Chocolate Wars: The 150-Year Rivalry Between the World's Greatest Chocolate Makers (31 page)

Read Chocolate Wars: The 150-Year Rivalry Between the World's Greatest Chocolate Makers Online

Authors: Deborah Cadbury

Tags: #Food

BOOK: Chocolate Wars: The 150-Year Rivalry Between the World's Greatest Chocolate Makers

6.72Mb size Format: txt, pdf, ePub

George Jr.’s milk chocolate bar finally rolled off the production lines in June 1905. Oddly, it was given hardly any advertising support and was presented in plain and cheap wrapping to keep the price down. Sales were slow and George’s estimate of twenty tons a week began to look reckless. The economy of the launch was not due to Quakerly frugality but a result of the company being stretched to the limit by their prolonged struggle with the Dutch over cocoa, the core of their business. Van Houten’s alkalized cocoa had cornered 50 percent of the market in Britain. Sales of Cadbury’s Cocoa Essence, their leading brand for thirty years, continued to fall in 1905.

Without knowing Van Houten’s formula, George Jr. was once again required to come up with a solution—and fast. It wasn’t long before he brought a new taste before the board: Cadbury’s very own brand of alkalized cocoa

.

Once again the board agreed that the new cocoa had a good flavor. The sales teams, however, were baffled as to how to promote this new drink without undermining their old one. Cadbury’s name stood for pure, unadulterated food. If they promoted

the superior taste and solubility of their alkalized cocoa, they risked drawing attention to weaknesses in Cocoa Essence. Refusing to hesitate, George Jr.’s new cocoa was launched at Christmas 1906. Packaged in colorful chocolate brown tins, its new name was boldly displayed on the side in large letters: Bournville Cocoa

.

.

Once again the board agreed that the new cocoa had a good flavor. The sales teams, however, were baffled as to how to promote this new drink without undermining their old one. Cadbury’s name stood for pure, unadulterated food. If they promoted

the superior taste and solubility of their alkalized cocoa, they risked drawing attention to weaknesses in Cocoa Essence. Refusing to hesitate, George Jr.’s new cocoa was launched at Christmas 1906. Packaged in colorful chocolate brown tins, its new name was boldly displayed on the side in large letters: Bournville Cocoa

.

In the space of one short year, George Jr. had launched the two creations that he hoped would save the company from the Swiss and Dutch onslaught: Dairy Milk and Bournville Cocoa. By this he would stand or fall. By this, the company might stand or fall. Like Hershey in America, all he could do was wait.

As the Americans and the British strived to launch their own versions of Swiss milk chocolate, Swiss businessmen and bankers were already leaps ahead of them. The creator of milk chocolate, Daniel Peter, the man who had struggled with his invention for so many lonely years, found himself greatly in demand.

Since 1896, Peter had not looked back. Investment in his company, Société des Chocolats au Lait Peter, increased rapidly. In the three years since 1900, Peter’s authorized capital rose from 1 million Swiss francs to 1.5 million, and his sales reached 6 million Swiss francs. In addition to his chocolate works at Vevey, Peter developed another plant to meet the rising demand for milk chocolate thirty miles northwest in Orbe.

In January 1904, Daniel Peter was approached by another Swiss confectioner, Jean Jacques Kohler, who wanted to join forces. Although Kohler’s company was worth less than half of Peter’s, his chocolate products complemented Peter’s range, and he had strong sales teams in France and Switzerland. For sixty-eight-year-old Peter, it allowed him to step back from the front lines of the business, leaving the capable and likeable Kohler in charge. That same month the two firms merged to form Société Générale Suisse de Chocolat with authorized capital of 2.5 million Swiss francs.

