Chicken Soup for the Soul Celebrates Sisters (3 page)

Read Chicken Soup for the Soul Celebrates Sisters Online

Authors: Jack Canfield

“Right,” she said.

“Will I ever have a sister?” she asked as we drove out of the parking lot.

“No,” I said again, watching her in the rearview mirror. “I'm sorry you won't.”

“I'm like you,” she reasoned. “You never had a sister either, huh, Mommy?”

“No honey, I didn't,” I said, feeling a little bad for both of us.

“Well,” she said, with the optimistic wisdom of a five-year-old, “if I ever would have had a sister I would have really loved her.”

As I watched her drift off to sleep, I thought,

I would have, too.

Christine Pisera Naman

I

t was more than forty years ago that my big sister Marcella and I had the conversation about eyebrows. I was a little girl and she was a blossoming young woman. She was sitting at her vanity preparing to go out when she looked over at me, laughed and said, “You're the girl with no eyebrows!”

“I am not!” I retorted. But I knew she was right. My eyebrows were just stuck there above my eyes, sparse and straight, with no arch.

I often sat next to her vanity like that with my chin cupped in my hands, watching her “going out” ritual. First came eye shadow, then eyeliner on those marvelous mossy-green eyes. Pretty containers with swirled names like Maybelline and Cover Girl opened and closed with clicks and twists. Sometimes she would reach over and dab Chanel No. 5, Seven Winds or White Shoulders perfume on my neck. This anointing was like a promise that one day I would be a young woman, too.

The finishing touch to her face was always the same. She picked up a tiny brush and shaped her perfectly arched eyebrows. They were the most beautiful eyebrows I had ever seen.

Sliding into the seat in front of her vanity mirror after she had gone, I looked at my plain face. There were those cursed straight eyebrows. I was missing eyelashes that were stuck on the eyelash curler. I wore an ugly hand-me-down knit shirt that belonged to my brother and my pigtails were a mess. I would never be pretty like her even though her perfume promised something more.

On Saturdays she occasionally passed the time with me sitting on the sofa going through the pages of ladies dresses in the Sears catalog. Her long graceful finger with pearl nail-polish pointed out the dresses she liked. When I picked my favorite, it had polka dots or rufflesâor better yet, both. Her raised eyebrow and a non-committal “hmmm” started me looking beyond the flash and frills of things in life.

In a family of short, round people it was odd she was statuesqueâ nearly six feet tall. She purchased clothes at exclusive stores. I remember a sharkskin skirt, a rust-colored camel hair coat, a sable stole she saved up for and glass-heeled shoes covered with black lace.

Marcella introduced me to classical music and showed me how to twirl spaghetti on a spoon like a lady. When I turned thirteen, she took Mother's sewing scissors and cut my long braided hair. I looked so different, and perfume didn't seem too farfetched anymore.

I grew up, married and moved away from my family. As the years passed, Marcella's stunning dark hair turned into stunning silver and she never lost her sense of style. There was always a special feeling between the two of us that our distance from each other never changed.

Marcella got cancer in her early fifties. Her treatment was so successful that the family went back into normal life soon after. Twelve years later the news came that her cancer had returned. She went shopping for new clothes saying, “I'm going to go in style when I go to the doctor's appointments.”

The chemo took her hair and eyebrows and she became emaciated. I thought about the vanity mirror, the makeup, the perfume and my beautiful green-eyed sister. The next day I bought pale pink tissue paper. In it I wrapped pink nailpolish the shade of seashells, lacy pink underwear, glossy pink lipstick and cosmetics in pretty containers. The last thing I wrapped was eyebrow powder and a tiny brush. Like the dab of perfume she put on my neck all those years ago, the little pink packages were my promise to carry for her the hope of things she couldn't yet see.

We vacationed at the ocean a few weeks later and returned the next year and then the next. We sat on the porch steps eating mounds of ice cream, collected seashells everyday and watched shooting stars at night. That's how I want to remember her.

Marcella fought cancer for two more years. Three weeks before she died, she ordered new clothes from a catalog. I know I'll smile about that some day. We dressed her in the 24-karat gold stockings she loved, a symbolic gesture recognizing her courageous struggle to meet cancer head on and give it her all.

Linda L. S. Knouse

G

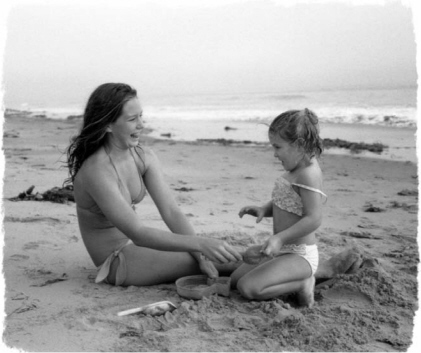

randma lived only a few blocks from the Daytona Boardwalk, close enough to smell the salt in the air and feel the ocean breezes rustle the palms in our yard as if waving to us. My sister Josie and I spent long summers there. We took off for a day at the beach every chance we could. Josie let the screen door whap shut as we headed down the steps in our sun-faded bathing suits. No shoes. No towels.

