be slow to fight because of his concern for the impending arrival of an heir to his throne. Zog in April 1938 married Géraldine Apponyi de Nagy-Appony, a half American and half Hungarian princess, in a lavish wedding. Count Ciano attended the ceremony, and Hitler sent a red Mercedes as a wedding present. Queen Geraldine’s main job was to provide the new kingdom with an heir, and she was soon pregnant. Ciano believed the pregnancy would be a distraction and keep the king’s mind off politics, writing in his diary, “There is, above all, an act on which I am counting: the coming birth of Zog’s child. The king loves his wife very much, as well as his whole family. I believe that he will prefer to insure to his dear ones a quiet future. And frankly I cannot imagine Geraldine running around fighting through the mountains of Unthi or the Mirdizu in her ninth month of pregnancy.”

7

7

Zog sensed that the Italians might cause trouble and tried to recruit allies, but he had little success. Britain’s Neville Chamberlain showed no interest in standing up to the Nazis. The United States was trying to stay out of all foreign commitments despite recent German aggression. Neither Greece nor Yugoslavia was about to offer any help to their former enemy.

In December 1938, Count Ciano presented an invasion plan to Mussolini. The Italian leader tentatively approved it, but did not set a date for its implementation. Zog soon got wind of the danger, and in March of 1939 sent a message pleading, “Albania now is in Italy’s hands, for Italy controls every sector of the national activity. The king is devoted. The people are grateful. Why do you want anything more?” Zog also sent a request for help to Hitler, but received no sympathy.

8

8

By late March and after the Germans had overrun both Austria and Czechoslovakia, Mussolini drew up an eight-point list of demands that was sent to Zog. It included giving Italy access to all of Albania’s ports, airports, and communication facilities. Albania would have become a vassal state totally under Italy’s control. Zog might survive, but only as a puppet king. It was clear that failure to implement the demands would be the grounds for an invasion, and likely a brutal one at that for a small nation still recovering from war.

9

9

Zog immediately began playing for time and told Ciano that he was willing to go along with the demands, but said that his government was refusing. The Italians at that point concluded that it was going to be impossible to browbeat the king into capitulation, and so Italian troops prepared to invade. Marshal Pietro Badoglio, the country’s military leader and the hero of the invasions of Libya and Ethiopia, opposed the move, but other Italian generals were willing to go along. A new demand was then set to King Zog, with the warning that if he did not accept it the Italians would invade on April 7. Mussolini this time sent his own personal ultimatum.

10

10

The Italians purposely did not consult Hitler on any of their moves against Albania. Mussolini and Ciano were not really interested in any peaceful solution with Albania. They wanted to show Hitler their country’s military might in order to have a more powerful hand in European politics. Ciano wrote in his diary on April 4 that Il Duce “would prefer a solution by force of arms.”

11

11

On April 5, Her Majesty Queen Geraldine gave birth to a son, who was named Crown Prince Leka. The king ordered a 101-gun salute. The Albanian royal family now had its heir. The king asked the U.S. minister in Tirana, Hugh Grant, whether mother and child could obtain political asylum in America. The U.S. agreed. The birth had been complicated, but the queen still received a doctor’s permission to travel, and so she and her two-day old son headed south toward Greece.

12

12

Shortly after seeing his heir, Zog received a new ultimatum from Rome. He also learned about the attitude of the British toward the Italian-Albania situation. Prime Minister Chamberlain in response to a question in Parliament on whether Britain had any interest in Albania said, “No direct interest, but a general interest in the peace of the world.” He then left for a week of fishing in Scotland. Ciano was pleased.

13

13

The Italian invasion began on April 7 at 5:00 A.M. and met virtually no resistance. Zog wanted to retreat into the hills and lead a guerilla fight against the Italians, but the Albanian parliament told him to leave the country. The Italian offensive turned into something of a circus fire drill. The invading force consisted of twenty-two thousand men and four hundred planes, three hundred small tanks, and a dozen warships. The Albanians had about four thousand poorly trained soldiers and a few policemen. Yet in the port city of Durres, locals and a few soldiers drove the first invaders back into the sea. The Italians, though, successfully landed in a second attempt. The capital of Tirana fell at 10:30 A.M. on the day of the invasion without a shot being fired. Historian Bernd Fischer wrote, “The bungled invasion did the fascist leadership a great service; it made clear to them how totally unprepared Italy was to fight a major war.”

14

Count Ciano, though, triumphantly flew his own plane to the capital of Tirana, where he found the streets empty.

14

Count Ciano, though, triumphantly flew his own plane to the capital of Tirana, where he found the streets empty.

