Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years (92 page)

Read Christianity: The First Three Thousand Years Online

Authors: Diarmaid MacCulloch

Tags: #Church history, #Christianity, #Religion, #Christianity - History - General, #General, #Religion - Church History, #History

Patriarch Adrian died in 1700, after which his office remained vacant until, in 1721, Peter undertook a major reorganization of Church leadership which concentrated all its power in his hands. True to his Westernizing agenda, Peter had built up a team of clergy who had trained in Kiev at the Mohyla Academy, and it was one of their number, Feofan Prokopovich, made Bishop of Pskov, who drew up the new scheme of government, with the aid of advisory memoranda to the Tsar from a much-travelled English lawyer of mystical High Church Anglican outlook, Francis Lee. Prokopovich's own outlook can be gauged from the contents of his library of around three thousand books, three-quarters of which were of Lutheran origin.

81

Instead of the patriarch's rule, there would now be a twelve-strong 'College for Spiritual Affairs', presided over by an official appointed by the tsar, the chief procurator. It was reminiscent of the state-dominated Church government which had been in place in some Lutheran princely states of the Holy Roman Empire for the previous two centuries, but it was far more restrictive, since only the chief procurator could initiate business in the college.

When the College for Spiritual Affairs first met in 1721, the bishops present protested that its name was unprecedented in Russian Church history, and the Tsar was happy to give it a more resonant name which nevertheless in no way changed its nature or function: it became entitled the Holy Synod. While some of those who presided over the Holy Synod in the next two centuries were devout members of the Church (usually in the most darkly authoritarian mould of Orthodoxy), some had little religious belief, or, in the fashion of the Western Enlightenment, gained more spiritual satisfaction from Freemasonry. This was a source of grief and anger to many in the Russian Church, who came to have an obsessive hatred of Freemasonry partly as a result. Among the monarchs to whom the Holy Synod answered, one of the most long-reigning and effective of Peter the Great's successors was Catherine II (reigned 1762-96), a German princess who, despite her reception into the Orthodox Church, never moved far from her culturally Western and Lutheran background, except to befriend that apostle of Enlightenment scepticism Voltaire (see pp. 800-801). The Church was an organ of government, symbolized by Peter's decree of 1722 which required priests hearing sacramental confessions to disregard the sacred obligation of confidentiality and report any conspiracies or insulting talk about the tsar to the security officials of the state, under severe punishments for non-compliance.

82

It is perhaps surprising that there was not more high-level protest against Peter's enactment of a state captivity for the Church's government, but after the humiliation of Patriarch Nikon and the savage official reaction to the Old Believers in the 1680s, there was little chance of any bishop raising further opposition. The clergy were in any case divided among themselves: there was resentment of the Ukrainian-trained clique around the Tsar, and there was also an increasingly bitter division among the clergy between the 'black' elite of monks, with a superior education and a career pointing towards the episcopate and higher Church administration, and the 'white' clergy, married and serving in the parishes. Peter introduced seminaries for clergy training, an institution familiar in Catholic and Protestant Churches to the west, but here they had a curriculum narrowly focusing on the theme of obedience and the selective version of Orthodox tradition which had survived the upheavals of the seventeenth century. Rarely in later centuries did they win much respect for their educational standards or indeed educational humanity, a reputation not mitigated by the memoirs of many former students. Since the seminaries were only open to the sons of clergy, they contributed very significantly to one of the growing characteristics of the 'white' clergy: they were turning into a self-perpetuating caste, marrying into other clerical families. They had their own culture, for good or ill. They might develop an intense commitment to the clerical vocation, or they might see it as more of a family business than the basis for any individual sense of commitment to a spiritual life. In addition, many of these seminary-trained children could not find jobs in the Church; over-educated, frustrated young clergy sons were to prove one of the hazards of life in nineteenth-century Russia.

83

If anything saved Orthodoxy through its eighteenth-century period of unsympathetic leadership and low clerical morale, it was its profound hold over the lives and emotions of ordinary people, which contrasted with popular attitudes to state power. Russian society was exceptional in contemporary Christendom in the degree of separation between its government and its people. Authority and conformity were the watch-words of both the dynasty and the smallest village, but once local communities had paid their taxes to the tsar, raised troops for his armies, and weeded out troublemakers and criminals, they were left largely to their own devices and to their own traditions of making sense of their often desperately harsh environment.

