Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World (44 page)

Read Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World Online

Authors: Samantha Power

BOOK: Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World

10.54Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

On May 18 his UN team left Belgrade and embarked upon an investigation that would take them almost nineteen hundred miles in eleven days. They traveled in a fleet of ten white Toyota 4Runners, each marked with a large black “UN” logo. Terry Burke, the UN head of security for the mission, brought a separate stack of large black UN decals and plastered one to the roof of each of the cars. “I don’t want to get blasted for an error,” Burke

told Vieira de Mello. “If we get hit, I want everyone to know that whoever hit us did so

because

we are the UN.” The UN convoy was led and trailed by a Serbian police car. Burke had attempted to draft a getaway contingency plan, but he had just ended up with question marks. “Getaway where? With what?” he had asked himself. “If you run away from the Serb paramilitaries on the main roads, then you end up on the side roads vulnerable to NATO bombers.”

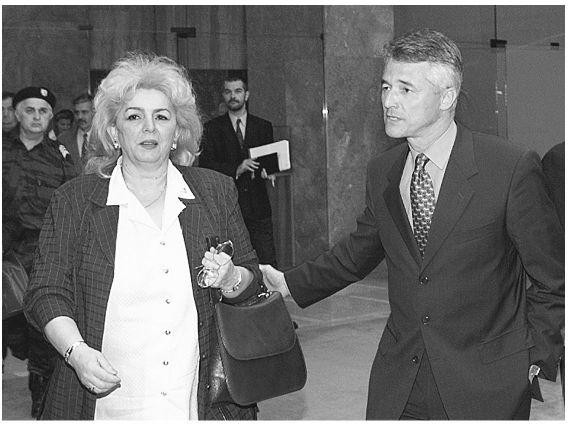

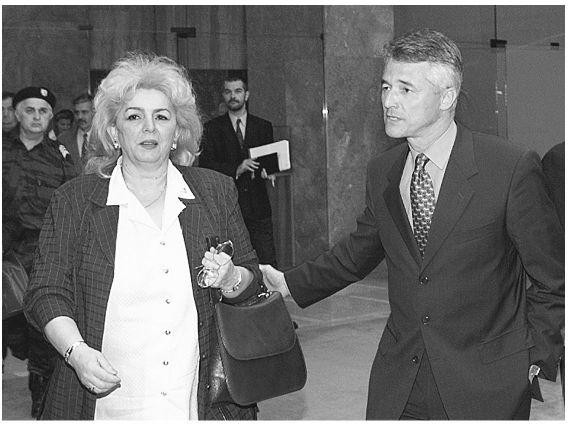

Vieira de Mello and Yugoslav minister of refugees Bratislava Morina, May 1999.

because

we are the UN.” The UN convoy was led and trailed by a Serbian police car. Burke had attempted to draft a getaway contingency plan, but he had just ended up with question marks. “Getaway where? With what?” he had asked himself. “If you run away from the Serb paramilitaries on the main roads, then you end up on the side roads vulnerable to NATO bombers.”

The first stop on the UN tour was the Chinese embassy in Belgrade, which had been struck eleven days before. When the UN team reached the ruins of the building, Vieira de Mello shook his head in disbelief at the sight before him: The attack had blown a six-foot-deep crater out of one side of the building and a pair of gaping holes out of the other side. One of the walls seemed to have been peeled off, revealing, like the exposed interior of a dollhouse, the desks, bookshelves, couches, and artwork of the embassy, which, though covered in a thin layer of dust, remained intact. “NATO is precise all right,” Vieira de Mello muttered to a colleague. “They just hit precisely the wrong target.”

It had not been easy to find drivers willing to transport a UN delegation into a three-way battlefield. UN policemen who worked in neighboring Bosnia had lent themselves to the mission, but this meant that the drivers of the vehicles were not professional drivers and were not from the region. (The full-time drivers in Bosnia were natives of the area and thus could have become targets.) Already two of the UN cars in what had originally been a twelve-vehicle fleet had failed to show after getting lost on the drive up from Sarajevo.

After leaving the Chinese embassy, the driver of Vieira de Mello’s lead vehicle suddenly noticed that the rest of the convoy was no longer visible in the rearview mirror. Once their car turned around and drove a mile back up the road, Vieira de Mello saw an overturned UN 4Runner on the horizon. Horrified, he pieced together what had occurred. The route was heavily trafficked because NATO had bombed several of the major roads. A Serb driver had become so transfixed by the sight of ten white UN vehicles speeding toward him on the other side of the road that he did not notice until the last minute that the traffic in front of him had stopped. Instead of ramming the car in front of him, he had swerved into the oncoming traffic, where a Ghanaian UN policeman was zooming toward him recklessly at close to eighty miles per hour. In order to avoid a head-on collision, the Ghanaian had jerked his car toward the side of the road. As he did, he lost control of the vehicle, which flipped in the air, hit a tree, and landed upside down in a ditch.