Oo, oo, ooh

ing and

ah, ah, ahh

ing all the way past the stucco and oyster-shell houses in the alley. I can close my eyes and see myself at the age of three trotting to keep up with Josie over the blistering pavement as we passed stores that sold cheesy, airbrushed T-shirts displaying Daytona and drippy sunsets. My sister was twelve and I thought she knew everything.

Josie squeezed my sweaty palm and took in a deep breath before stepping down onto the busy intersection. Glancing from side to side, she inched us along the highway, weaving between bumpers and tourists honking their horns. After making it to the shaded sidewalk and concrete barrier wall, we released our pent-up breath; her grip loosened and the feeling slowly came back into my tingling fingers. The powdered sand stuck to our scorched feet offering no relief. We hopped to the first tidal pool and wiggled our toes in the tepid, shallow water.

Josie took me up the stairs and onto the boardwalk where retired couples in straw hats and with zinc-white noses strolled, stopping to take turns posing for a picture by the famous pier. We waved to the carnival workers busy helping the children and parents in and out of cable cars. I pulled back on Josie's hand to make her stop so that I could look up at the cars lifting over our heads, watching the kids' dangling flip-flops moving out to sea. We stopped to say hello to our worn-out friend, Pappy, a stooped-over leathery man with shaky hands and a stubbled chin. He wore a dingy apron into which the tourist children dropped quarters to ride Pedro, his faithful donkey and moneymaking partner. I never got to ride Pedro. We did not have quarters to bring to the beach. But we patted Pedro's cushioned nose and Josie lifted me to stroke his stiff, fuzzy ears.

I wandered down to the edge and dug my toes into the slick sand, plopping down in front of the little waves that lapped and foamed around my bottom. Josie would grab my hand, swinging me up on her hip with a “Whee!” I clung to her like a spider monkey, my arms and legs wrapped tight.

“Loosen up, you're choking me.” She pried my arms loose.

“I'm scared. Don't go so deep.” I buried my face in her neck and squeezed.

“Don't be such a baby. I've got you good and tight. Get ready. . . . Jump!”

We leaped up and let the wave slap our stomachs and chests. Josie wrapped her arms around my waist and twirled in the ocean making giant circles. I laughed and giggled, all dizzy, as the waters swirled and pressed around us in a kaleidoscope of land and sea. We played and played, each wave swelling higher and higher, making it harder for Josie to keep her balance. We tumbled in the whoosh of the surf. The angry waves bulged and buckled, knocking us back with its mighty force. The undertow dragged us out to sea, prying me from my sister's arms. Her grip slipped.

Josie scrambled for me, arms flailing, nails clawing to keep a hold. I sunk, ears filling with water, muffling our fighting sounds. I opened my mouth to scream, water rushed in and down my throat, seemingly anxious to fill hollow spaces. I searched, head turning from side to side in the blurry water. Where was my Josie? Looking up, the shimmering distorted light called to me in the unreachable distance. I thrashed and fought but sunk further down, hit bottom with a thud, hip and thigh scraping grit and shell. I pushed at the water, as if it were a sheet on grandma's laundry line, hoping her smiling face would appear. Something solid brushed against my wrist. I felt fingers grasping then slipping in the salt water. Then she was gone. My throat burned, and the waters swirled black as I sunk further from the light.

Fingers tugged at my hair, touched my face, my jaw and moved to my bathing suit strap, hooked it and yanked me up, grabbing my tangled hair along, lifting me through the surging waters. My head broke free into the air and light. I sputtered and coughed, gagged and sneezed. Josie pounded my back, her shrieks filled my ears. A blur of people rushed toward us, concerned faces, offering arms. Josie shook her head no, and held me tighter. She rushed to shore, my body jolted against hers in the run. As the sea splashed and swished about her legs, her feet plodded onto wet sand. She dropped to her knees. I clutched tighter, refusing to let go.

I cried and gulped air until burps and belches bubbled in release. Josie rocked and shushed me. Josie tucked me in her arms and legs, closer and closer. I held on, hooking my legs around her stomach, my arms around her chest, goose-bumped and shivering in the warm, late afternoon sun. I heard Josie whisper, “Don't tell Grandma, all right? She would worry about us and not let me bring you to the beach againâyou wanna be able to come to the beach with me, don't you?”