Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World (80 page)

Read Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World Online

Authors: Samantha Power

BOOK: Chasing the Flame: Sergio Vieira de Mello and the Fight to Save the World

12.65Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

Back in New York, Tun Myat was not the first to learn of the attack. At 8:32 a.m. (4:32 p.m. Baghdad time) Kevin Kennedy, the former U.S. Marine and senior humanitarian official who had only left Baghdad on July 28, got out of the elevator on the thirty-sixth floor in New York and saw that he had a message on his cell phone. Bob Turner had called him just after the attack. “Car bomb, car bomb, Canal Hotel, Canal Hotel,” Turner had shouted into Kennedy’s voice mailbox. Kennedy called the UN operations room, but they had not yet heard about any bomb. Kennedy next called the thirty-eighth floor so that the secretary-general, who was on vacation with his wife on a small island off the coast of Finland, could be informed. He then sprinted the length of the corridor to find an office with a television set. CNN was showing nothing on the attack, so Kennedy hoped Turner’s message might have overstated the case. But at 9:01 a.m., thirty-three minutes after the blast, Kennedy’s face sank as CNN broadcast a “breaking news” item from Baghdad. UN headquarters in Iraq had been struck by a car bomb.

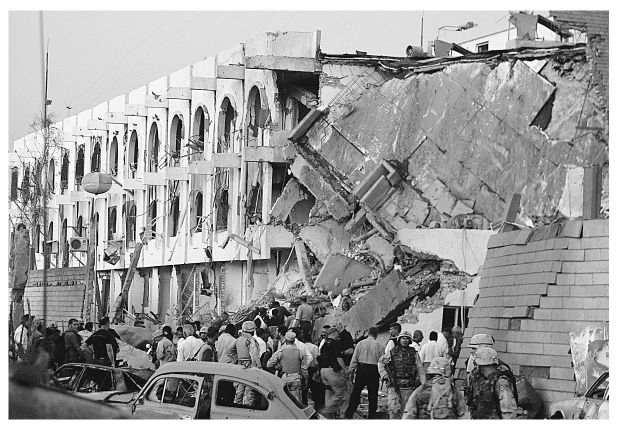

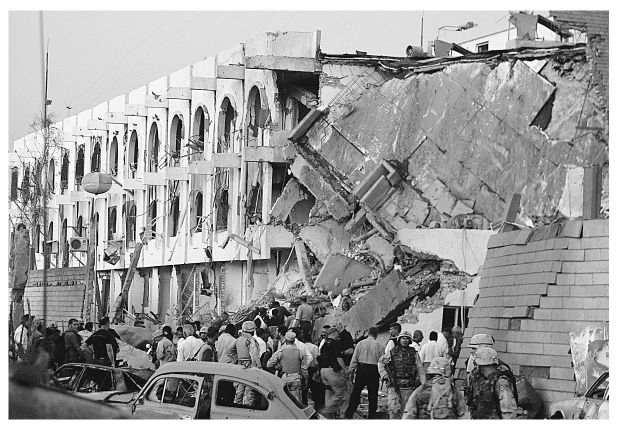

Information was spotty. Within minutes of the attack, U.S. soldiers from the Second Armored Cavalry Regiment had begun to cordon off the hotel, preventing CNN’s correspondent, Jane Arraf, from reaching the complex. But CNN did have a crew on the scene who at the time of the blast had been filming a press conference on the UN’s de-mining efforts. For the next three hours, as UN staff in Geneva and New York awaited word of their friends and colleagues, Arraf and her CNN colleague Wolf Blitzer became the relayers of bad news.

In her first commentary, at 9:01 a.m. New York time (5:01 p.m. Baghdad time), Arraf described the Canal’s shattered facade and the Black Hawk medical helicopters circling the building. She explained, inaccurately, that the UN had “beefed up security considerably, particularly in anticipation that someone might try to set off a car bomb.” But “still it was a UN building, and they really did not want to send the message that it was either an armed camp or part of the U.S. military.”

Arraf did not speculate on casualties, but within half an hour Duraid Isa Mohammed, a CNN translator and producer inside the U.S. cordon, spoke by telephone to CNN and reported that five helicopters had already evacuated casualties from the site. As he spoke, he said he was seeing stretchers carrying two victims from the building. The U.S. military, he observed, were “not answering any questions to the relatives of those local employees who came over to the scene by now and started asking questions about them. I see many women crying around here, trying to find their sons or husbands.”

6

With word of stretchers and distraught families, UN officials glued to their televisions around the world knew that this was no small attack. At around 9:30 a.m. New York time, CNN reported for the first time that Vieira de Mello had been “badly hurt.”

7

6

With word of stretchers and distraught families, UN officials glued to their televisions around the world knew that this was no small attack. At around 9:30 a.m. New York time, CNN reported for the first time that Vieira de Mello had been “badly hurt.”

