Chinaberry Sidewalks (20 page)

Read Chinaberry Sidewalks Online

Authors: Rodney Crowell

By now I’d forgotten how to breathe.

“I liked seeing you up on stage,” she said, sounding sincere. “You’re a good singer.” She allowed that because I was in the eighth grade and she the ninth, we could never “go out”—using her fingers, she placed quotation marks around the phrase—but since we were both artists, it would be all right if, once in a while, I walked her to class. And if I ever wanted to

talk

—God, did I ever—I should give her a call. The A-bomb thus dropped, she slipped back into the party’s mainstream without disclosing her phone number, leaving me too dumbstruck to call out for it.

The opportunity to walk Rhonda Sisler to class presented itself only once. In the time it took to navigate the hallway from Mrs. Witt’s science class to Mr. Cassius’s art class—about fifty yards—she shared in detail her dream of moving to France and becoming a well-known artist. This was a vision of the future so far beyond me that, feeling the need to match her farsightedness with some forethought of my own, I spat out the first unexamined thought that sprang to mind. “Oh, that’s all right,” I blurted. “You can stay right here and do that.”

I knew immediately that this was irrevocably stupid, but before I could dream up a do-over she nailed me: “Of all the boys in this school, I thought you’d understand me,” she said

very

seriously.

I tried retracing my steps, but the path was closed. She had moved to Paris without me.

And so I came to understand—too late—that golden girls were as susceptible to isolation as tongue-tied boys with learning disorders. When every other pretty girl cared only about potential football stars, why Rhonda had her sights set on art and music and dual citizenship was, given the time and the place, almost incomprehensible. In fact, against a backdrop of oil refineries, chemical plants, paper mills, salvage yards, and beer joints, how she knew such things even existed was a bigger mystery to me then than tetrahedral triangles are now. Yet as I kept slogging through adolescence, I came to revere this force of nature as a symbol of possibility. Though years away from knowing who I was, thanks to her I finally knew what I wanted. I wanted out.

One rainy Saturday afternoon in March, I hesitated before answering a knock on the door. Since recent visitors over, say, the last fifty-two months numbered in the single digits, greeting callers had become a forgotten propriety around our sodden little abode. Company was a rare thing indeed, and I took a minute to rifle through my store of worst-case scenarios before calling out, “Who is it?”

On the porch were Jerry and Jeanette Hosch, both of whom I’d known since our mothers had hired on as janitors at Jacinto City Elementary School. Although they’d moved away the summer before seventh grade and I hadn’t thought of them since, I knew a leaking roof wouldn’t faze them in the least and invited them in without hesitation.

Jerry came straight to the point. The rock-and-roll band they were putting together in a little rice-farm township some thirty miles northeast of Jacinto City needed a guitar player and singer. Even out there in the sticks, paying jobs were plentiful enough for every band member to make, three weekends out of four, ten or twelve bucks. He and his sister had agreed that I was about as close to a Beatle as they could hope to get and sure would appreciate it if I’d think about joining up.

When I announced that I was leaving home to start a band, my father was working on the engine of his latest used-car disaster, a baby-blue and white ’57 Ford whose previous owner had most likely relied almost exclusively on public transportation. Dragging his upper body from beneath the hood, he made a quick study of the middle distance a foot above my head and said, “Tell ’em you write your own songs, son.” Nodding his satisfaction with the pith of this advice, he peered back into the mouth of this $175 lemon, then issued a barrage of expletives that I took as a sign of approval.

My mother’s response was no less typical. “Go ahead, son,” she said, pointing to some numinous elsewhere beyond our screen door. “There ain’t a day goes by that I don’t wish I’d’ve told Mama to let the Devil take the hindmost and gone on to that school. If this shit round here don’t kill us when it falls down, me and him might catch up with you out yonder.”