Bakhet, who was traveling in the car directly behind the vehicle that crashed, had only looked up in time to see a large white vehicle flying through the air, for seemingly no good reason. Although he had given up smoking, he was so shaken that he asked for a cigarette, then nervously joined in the team’s effort to remove the injured UN officials from the wreckage. His cigarette hung precariously out of his mouth as diesel trickled slowly out of the car’s tank and out of jerry cans in the trunk.

The men pulled out of the vehicle were Nils Kastberg and Rashid Khalikov, who had led the advance mission to Belgrade the week before. Trembling and pale on the side of the road, Khalikov had multiple fractures in his upper left arm and lower back. He shouted, “My mobile, give me my mobile.” He wanted to call his wife. Kastberg was also disabled with multiple fractures to his right foot.

Vieira de Mello rushed between Kastberg and Khalikov. He instructed the Yugoslav security services to call an ambulance and turned to David Chikvaidze, an aide whose job it was to maintain contact with NATO headquarters. “Tell them that we have two men down,” he said, “and to go easy on the bombing around Belgrade hospitals.”

Nothing seemed to be going according to plan. NATO had refused to guarantee the security of the mission. The Serbs had routed the delegation away from the terra incognita of Kosovo to towns in Serbia proper, where Western journalists were already present in droves. And finally, no sooner had the UN convoy left Belgrade and begun the journey into the countryside than it had been felled by a serious road accident. “I can see the Serbian papers tomorrow,” Vieira de Mello quipped. “A photo of one of our cars in the

ditch, and the caption, ‘Beware, the UN has arrived!’ ” Most team members had the same reaction as they took in the scene, saying to themselves, out loud or in their heads, “Classic UN!”

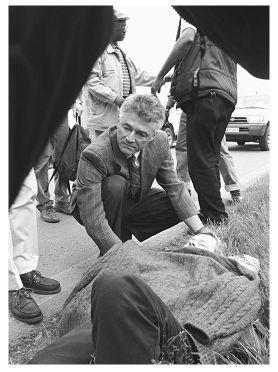

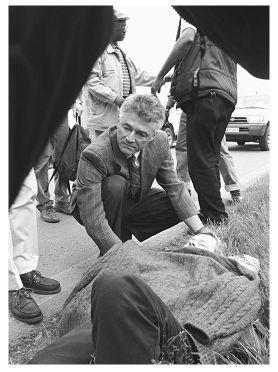

Vieira de Mello comforts an injured Nils Kastberg of UNICEF.

Once Kastberg and Khalikov had been bundled off to the hospital, Vieira de Mello set about comforting the other team members. Kirsten Young, who had been ambivalent about joining the UN team to begin with, was asking herself, “What the hell am I doing here? We have no idea what we’re doing!” As Young remembers, “You fear you are going to get bombed, but instead of getting bombed, you have a car crash completely of your own making.” Dr. Stéphane Vandam, the WHO representative on the team, had helped organize the medical evacuation. He too began to wonder whether they were in over their heads. “We were standing up for humanitarian values, putting them back in the hands of Kofi Annan, and taking them away from the politicians,” he remembers. “It was a brave mission, but it began then to feel like a very stupid mission.” After the accident Vieira de Mello went out of his way to give off an almost exaggerated air of confidence.Young recalls,“I was terribly frightened. I didn’t trust our drivers, I didn’t trust our security guys, and I didn’t trust the Serbs or NATO. Yet every time I looked up and saw Sergio smiling, I thought to myself, ‘If Sergio is here, it’ll be okay.’ He was a Teflon guy in the sense that nothing bad seemed to touch him.”

The delegation continued onward to the town of Novi Sad, in the Serbian province of Vojvodina. There they saw the Sloboda (Freedom) bridge collapsed in the Danube River. It was the second of Novi Sad’s three bridges hit in the early days of the NATO air campaign. Confronted with the hysteria and rage of Yugoslav authorities and Serb civilians, Vieira de Mello tried to argue that the UN had not authorized the war and that it and NATO were distinct entities. His hosts were unpersuaded. After the UN delegation had concluded a meeting with one Serbian town mayor, Chikvaidze spotted a poster on the door to the city hall with an image of a skull capped by a UN helmet, and he asked a burly Serb guard in the lobby of the building whether he could take the poster with him.The guard shrugged a grudging acceptance, as if to say, “Everything is now possible in my country.” Vieira de Mello shook his head when he saw the poster. “That is the predicament the UN is in,” he said.“What the Serbs are saying with that poster is, ‘The UN is no better than NATO. Because you didn’t stop NATO from doing this, you are all the same.’ ” When Vieira de Mello would go to Iraq in 2003, many would similarly blame the UN for failing to stop the U.S.-led invasion.

