Chinaberry Sidewalks (24 page)

Read Chinaberry Sidewalks Online

Authors: Rodney Crowell

“Listen up over there,” he said, for once dropping the subject of Rafe Blanton. “I don’t give a good goddamn how you wound up in here. Personally, I think you’re a limp-dick pussy who I’d rather wipe my ass on than take a look at. But what I need to know is the number of that doctor who wrote you that script for fucking reds.”

My parents were drained of their color for months. My mother lost twenty pounds she didn’t have to spare, and my father went through cartons of Pall Malls like gumdrops. I could practically hear eggshells crunching whenever they walked into a room with me in it. The funny thing is, I felt calm inside, even oddly restored. Overdosing on barbiturates caused a shift in my perception. The pain of losing Annie was no less prevalent, but I knew it would pass. And, that it probably wouldn’t be anytime soon, no longer seemed impossible to bear.

P

ART

F

IVE

Transition

I

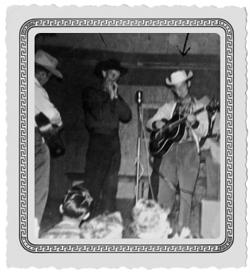

sometimes wonder how my father might’ve reacted had he known—on the day we saw Johnny Cash, Jerry Lee Lewis, and Carl Perkins at the Magnolia Gardens Bandstand—that twenty-three years later I’d produce a live recording of those same three artists. Doubtless the man I idolized would’ve seized the microphone and gloated to the audience that his son was some kind of wunderkind they’d damn well better watch out for in the future. Then again, since it was only through songs that he was ever truly comfortable expressing the dark places in his heart, there’s no reason to think he wouldn’t have taken it as just another sign that even back then—he was almost thirty-five the day we heard them play—such glories had already passed him by. For that reason I often wish I’d told him how, in the early seventies, when I first found myself sitting in on late-night Nashville song-swapping sessions with, among others, Guy Clark, Townes Van Zandt, and Mickey Newbury, I hung on to my seat in the circle only by trotting out the old folk ballads I’d heard him sing as far back as I could remember. Thanks to my father, I knew all the words to “The Great Speckled Bird,” “May I Sleep in Your Barn Tonight, Mister?,” “Put My Little Shoes Away,” and “The Rosewood Casket” and could sing them pretty convincingly, which musical currency purchased me enough time in the presence of these master songwriters to absorb something of their craft. Luckily, I was a fairly quick study and in a year or two turned out a handful of songs that Emmylou Harris was interested in recording, and at her invitation I moved out to Southern California and joined the band she was putting together.

While working with Emmylou, I met Rosanne Cash, who thought it would be a good idea if I were to produce her debut album for Columbia Records. The pairing clicked personally as well as professionally, and before long we were married. I brought to the relationship a twenty-two-month-old daughter, Hannah, whose custody I’d been granted in an amicable divorce nine months before. A little over a year after the birth of our first child, Caitlin, Rosanne was again pregnant—this time with Chelsea—and her misgivings about raising children in Los Angeles led to our packing up and moving back to Nashville, where she had family and I had good friends. The youngest of our brood, Carrie, was born seven years later.

As the seventies were closing down, I was beginning to suspect my nearly decade-long need to put as much distance as possible between me and the past had outlived its usefulness, and that the five years I’d spent avoiding my parents, and Gum Gully, like the plague had more to do with finding comfort inside my own skin than escaping our family history. The cause of this slow dawning was my own fatherhood, and for the first time in my life I started shifting my focus away from what had gone on before and onto what was coming to pass. My reward? To witness a growing bond between my children and their grandparents that put me in mind of the ties I once shared with Spit-Shine Charlie and Grandma Katie. And also to finally realize that life’s basic impulse—given half a chance, even in death—is to heal itself. By the late eighties, my attitude toward old wounds and subsequent anger had changed entirely for the better.

But to return briefly to Magnolia Gardens and to my speculations about my father’s likely response to the career I ended up having, I can honestly say that not until long after I’d had a gold record and made numerous appearances at the Grand Ole Opry did it ever occur to me that my professional life was in fact the one he’d always dreamed of for himself. The two of us never spoke of such things, for that would’ve meant acknowledging his disappointments. No, I was only too happy to hold up my end of an agreed-upon forgetfulness that allowed him to feel proud of me without speaking a word of it in my presence. I always knew, of course, that he was back in Texas singing my praises to anybody who’d listen, and even more loudly to those who couldn’t have cared less.