To find Crosby, Texas, one had to travel east on Interstate 10 and turn north on Farm to Market Road 2100 and then, heading away from the Lynchburg Ferry and the San Jacinto Battlegrounds, pass through the townships of Highlands—so named for its location on the banks above the river—and Barrett Station, an ex-slave settlement dating back to the Emancipation Proclamation, before reaching the Highway 90 intersection and the outskirts of your destination. Beyond the fairgrounds, rodeo arena, and antiquated water tower lay the town center, where Glover’s Burgerland, Hechler’s Department Store, the post office, Stasney’s Feed Store, Swanson’s Drug & Appliances, Prescott’s Esso, and Jay’s Grocery huddled alongside the Southern Pacific Railroad tracks as living proof that wars, tornadoes, and economic depression couldn’t break the will of this turn-of-the-century whistle-stop.

North of the tracks, another ten-mile stretch of road cut across the irrigation ditches, rice fields, and cattle farms lining Lake Houston’s eastern shores. Clarence and Flora Mae Hosch maintained a two-acre outpost half a mile from the Farm to Market Roads 1960 and 2100 junction, and I arrived there on a Friday less than a week after the surprise invitation to join the band. On Monday morning I enrolled in the tenth grade at Crosby High School.

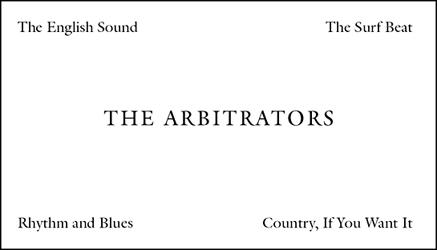

After the murk and misery of junior high, to be fifteen going on sixteen and a big-shot member of the Arbitrators—a name we’d plucked from the

A

’s in the dictionary—and hauling down a little spending money and answering to nobody was a mighty potent cocktail.

Jerry owned a ’63 Chevy, in which the band, guitars, amplifiers, and drum kit fit snugly. Crammed in that car like sardines, Ronnie Joe Falk, Jeanette, Jerry, Ronnie Hechler (the band manager), and yours truly traveled to small towns like Huffman, Humble, Barbers Hill, Dayton, Highlands, and Baytown for paying engagements. Hechler even had cards printed up:

I soon adopted the habit of skipping school in favor of sleeping late and spending idle afternoons drinking beer and smoking cigarettes with Jerry and Bernie Wilson, high school dropouts and my new role models. When the principal called me into his office to discuss my eight absences in the first month, I made up a big lie about there being no such thing as an unexcused absence at Galena Park High School, to which perjury I tacked on the assurance that one phone call would validate my claim. He ignored this bluff and forthwith delivered a three-pronged sermon on the perils of negative influences, Jerry Hosch’s well-known disdain for authority, and the importance of getting off on the right foot. When he’d finished reading aloud the state laws pertaining to truancy, I was given a mimeographed copy of the student handbook and abruptly dismissed. Final score: Mr. Prohazcka, fifty-six; cocky new rock-and-roll star, zero.

During the years that our mothers scrubbed floors, Jeanette and I had been trusted after school to walk the two blocks to her house where, under the not-so-watchful eye of her older sister, we were left to do pretty much as we pleased—climbing fences, throwing rocks, shooting marbles, making mayonnaise sandwiches, watching

Adventures of Superman

, and snooping around for her big brother’s dirty magazines. Come four-fifteen, my mother would call from the sidewalk that it was time to go, and we’d walk the five blocks home.

Out of the blue, Robbie Green started spewing nonsense about this after-school arrangement. A well-known mama’s boy, Robbie was a full head taller than his peers, his protruding lower lip quivered when he spoke, and his father was rumored to have skipped town with his wife’s inheritance. And among the more gossipy women, Mrs. Green herself, being tall and beautiful and without a man, was suspected of being up to no good. I’d been inside their house twice and the nattering about her didn’t wash. True, it was a strange household, but whose wasn’t? If Robbie and I had gotten on better, I’d have hung around his place on a regular basis, since they had an air conditioner in the living room window. But according to Robbie, what Jeanette and I were up to was “too weird,” and he threatened to “set the record straight.” Why being looked after by her sister was at all weird and what record needed straightening was never elaborated on. And then, on the third day, he declared I could “no longer run from the truth” and began babbling about unwanted children and Jeanette saving herself for her wedding night and me being long gone once I’d gotten what I wanted—the kind of spiel that is usually delivered by some uptight grown-up.

