Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years (81 page)

Read Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years Online

Authors: Diarmaid MacCulloch

Tags: #Church history, #Christianity, #Religion, #Christianity - History - General, #General, #Religion - Church History, #History

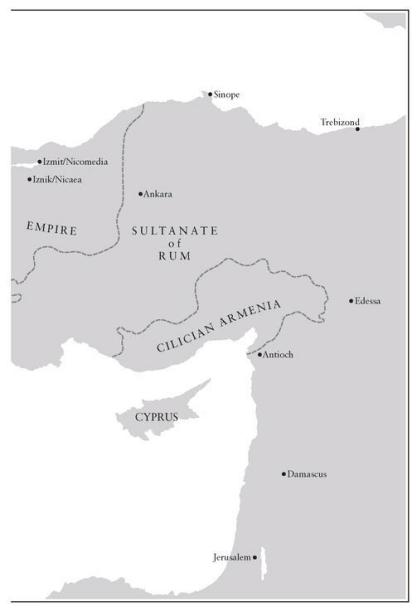

The greater miracle was more gradual: a painstaking reconstruction of Byzantine society, but in a new and unprecedented mould. While the hated Latins still held 'the City', Byzantine leaders would have to rule from other cities of the shattered empire. Far away to the north-east on the Black Sea, members of the Komnenos family took over Trebizond, founding an 'empire' which continued to be independent (initially under Mongol protection against the Seljuks), even beyond the Ottoman capture of Constantinople, until 1461. At the other extreme of the pre-1204 empire, a nobleman related to the old imperial families set up a principality in the region of Epiros on the western Greek coast, but among all these new statelets, the city of Nicaea in the mountains of Asia Minor inland from the Sea of Marmara became the capital of what was the most convincingly imperial of the successor states. It enjoyed the very considerable advantage that a successor Greek Oecumenical Patriarch was installed there, alongside the imperial prince, whom he duly anointed as emperor.

It was eventually the rulers in Nicaea who recaptured Constantinople from the Latins in 1261. Successive popes loudly agitated for aid in restoring the deposed Latin emperor, but they had many other concerns, and the artificial construct of Latin Byzantium had few friends in the West: the Nicaean emperor actually drew on support from Venice's bitter commercial rival Genoa in recapturing the city.

22

A darkly intriguing find in modern Istanbul symbolizes the dead end of the Latin Empire of Byzantium. In 1967 a little chapel was discovered in excavating the lower layers of one of Istanbul's former monastic churches, now the mosque of Kalenderhane Camii. Its interior was filled with earth and its entrance blocked and plastered over with paintings; inside, on its walls were Western-style frescoes of the life of St Francis of Assisi, in fact the earliest now known, complete with the story of Francis preaching to the birds. Evidently when Franciscan friars fled the city, never to return, the chapel with its homage to a very newly minted Western saint was comprehensively consigned to oblivion.

23

One can understand the depth of the feelings which went into that act if we consider the arrogance with which the Greek Church had been treated in some of the new Latin enclaves. In the Latin Kingdom of Cyprus, the suppression of Greek Church organization and general harassment of Greeks who used their traditional liturgy reached a nadir in 1231, when thirteen Greek monks were burned at the stake as heretics for upholding their traditional rejection of the Western use of unleavened bread in the Eucharist, and thus casting doubt on the validity of Latin Eucharists. The fact that this outrage took place during the breakdown of royal Cypriot authority in a civil war among the Latins hardly excuses it, and one can understand why a synod of the Oecumenical Patriarch defiantly denied validity to the Latin Eucharist two years later.

24

And it was during the thirteenth century that yet another issue was added to the sense of theological alienation between Greeks and Latins: the Western Church's elaboration of the doctrine of Purgatory (see pp. 369-70). When friars began expounding this doctrine in various theological disputations in the East, the Greeks with whom they were arguing correctly recognized the origins of the doctrine in the theology of Origen, and that was enough to make Latin talk of Purgatory seem a dangerous reversion to his heretical universalism.