King Zog went on the radio at 2:00 in the afternoon to make a brave appeal for national unity and resistance, saying, “I invite the whole Albanian people to stand united today, in this moment of danger, to defend the safety of the country and its independence to the last drop of blood.” The only trouble was that Albania at the time had less than two thousand radios, and the Italians soon jammed the airways.

15

15

Not long after giving the speech, the king left and the following afternoon he arrived in Florina, a small town in northern Greece. Italian radio claimed that he had stolen 550,000 gold francs from the central bank before leaving. The British foreign office later learned that Zog had £50,000 in gold as well as $2 million in a Chase Manhattan Bank account. Whatever he had was enough to pay for a long life in exile. He and his wife and child traveled first to France and then to Britain. After the war he ended up in Egypt as the guest of King Farouk. Rumors were that Zog paid him $20 million for that refuge.

16

16

In the years leading up to the war, the Albanian Central Bank, which was largely under the influence of Italian bankers, had been shipping its gold to the Bank of Italy in Rome for safekeeping. By the time Mussolini’s forces invaded, the vast majority of it was already in Italy, and the ownership was turned over to the Bank of Italy after the fall of Zog. That amounted to eight million gold francs weighing in at 2.4 tons. The Italians got only 280 gold francs when they took over the Albanian Central Bank in Tirana plus five million more in coins and jewelry from residents.

17

17

Following the Allied invasion of Italy in September 1943, the Italians ousted Mussolini, but the soon Nazis put him back in power. On April 16, 1944 Berlin ordered Albanian officials to sign a protocol giving the Germans fifty-five cases of gold that had been stored at the Bank of Italy. They were sealed with steel strips and stored in secret tunnels. Germany military units near the end of that year picked up both the Italian and Albanian central bank gold and sent it to the Reichsbank in Berlin. It remained there until February 1945, when it was evacuated with other seized Nazi gold and art treasures to the salt mine in Merkers, Germany.

18

18

Chapter Fifteen

HOLLAND FALLS IN FOUR DAYS

The period between the fall of Poland in October 1939 and the invasion of Western Europe in May 1940 has gone into history with many names. It was a time of peace, but the world was waiting anxiously for more war. Americans called it the Phony War; the French named it the

drôle de guerre

(funny war); Churchill deemed it the Twilight War; and to cynics it was the

Sitzkrieg

(sitting war) or the Bore War. Semantics aside, Hitler, after securing his truce with Russia in the east, used the next few months to prepare a major military offensive in the west.

drôle de guerre

(funny war); Churchill deemed it the Twilight War; and to cynics it was the

Sitzkrieg

(sitting war) or the Bore War. Semantics aside, Hitler, after securing his truce with Russia in the east, used the next few months to prepare a major military offensive in the west.

Originally Nazi generals planned to invade Western Europe in November 1939, with a war strategy similar to that of World War I. Hitler was not too happy with the plan, considering it insufficiently daring. Then on January 10, 1940, that document accidently fell into Allied hands. German regulations forbade officers from taking secret papers on flights near enemy or neutral territory. But as we now know, the newly wed major who was ordered to take the war plans between two locations in Germany, went by plane instead of train so that he could spend an extra night with his bride. And thus the Allies were able to get a hold of the invasion plans via the Belgians who intercepted the major’s lost aircraft. Hitler was not all that unhappy because he had never liked the original proposal.

1

1

General Erich von Manstein, perhaps the most brilliant strategist of World War II, provided exactly what the Führer wanted. The general came from a long line of officers and at the time was chief-of-staff of General Gerd von Rundstedt, the commander of Army Group I. Manstein supported the new ideas of General Heinz Guderian, who had studied the intra-war work on tank warfare done by Britain’s J. F. C. Fuller and B. H. Liddell Hart as well as France’s Charles de Gaulle. Army Chief of Staff Franz Halder originally opposed Manstein’s proposal, and Hitler first heard about it from his chief adjutant. On February 17, 1940, he had a working breakfast with newly appointed corps commanders, a group that included Manstein. He so impressed Hitler that the Führer kept him until 2:00 P.M. to discuss his ideas in detail.

2

2

Manstein’s revised plan, which was ready only a week later, was codenamed Case Yellow. It broke the western offensive into northern and southern operations. The two would start simultaneously. The northern one against Holland and northern Belgium had to be a fast and crushing operation because that would be just a setup for the more important southern offensive. This would be a surprise thrust through Luxembourg and southern Belgium before German forces attacked northern France at Sedan on the Meuse River. The genius of the plan, which Hitler modified some and actually improved, was a tank attack through the Ardennes forest, which was then considered to be a natural barrier to an invasion. The boldness and heavy use of armored vehicles greatly appealed to Hitler. The plan now had the name

Operation Sichelschnitt

(Cut of the Sickle). Hitler also called in Guderian to ask him what he would do when he reached Sedan, and the tank enthusiast said he would drive right to the English Channel. That, though, was too bold for Hitler and the top military brass, and a final decision on that part was put off until later.