Late in September of 1979, my father and I went to the Houston Astrodome to watch his beloved Astros play baseball. Through a friend in the music business, I’d landed a pair of dream tickets—seventh row behind home plate—and flown in to celebrate the team’s first winning season in almost a decade. The last such father-son outing that either of us could remember, save for our foray into house building, was an Oilers game in 1963. In the nine years since I’d left home, there were long stretches when we’d had very little contact, and I was hoping this ballgame would begin a new chapter in our lives.

As the evening progressed, I became increasingly aware that my childhood hero was in a poor state of health. Besides the astonishing number of cigarettes he was lighting, one off the other, his skin seemed stretched taut across a bloated bloodstream badly in need of a high-pressure escape valve. Dark blue capillaries lined his reddened cheeks like a city map, and his breathing alternated between a rasp and a perforated wheeze. All of this was made even worse by a dye job that rendered his wavy hair a more unnatural shade of blue-black than Nelda Glick had sported in her snuff-queen heyday.

Adopting an obsequious tone, I put forth a lenient question that I’d much rather have posed as a screaming wake-up call. “Don’t you think maybe you should cut back on the cigarettes, Dad?”

“I have,” he said, failing to register my desperate worry.

“Really? How much were you smoking before?”

“More than I do now.”

By the end of the eighth inning we’d seen enough baseball and, like the other ten thousand Astros fans trying to get a jump on the traffic, headed for the exits. Standing up to leave, I counted sixteen Pall Mall butts stamped out beneath his seat.

The next morning I made a point of informing my mother that, if something wasn’t done, her husband was headed for a heart attack, a stroke, or both, to which she replied: “He’s got a lot on his mind.”

“What does that have to do with his heart blowing a freaking gasket?” I snapped, thinking my testiness might convey a sense of urgency. “We need to get him to see a doctor as soon as possible.”

“I told him he needs to,” she fired back, “but when did J. W. Crowell ever listen to a word I say? Besides, a while back this angel come down to tell me the Lord has a plan for your daddy, and I believe it. Not long after that, he walked in and told me he wanted to turn his life over to the Lord. I like to’ve broke down and cried. You know how long I been waitin’ for him to accept Jesus? You can try to get him to go to the doctor, and I pray he listens to you, but as long as he keeps goin’ to church, I ain’t arguin’ with him.”

Thus did I learn that my father had been—as they say—saved. And though I doubted the day would ever come when he’d acknowledge a power greater than his own ego, I was sincerely happy for my mother. If anyone deserved to tame the lion, it was Cauzette. Yet I couldn’t help wondering what the hell would become of Ole J-Bo?

Saturday afternoon, I found him sitting in his favorite lawn chair, smoking. He’d been there awhile, waiting for me to come out and admire his one and only addition to the house we’d built together. This was the situation I’d been hoping for.

“Nice side porch, Dad. Looks like you get both morning

and

afternoon shade.”

“Me and an ole boy from over in Humble built it in one weekend. Cost me a hundred and twenty dollars, countin’ what I paid him. Got all the materials off a cost-plus job over at Exxon.”

“Any way I can get you to see a doctor about that shortness of breath?”

“I been studyin’ about buying a Winnebago so me and your mama could drive around some on the weekends, maybe take off in it when I retire. Nah, I don’t need to see no doctor.”

Rationalizing that it would do my parents more good than it would do me harm, I invited myself to join them on Sunday morning. Upon reaching their church, the first thing I noticed was how much Pentecostalism had changed since I’d last witnessed it. Lone-wolf sermonizers like Brother Pemberton and Brother Modest, who in their day ran the show according to their own particular interpretation of the Scriptures, had been supplanted by a his-and-her parsonage that was sorely lacking in religious theatricality. My immediate impression was that the gender-blurring seventies had completely neutered the concept of hellfire and brimstone. Within this new model, you got some pussy-whipped Adam preaching all this middle-of-the-road stuff while his disapproving Eve assumed the role of the official first lady—and if, by chance, she played the organ, so much the better.

The Assembly of God in Crosby, Texas, was home to thirty or forty regulars, all of whom, I gathered, preferred its redbrick simplicity to the more imposing Baptist or socially acceptable Methodist branches in town. The preacher, a pudgy mid-forties sort of fellow whose name I never caught, but whose guacamole-colored leisure suit and brown superwide tie I’ll never forget, stood behind the pulpit, smiling beatifically on his flock and exuding reverential certainty. Five steps to his left, looking every ounce like a begirdled Queen Bee, sat Sister So-and-So in a straight-back chair. To her left was an old Lowrey parlor organ she’d no doubt dragged from one church to another for twenty-plus years. My instant dislike for this woman had more to do with the chain I imagined she’d tied to her husband’s genitalia—fond of giving it a sudden yank whenever the question of who was boss came up for review—than her hidebound personality.