25

Even though Constantinople was restored to Byzantine control in 1261, the empire's political unity, that fundamental fact of Byzantine society from Constantine the Great onwards, never again became a reality. Trebizond and Epiros continued in independence; many of the Latin lords clung on in their new enclaves in Greece, and the Venetians were only finally dislodged from the last of their eastern Mediterranean acquisitions, Crete, in 1669. An emperor was back in his palace in Constantinople, but few could forget that for all Michael Palaeologos's evident talent as military leader, ruler and diplomat, he had supplanted, blinded and imprisoned his young ward, John IV, in order to become emperor. After alienating many influential leaders in the Church and society by this act of cruelty, Michael VIII further infuriated a large number of his subjects by his steadfast pursuit of unity with the Western Latin Church, which he regarded not merely as a political necessity to consolidate imperial power, but as a divinely imposed duty. The hatred which his policy aroused pained and baffled him; the union of the Churches which his representatives carefully negotiated with the Pope and Western bishops at the Council of Lyons in 1274 was repudiated soon after his death.

26

The balance of forces in Orthodox Christianity was never the same again after 1204. Orthodoxy beyond the Greeks could now fully emerge from the shadow of the empire which had once both created and constrained it. King Stefan

Prvovencani

('first-crowned') of the newly emerged state of Serbia first explored what privileges he might get from Innocent III, but he was deeply offended when the Pope changed his mind about granting him royal insignia. Although both Bulgaria and Serbia did eventually receive crowns from the papacy during the thirteenth century, the momentum of Orthodox practice was too strong to pull them back for long into the orbit of Latin Christianity. Both the newly consolidating Serbian monarchy and the Bulgarian monarchs (who were now calling themselves

tsars

, emperors) found it convenient to look to the patriarch in Nicaea for recognition of their respective Churches as autocephalous (self-governing). Mount Athos was a major influence in their turn towards Orthodoxy, and in Serbia the memory of one charismatic Athonite member of the princely family, Stefan Prvovencani's brother Sava, was decisive. As a young man, Sava renounced his life at Court to become a monk on Mount Athos, where he was joined by his father, the former Grand Prince Stefan Nemanja. Together they refounded the derelict monastery of Chilandar (Hilander) on the mountain, and then Sava returned to organize religious life in a Byzantine mould in Serbia, becoming in 1219 the first archbishop of an autocephalous Church of Serbia.

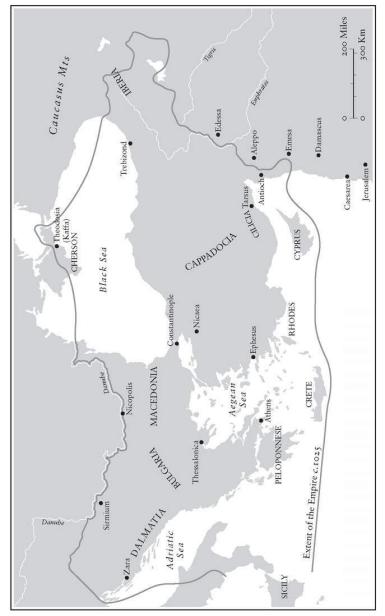

12. The Byzantine Empire at the death of Basil II

Although Sava and his father might be seen as having renounced worldly ambition in turning to the monastic life, their status as churchmen had a vital political effect on their country. The monastery of Chilandar became an external focus for the unity of the Serbian state and a symbol of its links with the Orthodox East. The monarchy did not merely adopt Byzantine trappings of power but ostentatiously rooted out Bogomil heresy from its dominions - while around 1200 for the first time it also encouraged the use of the Serbian language in the inscriptions of Byzantine-style church paintings. Chilandar became the centre during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries for a major enterprise of translating Greek theological and spiritual writings into a formal literary vernacular which would be generally comprehensible to the varied peoples who spoke Slavonic languages. Above all, Sava's immense spiritual prestige gave a continuing sacred quality to the Serbian royal dynasty amid the poisonous divisions of Serbian power politics. His memory became so much part of Serb identity that when the conquering Ottoman Turks wanted to humiliate and cow the Serbs in 1595, they dug up Sava's bones in Belgrade and publicly burned them.