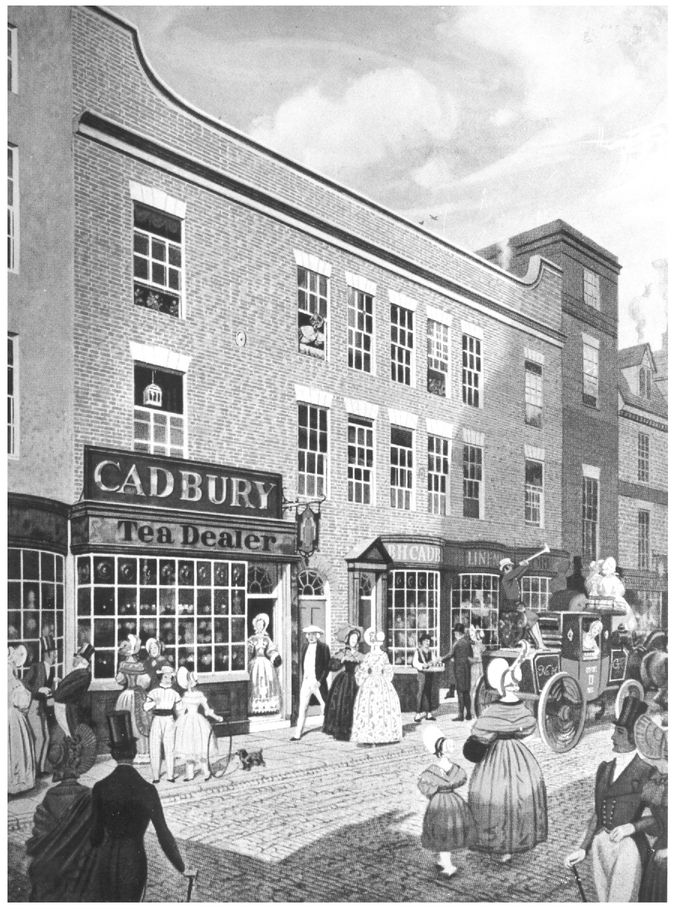

John Cadbury’s tea and cocoa shop in Bull Street, Birmingham—the start of the Cadbury chocolate business. From a drawing by E. Wallcousin, 1824.

(COURTESY OF CADBURY)

George Cadbury, age 25, taken in 1866 at a time when the family cocoa business was close to failure.

(COURTESY OF THE CADBURY FAMILY)

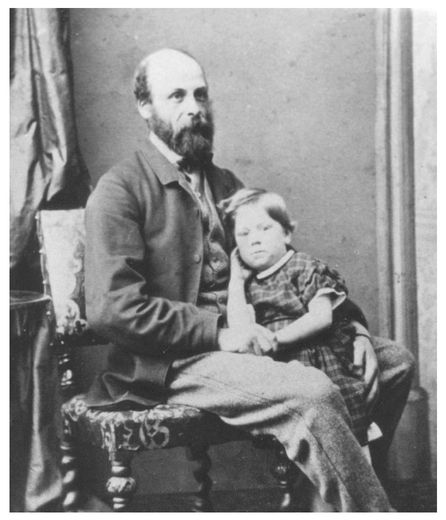

Richard Cadbury and his son, Barrow, in 1866.

(COURTESY OF THE CADBURY FAMILY)

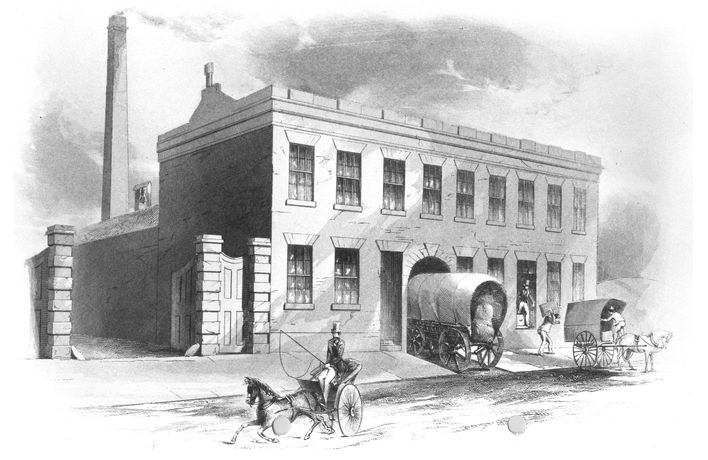

The Cadbury’s Bridge Street factory in Birmingham in the mid-nineteenth century. (COURTESY OF CADBURY)

