Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years (172 page)

Read Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years Online

Authors: Diarmaid MacCulloch

Tags: #Church history, #Christianity, #Religion, #Christianity - History - General, #General, #Religion - Church History, #History

Changing attitudes to death and Hell mark a growth of this-worldly concerns in a large part of contemporary Christianity. That is as much exemplified in the concern for political justice in liberation theology as in the 'Prosperity Gospel' strand of Pentecostalism, even though the politics of both frequently stand in complete contrast. There are other contrasts: Pentecostals often seem preoccupied in their liturgy by the joy of their faith, while theologies of social justice are more inclined to remember that at the heart of Christian stories, after the birth of a helpless baby in an obscure province of the empire, there is a gallows built by the colonial power. A different sort of this-worldliness is to be found in the continuing fascination which Christian art, creativity and sacred places exercise over the Western mind, however secularized. In England, cathedrals and their choral music have never been better loved, cherished or maintained through public generosity. Their vigorous life, from Evensong to teashops, contrasts with the empty Sainte-Chapelle in Paris, in its emptiness a symbol of the troubled history of the modern French Church, and in its beauty a further twofold symbol. The Sainte-Chapelle speaks of the medieval conviction that the relics of the saints opened an entrance to Heaven (particularly for the king who paid for them), but with its modern turnstiles and sightseeing crowds, it also reflects the vague modern hope that beauty and antiquity might just open an entrance to Heaven. How does tourism relate to pilgrimage, and can the Church help tourists to become pilgrims?

It is one of the curiosities of Western society since the Enlightenment that much of its greatest sacred music (though by no means all) has been the work of those who have abandoned any structured Christian faith. Edward Elgar, who created English Catholicism's greatest modern sacred oratorio out of Cardinal Newman's poem

The Dream of Gerontius

, exclaimed at the time of its first performance that he had always believed that 'God was against art', and towards the end of his life, he lost whatever Christian faith he had. Michael Tippett, who explored the anguish of suffering humanity through Negro spirituals in

A Child of Our Time

, and stood alongside Augustine of Hippo and Monica in the garden at Ostia as they reached out to glimpse God in

The Vision of St Augustine

, never embraced any Christian affirmation. The agnosticism of the clergyman's son Ralph Vaughan Williams did not prevent him editing the finest hymn book in the English language,

The English Hymnal

, or creating even greater splendour around the Christian tradition of sacred verse in numerous song-settings and choral pieces; the passionate verse of the English parson-poet George Herbert is now almost inconceivable without Vaughan Williams. Even Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, so influential in the reconstruction of Russian Orthodox church music, which remains one of the main ambassadors of Orthodoxy beyond its boundaries, was an aggressive atheist.

111

What do we make of this paradox? It might be seen simply as the logical historical outcome of the phenomenon which we noted as a mark of advancing secularity in eighteenth-century Enlightenment Europe, that Christian sacred music could become detached from the liturgy into the concert hall (see pp. 788-9). But that very possibility says something about the special quality of music among the arts. The writer Andreii Beliy, one of Rimsky-Korsakov's colleagues in the late-nineteenth-century artistic impulse to forge a new unworldliness for a worldly society styled the Symbolist Movement, pointed out that 'music is not concerned with the depiction of forms in space. It is, as it were, outside space.'

112

Pseudo-Dionysius, Aquinas and a host of mystics in East and West would have said the same about God, and God himself said it about himself, in the midst of a burning bush on the Sinai peninsula. Perhaps music might be one way past the impasse which has been the experience of some versions of the Protestant Reformation, tangled in the torrent of words which has flowed around the Word which dwelt among us, full of grace and truth.

This book has no ending, because, unlike Jesus Christ, historians in the Western secular tradition stemming from the Enlightenment do not think in terms of punchlines to the human story. This history can draw attention to what has gone before: an extraordinary diversity called Christianity. A couple of lines of poetry from the great English dissenting hymn-writer Isaac Watts commonly raise a smile among choirs who sing them frequently, thanks to a shift in English usage:

Let every creature rise and bring

Peculiar honours

to our King.

113

The image of a menagerie presenting a collection of bizarre objects to the enthroned Saviour in the Last Days is not what Watts was invoking, pleasing thought though it is. Watts in his eighteenth-century English wanted to talk about the glorious particularity of individual religious experience, the appropriateness of one Christian manifestation to one situation; yet all of them fixed intently on that which is outside space. So often what in one age seems bizarre - the property of a derided or persecuted sect - becomes the respected norm or variant in other, later circumstances: the abolition of slavery, the ordination of women, the avoidance of meat-eating or tobacco.

114

Hans Urs von Balthasar reflected wisely on an aspect of the Church's history which might give some contenders in present battles pause when he stressed the ultimate individuality of spiritual experience: 'Nothing has ever borne fruit in the Church without emerging from the darkness of a long period of loneliness into the light of the community.'

115

Most of Christianity's problems at the beginning of the twenty-first century are the problems of success; in 2009 it has more than two billion adherents, almost four times its numbers in 1900, a third of the world's population, and more than half a billion more than its current nearest rival, Islam.

