Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years (90 page)

Read Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years Online

Authors: Diarmaid MacCulloch

Tags: #Church history, #Christianity, #Religion, #Christianity - History - General, #General, #Religion - Church History, #History

Around 1560 Ivan's reign took a dark turn amid growing political crisis. The death of his first wife, whom he seems to have loved genuinely and deeply, was soon followed by the death of his brother and of Metropolitan Makarii. There was plenty in Ivan's previous career to anticipate the violence which he now unleashed, but the scale of it all was insane, worthy of the ancestors of the Tatars over whom he had triumphed - his second wife was indeed a daughter of one of the Tatar khans. Novgorod, once the republican alternative to Moscow's monarchical autocracy, especially suffered, with tens of thousands dying in a coldly calculated spree of pornographic violence. The Tsar's agents in atrocity, the

oprichniki

, were like a topsy-turvy version of a religious order: as they went about their inhuman business, they were robed in black cloaks and rode black horses, to which with equally black humour they attached dogs' heads and brushes to announce their role as guard dogs and cleansers. After 1572, Ivan abandoned the experiment in government by the

oprichniki

which had created this nightmare, but at his death, in 1584, he still left a country cowed and ruined.

As he rounded in turn on his

oprichniki

in 1573, the Tsar wrote a letter of bitter repentance (or dictated it - contrary to a long Russian historiographical tradition, it is not certain whether he was literate); it was addressed to the Abbot of Beloozero, one of the monasteries for which he had particular reverence. He threw himself on the mercy of the Church: 'I, a stinking hound, whom can I teach, what can I preach, and with what can I enlighten others?'

59

In the last phase of his reign, the Tsar poured resources into new monastic foundations in what is likely to have been an effort to assuage his spiritual anguish (exacerbated by his murder of his own son in 1581), confirming in his generosity the victory of the 'Possessors' in the Church. Yet his terror against a variety of hapless victims continued. Did he think that he was purging his people of their sins by the misery which he was inflicting on them? As his latest biographer sadly comments, echoing earlier Russian historians, he had become 'Lucifer, the star of the morning, who wanted to be God, and was expelled from the Heavens'.

60

This ghastly latter-day caricature of Justinian needed no Procopius to expose his crimes; they were there for all to see, with little more than his own attempt in Red Square at rivalling Justinian's Hagia Sophia to mitigate their dreadfulness.

In the reign of Ivan's son and successor, Feodor (Theodore) I, the Church of Muscovy gained a new title which mirrored the dynasty's assumption of imperial status; it became the Patriarchate of Moscow. The occasion was an unprecedented visit to northern Europe by the Oecumenical Patriarch Jeremias II, desperate to raise money for the Church of Constantinople. When Jeremias eventually reached Moscow in 1588, he was given a fine welcome, but after nearly a year of entertainment, it became clear to him that his parting might be even more considerably delayed if he did not give his blessing to a new promotion for the metropolitan to patriarch. Jeremias agreed: after all, his involvement in conferring this honour was a renewed acknowledgement that, like his predecessors in the fourteenth-century contests between Lithuania and Muscovy, he had the power and ultimate jurisdiction which made such decisions feasible.

One near-contemporary account of what happened suggests that Jeremias signed the document establishing the Moscow patriarchate without any clear idea of what it contained. This would have been just as well, since the text of it goes straight back to Filofei's letter to Vasilii III in describing the Russian Church as the Third Rome. It echoes Filofei's idea that Rome had fallen through Apollinarian heresy, while the Second Rome was now 'held by the grandsons of Hagar - the godless Turks. Pious Tsar!', it continues, 'Your great Russian empire [

tsartvo

], the third Rome, has surpassed them all in piety.'

61

If someone did actually translate this for him, Patriarch Jeremias would have to disregard the implied insult to the patriarchate of Constantinople and appreciate realities: Moscow was the only centre of power in the Orthodox Church which was free of Muslim rule. Moreover, another image of the new patriarchate would be in his mind. Regardless of whether it called itself the Third Rome, the Church of Moscow could be regarded in another light; looking to the five great patriarchates of the early Church, it could be seen as the replacement for one of the five, the now apostate patriarchate of Rome.