My father sat in another straight-back chair five steps to the preacher’s right where, on cue, he picked up his guitar and, to get the ball rolling, sang “The Old Rugged Cross” with way too much vibrato for my taste. In his prime he never would’ve subjected a honky-tonk to such soppiness. In this new incarnation, however, he was pouring it on like a huckster. It was as if he’d been told that, in church music, his natural instincts were a detriment. But from where I sat, the vibrato served only to turn a damn good singer into a poor man’s Don Ho.

When he finished singing, the preacher nodded his high-handed approval and excused my father to join his family in the pew. Watching the once-proud Casanova climb down from that Christian stage to cross a room filled with pious silence filled me with both sadness and anger. Surrender didn’t look good on him. Missing his cocky arrogance and hating seeing him so sanitized, I found myself wishing he’d jump up and bark, “Cauzette, this shit’s for the birds; me and the boy’s goin’ to the house.” Then I’d have the old J-Bo back.

Brother What’s-His-Name’s strong suit was detecting apathy, but he was also highly sensitive to insolence. It was his congregation’s misfortune that on this particular Sunday I’d walked through the doors brimming with both. And since I knew that any Pentecostal Bible-thumper worth his salt was loath to suffer any dissidents—especially one visiting from California whose name occasionally appeared in the newspaper—I braced myself for a showdown.

Having a smart-ass near-celebrity in the pews threw this fellow right off his game. His rhythm was knotted and his necktie too tight. The congregation sensed his discomfort, and I could feel their resentment mounting. The difference between their God and mine, I realized, was a matter of semantics, but because I held the Queen Bee mostly responsible for my father’s emasculation, I decided to play the uppity outsider and challenge their leader’s supremacy indirectly.

Brother What’s-His-Name had no ability to create a sense of impending doom among his followers, and none of Brother Pemberton’s flair for snatching a flock of lost sheep out of the Devil’s flaming inferno. But then, who did? I will concede that he preached a decent sermon, quoting the Bible in all the scripted slots and rebuking the pitfalls of contemporary life, putting in pedestrian terms the evils of television as opposed to the word of the Old Testament God. But there was no outlandish context that placed the congregation in mortal danger. Whatever was going on inside my mother’s brain that made her settle for such low-stakes salvation, I didn’t like it. In 1959, she’d have stomped out denouncing the unremarkable reverend as unfit to pass the offering plate around.

Mercifully, he ceased his oration and signaled for Sister So-and-So to tear into a version of “Just as I Am.” It’s to their credit that they made short work of getting the folks out of their seats and onto their knees. Judging by the rush to the altar, I concluded that the congregants were standing eagerly behind their pastor in a time of need. If my parents were torn between joining their friends or siding with me, neither showed it; they were among the first to bolt from the pews, while I adamantly stayed put.

Maybe twenty minutes into being the lone salvation holdout, I noticed that some of the faithful had forgotten themselves. Besides the twenty-odd dutiful penitents whose numb knees and aching backs had resulted from our clash of egos, I saw an old man wind his pocket watch in between waving his hands high over his head in holy rapture. An attractive middle-aged woman seemed to be fondling the breasts of a very attractive teenage girl, both of them apparently grateful the preacher and I were at loggerheads. Best of all was watching Sister So-and-So work up a sweat behind the organ while throwing me hard glares I interpreted as telling me to get my skinny, stuck-up California ass down to the frigging altar so the righteous among us could go home and eat some fried chicken and potato salad.

At around the thirty-minute mark Brother What’s-His-Name called it quits. I liked the guy then. He knew when he’d been beat. I give him credit for taking a run at breaking me down, but out of respect for the predecessors I’d known this just wasn’t possible.

Three months later, he and Sister So-And-So were replaced by thirtysomething hot shots—a his-and-her extension of Pentecostal Christianity’s newly acquired business savvy—and my father was summarily dismissed as the church’s regular performer. According to the cunning new first lady, they were taking their Assembly of God in a more contemporary direction. In other words, old-timey gospel music ate too far into potential profits to suit these two up-and-comers. Religion was undergoing a face-lift, and throwbacks like Brother and Sister Crowell could only impede progress. Evangelicalism was the new order of the day.