Vieira de Mello was alternately impressed and horrified by NATO’s aim. While he talked to villagers in one southern Serbian city, he heard a whistling sound and looked up to see a cruise missile flying through the sky. “Wow,” he exclaimed with boyish wonderment as the missile crashed in the distance. “Thank you, General Electric, for not screwing that one up.” Ten miles down the road, the mission encountered the burning ruins of a Serb police station that the missile had struck.

Just before the UN team sat down to a dinner hosted by officials in Niš, Yugoslavia’s third-largest city, the Serbian government host presented Vieira de Mello with photographs of the cadaver of a pregnant woman who he claimed had been killed by a NATO strike.The Serb official ended his presentation by circulating pictures of a destroyed fetus. Vieira de Mello was disgusted by the images, but he was just as outraged by the Serbs’ willful exploitation of the carnage. A Serbian reporter asked him about the photographs he had seen. “They’re deplorable,” he said sternly. But he added, “I’ve told you what I think you need to do to stop that.”

7

He knew that once he reached Kosovo, he was likely to find many such gruesome scenes—the victims of Serbian ethnic cleansing.

7

He knew that once he reached Kosovo, he was likely to find many such gruesome scenes—the victims of Serbian ethnic cleansing.

Throughout the trip he remained concerned about the fates of Kastberg and Khalikov, who were sharing a room in the intensive care unit of Belgrade Central Hospital. In solidarity with the mission, the men had refused to be evacuated back to Geneva and had undergone surgery in Belgrade. Vieira de Mello thus had to worry not only about the safety of the personnel in his convoy but also about them. Nonetheless, he was personally moved by their courage and loyalty, and knowing that they were crestfallen to have been sidelined after planning the trip, he telephoned them nightly in order to keep them in the loop. “He would tell us exactly what the mission had done that day,” Khalikov remembers. “He wanted to show us we were still part of the team.” Each night when Vieira de Mello checked in with the men, he could hear the crash and thud of bombs landing nearby. “We both knew that if something went wrong, we wouldn’t be able to run,” recalls Khalikov. “I was lying flat. I couldn’t get up. Nils couldn’t walk.” The men had also been warned upon arrival that a likely NATO target, the ministry of the interior, was located nearby. Although NATO had been given the coordinates of the hospital, the men had seen the wreckage of the Chinese embassy and knew that deadly mistakes were possible. Kastberg assured Vieira de Mello that the morale of the two patients was high. “Between us, we have three legs and three hands,” he said, “but we are in the hands of gorgeous nurses!”

On May 20 Vieira de Mello’s UN convoy finally entered the province of Kosovo, which appeared to have been emptied of ethnic Albanians. He was relieved finally to be on the most important leg of the trip. “I want to be able to move freely,” he told a reporter. “I don’t want any more speeches.”

8

As the UN vehicles trundled into the province, men at the roadside shouted “Serbia! Serbia!” and offered the three-fingered Serbian salute.The UN team was now vulnerable to attack from three sides; armed Serbs, NATO, and the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) were all engaged in fighting.

8

As the UN vehicles trundled into the province, men at the roadside shouted “Serbia! Serbia!” and offered the three-fingered Serbian salute.The UN team was now vulnerable to attack from three sides; armed Serbs, NATO, and the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) were all engaged in fighting.

The three UN security officials on the trip were not carrying guns, so the team had no choice but to rely on their police escorts for protection. These Serb “minders” were not about to let UN officials move around as they wished. Several times when Vieira de Mello tried to visit villages off the main roads, they refused, claiming the areas were unsafe. As the convoy progressed, the UN team encountered columns of ethnic Albanians fleeing on tractors or on foot. They saw houses, apartments, and shops that had been systematically burned or looted. Anti-Albanian and pro-Serb slogans had been painted on newly vacated buildings. In some areas 80 percent of the homes had been torched. On two occasions the team members themselves witnessed houses being set ablaze.

Other books

Twisted Metal by Tony Ballantyne

Texas Outlaws: Billy by Kimberly Raye

Moth to the Flame by Sara Craven

cowboysdream by Desconhecido(a)

18th Abduction (Women's Murder Club) by James Patterson

These Foolish Things by Thatcher, Susan

Sarai (Jill Eileen Smith) by Jill Smith

Reasons of State by Alejo Carpentier

Nobody Likes Fairytale Pirates by Elizabeth Gannon