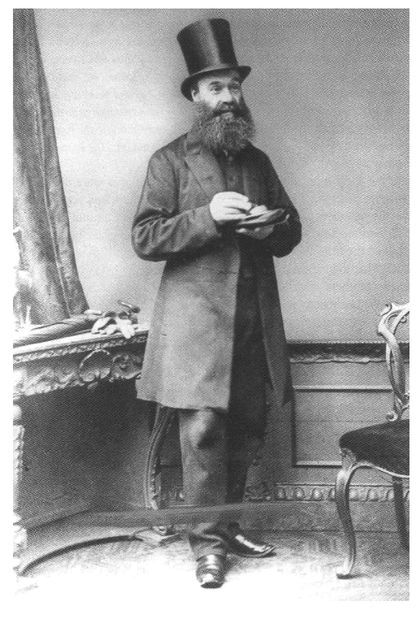

Dixon Hadaway—Cadbury’s first “traveller.”

(COURTESY OF CADBURY)

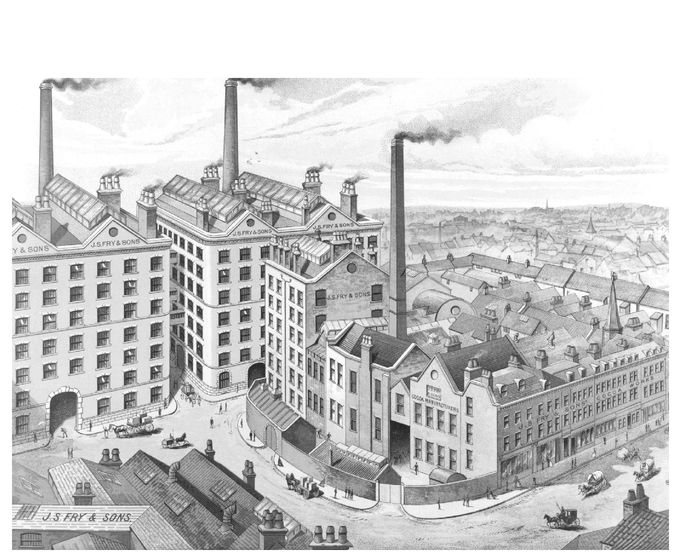

An advertisement for Fry’s cocoa. (COURTESY OF CADBURY)

The Fry family of Bristol ran the largest chocolate factory in the world in the nineteenth century. (COURTESY OF CADBURY)

The Cadbury brothers breakthrough product: a purer form of cocoa.

(COURTESY OF CADBURY)

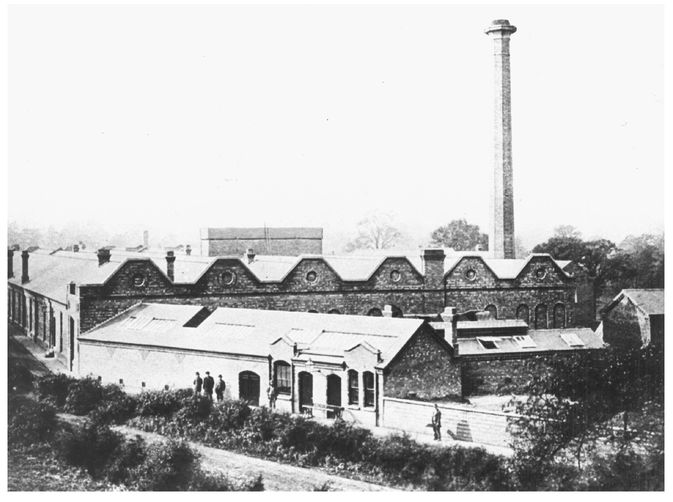

Exterior photo of Cadbury’s Bournville, 1879. This is the first known photograph of the Bournville factory. (COURTESY OF CADBURY)

Other books

Playing Hearts by W.R. Gingell

Bayou Wolf by Heather Long

Dog Crazy by Meg Donohue

Desire #1 by Carrie Cox

Zero Six Bravo by Damien Lewis

Taken by the Trillionaires by Ella Mansfield

Meta by Reynolds, Tom

The Perfect Proposal by Rhonda Nelson

A Walk in the Woods by Bill Bryson

Drawn Deeper by Brenda Rothert