27

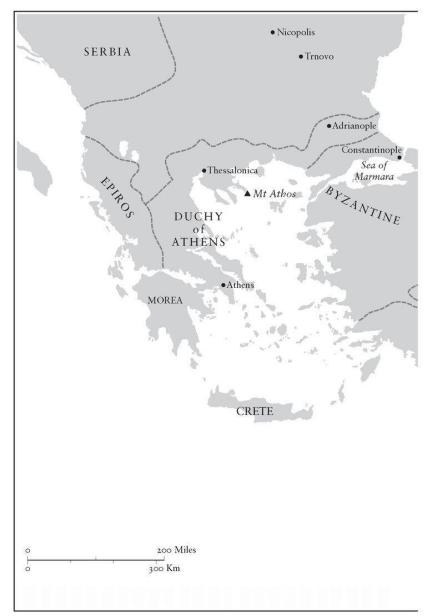

13. The Byzantine Empire reunited under Mickael Palaeologos

ORTHODOX RENAISSANCE, OTTOMANS AND HESYCHASM TRIUMPHANT (1300-1400)

This complex of stories after 1204 amounts to a reconfiguration of Orthodoxy. Certainly the emperors restored to Byzantium in 1261 kept an immense prestige despite their increasing powerlessness, right down to their dismal last years in the fifteenth century. Paradoxically, this was especially so among Melchite (that is, 'imperial') Christians living under Islamic rule and thus beyond Constantinople's control: for them, the emperor was a symbol of an overarching timeless authority, as they believed that God had greater plans for his creation than seemed possible in the present situation.

28

Nevertheless, Orthodox identity was no longer so closely tied to the survival of a political empire, and it was increasingly a matter for the Church to sustain. The Oecumenical Patriarch had been responsible for lending the princely claimant from Nicaea enough legitimacy to claim the imperial throne; that same patriarch had been the source of sacred guarantee for the new ecclesiastical independence of Bulgaria and Serbia, and the patriarch continued to provide his seal of approval to new Christian dioceses expanding far to the north of the imperial borders along the Volga, around the Black Sea and in the Caucasus. By the end of the fourteenth century, Patriarch Philotheos could write to the princes of Russia in terms which would have made Pope Innocent III blanch, although it is unlikely that his words came to the ears of anyone in Rome: 'Since God has appointed Our Humility as leader of all Christians found anywhere on the inhabited earth, as solicitor and guardian of their souls, all of them depend on me, the father and teacher of them all.'

29

This was a strange reversal of fortunes for patriarch and emperor. The patriarch was bolstered by financial support from rulers beyond the old imperial frontiers who were impressed at least by the resonance of such claims. The magnificence and busy activity of the patriarchal household and the Great Church in Constantinople looked a good deal less threadbare than the increasingly curtailed ceremonial and financial embarrassment of the imperial Court next door.

30

Churches were lavishly redecorated or rebuilt, and they were hospitable to an adventurous renaissance in Byzantine art. Some of the most moving survivals are to be found in the church of Istanbul's Church of the Holy Redeemer in Chora, an exquisite monastic building lovingly restored from ruin after the expulsion of the Latins in 1261. Now its mosaics are exposed once more after their oblivion in the church's days as a mosque. Most are from the fourteenth century, and they bring a new quest to explore their subjects as human beings of passion and compassion; even Christ and his mother are softened from the imperial figures of earlier Byzantine convention (see Plate 22). We glimpse at the Holy Redeemer in Chora how Byzantine artists might have continued to explore some of the directions which an artistic and cultural renaissance began to take in Latin Europe in the same era, if the politics of the eastern Mediterranean had not curtailed the urge or the opportunity to consider new possibilities for Orthodox culture.

Over the early fourteenth century, the empire briefly revived after 1261 descended into renewed civil war and loss of territory, both in the west to the expansionist Orthodox monarchy in Serbia and in the east to a new branch of Turkish tribes who had carved out for themselves a principality in north-west Asia Minor and who survived a determined effort by the Byzantines to dislodge them in a significant victory in 1301. Their warlord leader was called Osman, and they took their name of Ottomans from him. During the fourteenth century, the Ottomans extended their power through Asia Minor and the Balkans, overwhelming the Bulgarians and encircling Byzantine territory. More and more Orthodox Christians found themselves under Islamic rule, and in an atmosphere of increasing intolerance for their religion, which might be seen as part of a general cultural mood in fourteenth-century Asia, North Africa and Europe (see pp. 275-8). Already in the 1330s, the shift to Islamic dominance seemed so irreversible that the Patriarch of Constantinople issued informal advice to Christians in Asia Minor that it would not necessarily imperil their salvation if they did not openly profess their faith.

31