7

Jeff Davie had done what those who worked closest to Vieira de Mello had done: gone looking for his boss.When the traffic on Canal Road stalled, he had leaped out of the vehicle, ran to the building, and sprinted up the stairs to the third floor. He found Stokes and Buddy Tillett, a supply officer, inspecting the offices to see who had been wounded. In one third-floor office Davie found Henrik Kolstrup, a fifty-two-year-old Dane who was in charge of the UN Development Program in Iraq. Kolstrup was alive but covered in glass wounds. As he writhed in pain on the floor, he was cutting himself further on the broken glass. Davie hastily wrapped Kolstrup’s wounded upper body. Stokes and Tillett arrived with a stretcher and carried Kolstrup down the stairs to the wounded area. Davie continued on toward Vieira de Mello’s office. Kolstrup was contorting so badly that he almost fell off the stretcher and down the gap in the stairwell.

8

8

When Davie made his way to Vieira de Mello’s office, he looked down through a collapsed part of the office wall and spotted below the same person Larriera, Pichon, and Salamé had seen lying faceup in the rubble and covered in dust. The man, who Davie did not think was his boss, appeared to be lying on a portion of Vieira de Mello’s office floor, which had now become the ground floor. Davie noted that while the damage caused by the attack was colossal, many of the floors and ceilings, including the flat roof of the building, had at least fallen in large slabs, pancake style, creating voids. A narrow tunnel, no wider than three feet in diameter at the top and at least thirty feet deep, separated Davie from the man below. Davie assumed Vieira de Mello was lying in the heap somewhere near this man, and he hurried down the stairs to try to find another point of entry.

Normally, in order to reach the rear of the Canal Hotel, Davie would have needed to exit through the front entrance and walk the entire width and depth of the building. But this time, at the base of the Canal Hotel staircase, he tried to turn right into those offices that had stood beneath Vieira de Mello’s. He was able to enter a cavity the size of a small room. But as he tried to move through the room, he was stopped by what appeared to be the roof of the first floor. He exited the cavity, which was pitch dark, and found a better path through the rubble of two partially intact offices.The walls and windows of these offices had been so thoroughly vaporized by the attack that he was able to walk through them to the outside rear of the building, where the truck had detonated. He was staggered by the destruction before him.

After leaving Rishmawi, Larriera had headed back upstairs to the third floor, but she felt helpless. She had watched UN staffers Stokes and Tillett open up a supply closet and remove what appeared to be the building’s only two stretchers. She went back down the stairs and caught up with Rishmawi again at the entrance to the Canal. “Have you seen him?!” she asked desperately. An Iraqi security guard approached them and said that he had seen the UN head of mission walking out of the building. Even though Larriera had left Vieira de Mello’s office ten minutes before the blast and spoken with him just two minutes before it, and though it would not have been like him to walk away from such mayhem, the Iraqi sounded so authoritative that she clung to the hope, imagining that perhaps he had taken charge of the rescue from outside the building. An American soldier trying to clear the scene approached Larriera with authority. "Ma’am,” he told her mechanically, “you’ve got to take care of yourself.We’ll take care of the rescue.”

Standing at the building entrance, she spotted a bulldozer moving across the parking lot, past the burned-out armored car that she and Vieira de Mello had driven to work in that morning, and toward the back of the building. She ran toward the bulldozer. As she did so, she spotted Stokes, who had carried Kolstrup downstairs and was standing at the entrance to the building. “Where is Sergio?” she cried out to him as she ran. “He is alive,” he shouted back. “He has been found.” “But where is he?” she yelled. Stokes pointed to the enormous pile of rubble at the corner of the building. “Over there,” Stokes said. “He is trapped in the rubble.”

Andre Valentine, the New York firefighter and EMT, had been one of the first U.S. medics to arrive at the scene, reaching the Canal around fifteen minutes after he heard the explosion. U.S. soldiers were already beginning to establish a security perimeter, but Valentine recalls, “We didn’t know who was involved or if the bad guys were still inside.” Accustomed to responding to emergencies in the United States, where a command post is established rapidly, Valentine was frustrated by the chaos. A few cool-headed U.S. personnel and UN officials had set up a treatment triage area in a grassy patch at the Canal entrance, but most UN staffers were milling about unhelpfully. “Don’t worry about calling the United Nations in New York City to tell them you got blown up,”Valentine said, infuriated by UN officials on their cell phones who were getting in his way. “It’s pretty obvious by now. Put the damn phone in your pocket. Stop smoking. I could use your help.” He grew so enraged that he instructed the U.S. soldiers around him to forbid anybody who wasn’t a medic from entering the three-hundred-foot perimeter treatment area. “I want you to shoot to kill anybody other than a four-star general who comes through here,” said Valentine. The other medics looked at him, unsure if he was serious.