116

At least Christian history offers plenty of sobering messages for overconfidence. The more interesting conundrum for Christianity is a society in which polite indifference has replaced the battles of the twentieth century: Europe, which is not so much a continent as a state of mind, to be found equally in Canada, Australasia and a significant part of the United States. Can there be a new Christian message of tragedy and triumph, suffering and forgiveness to Europeans and those who think like them? Does secularism have to be an enemy of Christian faith, as Nazism and Soviet Communism were enemies, or does it offer a chance to remould Christianity, as it has been remoulded so often before? Can the many faces of Christianity find a message which will remake religion for a society which has decided to do without it?

Original sin is one of the more plausible concepts within the Western Christian package, corresponding all too accurately to everyday human experience. One great encouragement to sin is an absence of wonder. Even those who see the Christian story as just that - a series of stories - may find sanity in the experience of wonder: the ability to listen and contemplate. It would be very surprising if this religion, so youthful, yet so varied in its historical experience, had now revealed all its secrets.

Notes

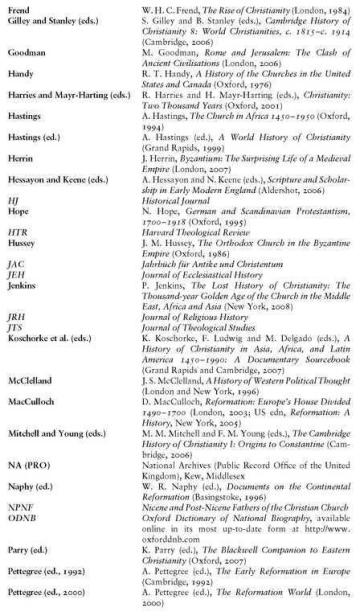

Abbreviations

Introduction

1

A superb analysis of this beautiful hymn is to be found in J. R. Watson,

The English Hymn: A Critical and Historical Study

(Oxford, 1999), 86-90. Its words are much enhanced by a later tune, 'Love Unknown', written by the British composer John Ireland (1879-1962). Crossman borrowed for his poem the metre of the 'Geneva' metrical version of Psalm 148 commonly sung in England in his time, 'Give laud unto the Lord', and mightily improved on the psalm version; perhaps he was trying to show that the metre could be lovely after all.

2

During a seminar at the University of Bristol, 26 February 1991. Being of a certain generation and cast of mind, his remark was phrased in the singular and with a masculine reference.

3

Two recent major studies cast complementary lights on it: M. Biddle,

The Tomb of Christ

(Stroud, 1999), and C. Morris,

The Sepulchre of Christ and the Medieval West: From the Beginning to 1600

(Oxford, 2005).

4

II Timothy 3.16.

5

G. Williams,

Recovery, Reorientation and Reformation: Wales c. 1415-1642

(Oxford, 1987), 305-31.

6

D. Dymond, 'God's Disputed Acre',

JEH

, 50 (1999), 464-97, at 465.

PART I: A MILLENNIUM OF BEGINNINGS (1000 BCE-100 CE)

1: Greece and Rome (

c

. 1000 BCE-100 CE)

1

John 1.1-14.

2

All four Gospels use the word 'Christ' as a name for Jesus, although fairly sparingly, with only two instances in the earliest Gospel, Mark (9.41 and 15.32, the latter being in sarcastic speech). The usage is very common in the surviving letters of Paul of Tarsus, which are generally acknowledged to predate the Gospels.

3

O. Murray,

Early Greece

(Brighton, 1980), 13-20.

4

Revelation 1.8, 21.6 and esp. 22.13.

5

J. Dillenberger,

Style and Content in Christian Art

(London, 1965), 34-6.

6

Job 38-42; Exodus 3.13-14.

7

R. G. Collingwood and J. N. L. Myres,

Roman Britain and the English Settlements

(2nd edn, Oxford, 1937), 186.

8

M. I. Finley,

The Ancient Greeks

(London, 1963), 30-53.

9

See esp. I Samuel 28.15-19.

10

See esp. Exodus 18; 34.34-5.

11

For an introduction to 'Tyrants and Lawgivers', see R. Lane Fox,

The Classical World: An Epic History of Greece and Rome

(London, 2005), Ch. 5.

12

The term 'Classical', which I will be employing, is derived not, as is sometimes asserted, from the usage of the Latin word

classis

for 'fleet', but in its meaning of 'first-class heavy infantry': see ibid., 1.

13

I am indebted to Oliver Taplin for these perceptions of Athens:

TLS,

15 September 2006, 5. For the suggestion that Alexandria was crucial in making such choices, see p. 39.

14

R. Warner (tr.) and M. I. Finley (ed.),

History of the Peloponnesian War: Thucydides

(rev. edn, London, 1972), 152 [Bk II, Ch. 46]. The best survey of Greek homosexuality is now J. Davidson,

The Greeks and Greek Love: A Radical Reappraisal of Homosexuality in Ancient Greece

(London, 2007).

15

W. D. Desmond,

The Greek Praise of Poverty: Origins of Ancient Cynicism

(Notre Dame, 2006), esp. 6-7, 60-61, 144; on Diogenes and masturbation, H. Cherniss (ed.),

Plutarch's Moralia

(17 vols., Loeb edn, London and Cambridge, MA, 1927-2004), XIII, Pt II, 501 [

On Stoic Self-contradictions

21]. For 'Holy Fools' in the Christian tradition, see p. 207.