3

Operation Sichelschnitt

(Cut of the Sickle). Hitler also called in Guderian to ask him what he would do when he reached Sedan, and the tank enthusiast said he would drive right to the English Channel. That, though, was too bold for Hitler and the top military brass, and a final decision on that part was put off until later.

3

After officials at

De Nederlandsche Bank

(The Netherlands National Bank) learned how the Nazis had captured the national bank gold when they invaded Austria and Czechoslovakia, they began looking for ways to protect their own holdings, which were among the largest in the world. As an historic financial center and global trader, Holland traditionally had large amounts of bullion in its vaults. Dutch military leaders repeatedly told political leaders that they could protect it over the years, and so they became complacent, figuring that even if there were an invasion they would have time to evacuate the gold via the country’s many ports. Nonetheless, central bank officials discussed various ways of protecting it, including the possibility of storing the metal in one of the country’s famous polders, the low-lying land behind the dikes.

4

De Nederlandsche Bank

(The Netherlands National Bank) learned how the Nazis had captured the national bank gold when they invaded Austria and Czechoslovakia, they began looking for ways to protect their own holdings, which were among the largest in the world. As an historic financial center and global trader, Holland traditionally had large amounts of bullion in its vaults. Dutch military leaders repeatedly told political leaders that they could protect it over the years, and so they became complacent, figuring that even if there were an invasion they would have time to evacuate the gold via the country’s many ports. Nonetheless, central bank officials discussed various ways of protecting it, including the possibility of storing the metal in one of the country’s famous polders, the low-lying land behind the dikes.

4

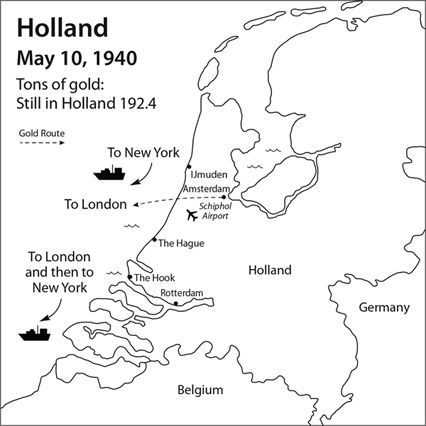

A new cabinet was more realistic about the Nazi threat, however, especially in light of what was happening to their eastern neighbors, and the central bank began quietly shipping large amounts of bullion out of the country, primarily at first to Britain, the world’s traditional storage destination and a nation with which Amsterdam had strong historic ties. At the time, the Dutch Central Bank owned 555.8 tons. Later the Dutch also sent bullion to the Federal Reserve in New York, which now looked to be safer than London. In September 1938, Central Bank President L.J.A. Trip confidentially told the country’s prime minister and minister of finance that Holland had ƒ546 million guilders of its gold abroad, with seventy-five percent in Britain and twenty-five percent in the U.S. When the Germans attacked Holland, the Dutch had more than eighty percent of its bullion at the New York Federal Reserve. The central bank, though, still had 192 tons in the country on the day of the invasion.

5

5

In November 1939, Dutch officials received news from German opposition sources that Hitler was making plans to invade Holland as part of his plan to conquer Western Europe. The Dutch Central Bank staff at the main office in Amsterdam then hurriedly packed up ƒ125 million in gold bars and ƒ41 million in coins, so they would be ready to move on short notice. It was stored in the basement of its three-story building constructed in 1868 that stood amid gabled mansions in the city center on a street named Oude Turfmarkt. A small circular railroad track provided quick and easy access, and the national treasure could make a quick departure via canal. The plan was that it would go by small boat through the canal to the North Sea, and there would be loaded on bigger ships. While that storage facility was quaint and historic, the Dutch had more of its bullion stored at its more modern branch office in Rotterdam, forty-five miles south. The central bank still had 192.4 tons of gold in the country, with one-third in Amsterdam and two-thirds in Rotterdam. That amounted to thirty-five percent of its total holdings.

6

6

Other books

In His Dreams by Gail Gaymer Martin

The Last Madam: A Life in the New Orleans Underworld by Chris Wiltz

Circles of Seven by Bryan Davis

Margaret Moore - [Warrior 13] by A Warrior's Lady

Linda Goodman's Sun Signs by Linda Goodman

Dinero fácil by Jens Lapidus

Purple Golf Cart: The Misadventures of a Lesbian Grandma by Ronni Sanlo

The Troubles by Unknown

Kitt Peak by Al Sarrantonio

Cartagena by Nam Le