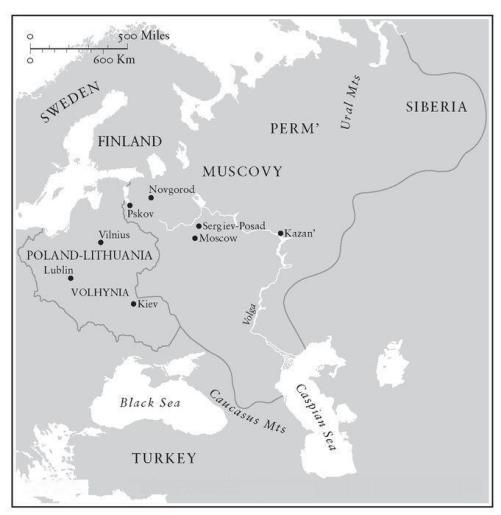

15. Muscovy and Eastern Europe after the Death of Ivan IV

This was a very important consideration in 1589, for both secular and ecclesiastical power politics were building up to a major clash in eastern Europe. As in the past, the background was the confrontation between Poland-Lithuania and Muscovy. The Jagiellon dynasty of Poland-Lithuania had built on their fourteenth-century manoeuvres to become one of the most successful political enterprises in eastern Europe, and particularly after Ivan IV's pathological wrecking of his own land, Poland-Lithuania's future looked very promising. In 1569, prompted to seek greater security by recent savage but inconclusive wars with Ivan IV, the Polish and Lithuanian nobilities - Catholic, Ruthenian Orthodox and Protestant - reached an agreement at Lublin with the last Jagiellon king, Sigismund II Augustus, to create a new set of political arrangements. Instead of a loose union dependent on the person of the king and his dynasty, there would be a closer association between the kingdom of Poland and the Grand Principality of Lithuania, in a Commonwealth (

Rzeczpospolita

in Polish) which would command greater resources and territory than any of its neighbours, and which carefully safeguarded the rights of its many noblemen against the monarchy. Such a vast unit included an extraordinary variety of religions, and it had done so even before the sixteenth-century Reformation had fragmented Western Christianity.

Given the commanding political position of the nobility, principally thanks to the fact that it would now collectively choose the monarchs of Poland-Lithuania by election, it was impossible to impose uniformity on the patchwork of the Commonwealth as many Western political authorities were trying to do, with varying degrees of success. Indeed, by the Confederation of Warsaw of 1573, the nobility extracted from a reluctant monarchy an enshrined right of religious toleration for nearly all the varieties of religions established in Poland-Lithuania, Lutheran and Reformed, even anti-Trinitarian Protestants (see pp. 643-4). In both halves of the Commonwealth, Protestantism made strong advances in the 1560s and 1570s, but mostly in a restricted social sphere of landowners and prosperous and educated people. By contrast, below that level, the vast mass of the population spread through the plains and forests remained little affected by these lively new movements. In the west of the Commonwealth that meant that they persisted in their Catholicism, while in the east, the Ukraine and Volhynia and much of Lithuania, they were mostly Ruthenian Orthodox. Even though King Sigismund Augustus and his successors of other dynasties were convinced Catholics, and welcomed the renewal of Catholicism which the Society of Jesus was bringing to their dominions from the 1560s (see pp. 678-9), they could see that there was still much potential advantage for the ruler of the Commonwealth in claiming to be the successor of Kievan Rus' rather than the new Orthodox tsar in Muscovy. How might the situation be resolved?

Of all the competitors for the religious allegiance of the population in the late sixteenth century, the Ruthenian Church was in most disarray. Disadvantaged by the Catholicism of its monarch (and so, for instance, forced against its will to accept the new calendar sponsored by Pope Gregory XIII in 1582), it was politically estranged from Moscow by political borders, looking instead to an independent metropolitan in Kiev, while its contact with the patriarch in Constantinople was almost non-existent. It had no equivalent of the revivalist movement of the Jesuits; it lacked the fierce commitment to preaching and theological argument in print which was the hallmark of both Lutheran and Reformed Protestantism, and the language of its liturgy and devotion was Old Church Slavonic, which, despite its ancient contribution to rooting Christianity in Slavic lands, now managed to be both increasingly regionalized in usage and remote from the Slavic language of ordinary people. Wholly exceptional was the achievement sponsored by the cultured and far-sighted Prince Konstantyn Ostroz'kyi, the most prominent nobleman of the Commonwealth still loyal to Orthodoxy: he founded an institute of higher learning at his chief town of Ostroh in western Ukraine, and in 1581 sponsored the printing of a Bible in Church Slavonic.