By the fourth day, Jeanette had had enough. “If you don’t quit mouthin’ off at us,” she warned him, “I’m gonna teach you a lesson.”

Instead of heeding her tone, Robbie made some deprecating remark about her mother’s hairstyle that wasn’t, as I recall, too far off the mark; Flora Mae wore a cult-religion bouffant piled so high on her head that even my mother made jokes about it looking like a two-story bird’s nest.

Jeanette responded by throwing a solid punch that opened a gash in Robbie’s lower lip, and for a long moment he stood there examining the blood on the tips of his fingers and making sure it was his by tasting a drop or two.

Then, despite being two feet shorter, Jeanette wrestled the poor fool to the ground and made good on her promise as a crowd of students cheered her on. Over and over again, Robbie yelled for somebody to get her off him, loud enough to be heard back in his mother’s house, but no one volunteered.

“Me and J.W. figured we might as well move on out here to be close to the boy,” my mother told Flora Mae. I was hiding behind Jerry’s bedroom door and sneaking looks out the window at my father, who sat behind the wheel of a four-year-old Ford pickup. “We got no intentions of ruinin’ what he’s got goin’ on with his band and all,” she continued. “We just wanted to let y’all know we’re here—in case he wants to come back home.”

In the nine months since I’d seen my parents, something in me had changed. I no longer cared if they killed each other, or if the house they’d rented across the street from Ronnie Joe Falk’s was a step down from the one they’d just had repossessed. It was an eighty-year-old farmhouse whose land had turned into Crosby’s only neighborhood, and an indoor toilet and a back bedroom had been added on sometime later. Whereas the original foundation was stacked quarry rock, the addition rested on a thin slab of concrete and was caulked to the exterior wall, and to access the main part of the house one had to climb the rickety back steps and pass through a kitchen the size of a broom closet. Due to these renovations the back door had been repositioned near the far end of a windowless wall facing the driveway, so the freedom I had cherished living with the Hosch family continued unabated. In fact, the yearlong crime spree Ronnie Joe and I went on resulted directly from the placement of that door.

A typical evening’s burglary started with the two of us pushing one of our parents’ cars halfway down the block before cranking it up for a late-night joyride. If breaking and entering was our fantasy, stealing tools out of some old farmer’s barn was our reality. We did manage to pry into the high school gym and steal all the varsity football team’s game jerseys. Matching player and number, we spent the rest of the night flinging each jersey into the corresponding yard, including Ronnie Joe’s, and got up early the next morning to drive around admiring our handiwork.

Our most spectacular act of delinquency came on the night Ronnie Joe climbed the water tower. Belonging to the class of ’65, he intended to burn the canvas “Seniors ’64” banner that some daredevil had hung from the metal walkway circling the tank. He climbed the tower’s exposed ladder, tied eighty feet of gasoline-soaked rags to the sign, and climbed back down. I then lit the dangling fuse with a kitchen match, and the two of us watched the blue-edged flame traveling upward as fast as the adrenaline charging through our bloodstreams. A whoosh and a ball of flames pronounced our mission complete, and from the Falks’ back porch, three blocks away, we lingered for a few minutes in its waning glow before heading off to bed.

The next day, a handful of students and Saturday shoppers were milling around the tower’s base, where kitchen matches were strewn over the ground like leftover party favors. Such was the attitude toward criminal investigation around Crosby that I overheard the sheriff say, “There ain’t no need in worryin’ about who done this, since they ain’t nothin’ else up yonder to burn down.”

Only once did Ronnie Joe and I get into real trouble. Out on the far south side of Houston, he’d tried to make a U-turn and gotten his mother’s Ford stuck in a ditch. The road was desolate, as most in that neck of the woods were, and the prospect of a long walk hung over our heads like a burned-out lightbulb. Flagging down the first set of headlights was an equally daunting proposition, for most of the people traveling there at that hour were lost, stupid, or dangerous. Or, like my partner and me, all three.