Lyn Manuel had not moved. She lay propped up outside the building entrance, as dozens of her hysterical colleagues streamed past her. She tried to get the attention of someone with a cell phone so she could call her husband in Queens, New York. That year her brother had been killed in a hunting accident, and her father had died of a heart attack, and Manuel worried that her mother’s aging heart would not withstand the news of an attack on UN headquarters. But no matter how hard she tried, Manuel was unable to get the attention of those around her. People who looked at her quickly turned their heads away. “I am not good,” she cried out to Shawbo Taher, the Iraqi Kurd who was Salamé’s assistant. “I am not good,” she repeated. Taher tried to reassure her: “No, Lyn, you are good. Nothing is wrong with you. It’s just small injuries.” But as Taher recalls, “Her face was a piece of meat, a piece of bloody red meat.” The Americans were ordering anybody who could move of their own accord to evacuate the area. There was still a chance that the building would collapse. Manuel, who was still losing blood, began to lose consciousness. As she did, she took note of the scene around her. She was surrounded by bodies, beige and lifeless.

Lieutenant Colonel John Curran, who oversaw the medical evacuation, did a remarkable job. He had put his men through elaborate planning drills, rehearsing an evacuation from the Canal and scoping the neighborhood for locations where helicopters could land in the event of an emergency. Thanks to his foresight and the performance of his regiment support squadron, the injured (including Manuel) were rushed from the staging area to trucks and helicopters, then flown to U.S. medical facilities. Although many would die that day, nobody would die because of the tardiness of evacuation.

Ralf Embro, an EMT colleague of Valentine’s in the 812th Military Police unit, helped manage the shuttling of bodies between the treatment area and the helicopter landing area. Embro helped load the injured onto military trucks and helicopters. Over the next three hours, the trucks and helicopters shuttled some 150 wounded to more than a dozen U.S. military and Iraqi hospitals around the Baghdad area, then onward to more sophisticated facilities in Amman and Kuwait City.

Jeff Davie, Ghassam Salamé, and Gaby Pichon had each taken a different route to the rear of the building, where the bomber had struck. They had each stood up on the third floor and stared into the pit of human and material debris and concluded that, if their boss was alive, he would have to be reached from below and not from above.

Davie began prying at the rubble from the spot in the rear of the

Canal that he thought approximated where Vieira de Mello would have been holding his meeting. Almost as soon as he pulled some of the lighter concrete away and created a slight gap, he heard a voice that sounded like the one he was looking for. Davie squeezed up to his waist between what appeared to be a slab of the roof and a slab of the third floor, and he shouted out to the person who had made noise. Miraculously, Vieira de Mello answered, this time clearly. "Jeff, my legs,” he said. More than half an hour had elapsed since Davie arrived at the hotel.

Canal that he thought approximated where Vieira de Mello would have been holding his meeting. Almost as soon as he pulled some of the lighter concrete away and created a slight gap, he heard a voice that sounded like the one he was looking for. Davie squeezed up to his waist between what appeared to be a slab of the roof and a slab of the third floor, and he shouted out to the person who had made noise. Miraculously, Vieira de Mello answered, this time clearly. "Jeff, my legs,” he said. More than half an hour had elapsed since Davie arrived at the hotel.

Vieira de Mello, whom Davie couldn’t see but could now hear, was conscious and lucid. But while he knew his legs had been injured, he could not describe his physical predicament. Pinned beneath the rubble, he could neither see nor feel his legs. After a minute or two Davie removed himself from the gap and shouted out to Pichon, who was digging through the rubble some thirty feet away. "Sergio is alive!” Davie said. “But he’s trapped between the floors.”

Davie climbed on the rubble and spotted a twenty-inch gap between two slabs of concrete. From here, he saw the same man who had waved at him when he had been up on the third floor. Davie reached through the debris to hold his hand and spoke with him through the gap. The man said he had lost at least part of one of his legs. He said his name was Gil. It was Gil Loescher, the refugee expert who had flown in from Amman that morning. Davie told Loescher that he would go and find help.

As he raced around the Canal Hotel, Davie grabbed the first U.S. soldier he could find. It was William von Zehle, the Connecticut fireman, who was helping Valentine, Embro, and the others with medical triage in the staging area. “We’ve got people trapped,” Davie said. He escorted von Zehle around the building to the mound of rubble where Loescher was buried. Davie told the soldier that the only way to reach Loescher was likely from the shaft on the third floor. He did not think the same was true of Vieira de Mello, who sounded far enough away—at least ten feet—to require his own separate rescue effort. After taking Loescher’s pulse, von Zehle quickly left the rubble pile and made his way from the rear to the front entrance of the building, where he hoped to reach Loescher.

Other books

El fantasma de Harlot by Norman Mailer

Manifiesto del Partido Comunista by Karl Marx y Friedrich Engels

The Tycoon's Temporary Bride: Book Four by Ana E Ross

Appassionata by Jilly Cooper

White Apples by Jonathan Carroll

The Belt of Gold by Cecelia Holland

The Breaking Point by Daphne Du Maurier

Seeing Red by Crandall, Susan

Chance Harbor by Holly Robinson

The Queue by Basma Abdel Aziz