62

It was not unexpected, then, that overall morale was low among the Ruthenian hierarchy. Perhaps surprisingly, it was not improved by that momentous journey of Patriarch Jeremias II to northern Europe in 1588-9. On his return from Moscow through the Ruthenian lands, anxious to assert his position in the light of the new arrangements for a patriarchate in Moscow, Jeremias alarmed the local bishops by reminding them of the powers of the Oecumenical Patriarch. As he demonstrated, these included weeding out and defrocking those clergy who had been twice married: those dispossessed numbered in their ranks no less a figure than Onysyfor, the Metropolitan of Kiev. Catholics noted the discontent with interest - the Ruthenian Bishop of L'viv begged his Catholic counterpart in 1589 to 'liberate [our] bishops from the slavery of the Patriarchs of Constantinople'.

63

Within seven years, the Polish-Lithuanian King Sigismund III had concluded a deal with the majority of Ruthenian bishops, and in 1596 the Ruthenian Bishop of Brest (himself also a great magnate and former castellan of the city, brought up as a Reformed Protestant) hosted an agreement on union. The model was the set of agreements in the fifteenth century around the Council of Florence. These had set up Churches which retained Eastern liturgical practice and married clergy, but which were nevertheless in communion with the pope and accepted his jurisdiction and the Western use of

Filioque

(see p. 276). Such Churches have often been referred to as 'Uniates', though generally the Churches of Ruthenian or other Orthodox origin in communion with Rome now prefer to term themselves 'Greek Catholics', the name bestowed on them by the Habsburg Empress Maria Theresa in 1774, to stress their equality of status with Roman Catholicism.

64

Soon every Ruthenian diocese was headed by a bishop who accepted the Union of Brest, and there were hardly any dissident Orthodox bishops left in the Commonwealth. Nevertheless, the union faced problems from the beginning. Prince Ostroz'kyi had long cherished a vision of overall reunion of East and West, including the Protestants, with whom he had excellent relations, but he was infuriated by the terms which the Catholics laid down, since they gave no role to the Oecumenical Patriarch. In an open letter written even before the final deal was signed, he condemned 'the chief leaders of our faith, tempted by the glories of this world and blinded by their desire for pleasures' and menacingly added, 'When the salt has lost its savo[u]r it should be cast out and trampled underfoot.'

65

Passions ran very high: in 1623 the combative-spirited Greek Catholic Archbishop of Polock, Josaphat Kuncewicz, was murdered because, among other affronts, he had refused to allow Orthodox faithful who rejected the union to bury their dead in the parish graveyards which the Greek Catholics had taken over. Twenty years later the Pope declared him a martyr and beatified him; he is now a saint.

66

Meanwhile, as the Church of the Union fissured, in 1632 the Polish monarchy had given in to reality. A new king, Wladyslaw IV, needed both to secure his own recognition from his elector-nobles and to consolidate the loyalty of his subjects in the face of a Muscovite invasion. To the fury of Rome but to the relief of moderates on both sides, he recognized the independent Orthodox hierarchy once more in 'Articles of Pacification'. From now on there were two hierarchies of Ruthenian Orthodox bishops side by side, one still Greek Catholic and loyal to Rome, the other answering to a metropolitan in Kiev in communion with Constantinople.

67

The Orthodox Metropolitan of Kiev newly elected after this agreement in 1633 was a happy choice: Peter Mohyla. He came from one of the leading princely families in Moldavia, beyond the Commonwealth's borders to the south. With a Hungarian mother and experience of university study in France at the Sorbonne, he had the wide vision which the Orthodox Church of Kiev needed at this time. Like Prince Konstantyn Ostroz'kyi before him, he cherished the hope that there could be a true union of Churches which would go beyond what he saw as Roman aggression: the Union of Brest, he remarked tartly, 'was not intended to save the Greek religion but to transform it into the Roman faith. Therefore it did not succeed.'

68

Mohyla's vision was of a Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth which would become the supporter of a newly invigorated Orthodoxy: he was decidedly cool towards Muscovy and the claims of the patriarch in Moscow. He knew a great deal about Western Catholicism, and although he was especially familiar with the contemporary methods and writings of the Society of Jesus, he also produced a translation into contemporary literary Ukrainian of that Western devotional classic of the fifteenth century, Thomas a Kempis's

Imitation of Christ

, adapting it to his own Orthodox concerns, and diplomatically concealing the name of the original author to avoid the wrath of his Orthodox fellow clergy.

69