84

Woven inextricably into their common experience were the practices of religion, perhaps the only area of most people's lives where it was possible to make genuine personal choices. Given the isolation of all Russians from much possibility of foreign influence apart from the tiny proportion who belonged to the elite, that meant some variant on Orthodox belief.

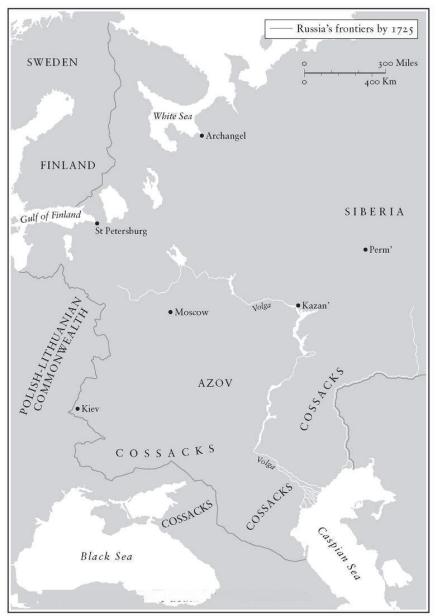

16. Imperial Russia at the death of Peter the Great

Laity who were unhappy at clerical inadequacies and repelled by innovation which could be associated with foreign influences had an alternative in the existing dissidence of the Old Believers, whose numbers and variety swelled during the eighteenth century. They preserved older traditions of worship and devotional styles which the authorities had repudiated, and their rejection of novelty was a rejection of all that they saw as not Russian. Some Old Believers refused to eat the tsars' recommended new staple food, the potato, because it was an import from the godless West - potatoes were generally hated among the Russian peasantry on their first arrival, before their value in making vodka became apparent. 'Tea, coffee, potatoes and tobacco had been cursed by Seven Ecumenical Councils' was one of the Old Believers' rallying cries, and at various times, dining forks, telephones and the railways were to suffer the same anathemas.

85

Sometimes Russian dissidence spiralled off into the most alarmingly eccentric varieties of Christianity ever to emerge from meditation on the divine, usually fuelled by the belief which had once been the mainstay of the official Church, that the world was about to end and the Last Judgement was to come. Towards the end of the eighteenth century, a self-taught peasant leader, Kondratii Selivanov, founded a sect devoted to eliminating sexual lust from the human race. He based his teachings on a creative misunderstanding of particular proof texts in his Russian Bible, reading

Oskopitel'

(castrator) for

Iskupitel'

(Redeemer) when the New Testament speaks of Jesus, and reading God's command to the Israelites as

plotite'

(castrate yourselves) rather than

plodites'

(be fruitful). As a result, his followers, the

Skoptsy

('castrated ones'), cut off their genitals or women their breasts to achieve purity. Despite persecution by the appalled authorities in both tsarist and Soviet Russia, the sect persisted into the mid-twentieth century, when unaccountably it died out, just before the arrival of the permissive era which might have provided it with some justification. The

Skoptsy

were not alone in their self-destructive impulse; in the late nineteenth century, one group of Old Believers, apparently living perfectly peaceably and openly among their neighbours, prevailed on one of their number to bury alive all of them and their children, thus reviving the suicide traditions of the first Old Believers in order to save their souls before the Last Days.

86

Within the official Church, the entrenched traditions of popular Orthodoxy survived the Church's institutional faults; so holy men and women continued to seek stillness in Hesychasm, and to bring what comfort they could to the troubled society around them. Some of the best-loved saints in the Orthodox tradition come from this era. The most celebrated is probably Serafim of Sarov (1759-1833), who lived like Sergei of Radonezh before him in the classic style of Antony. Once, after he had been senselessly attacked and permanently crippled by bandits, he prayed alone for a thousand days, kneeling or standing on a rock. Towards the end of his life he abandoned his solitary existence to strengthen crowds of suppliants daily with his counsel and spiritual pronouncements, like the Syrian stylites long before (see pp. 207-9). 'Achieve stillness and thousands around you will find salvation,' he said.

87

It was in his era that a new Greek collection of classic devotional texts from the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries came to present a sure guide to the forms of prayer in the Hesychast tradition: the

Philokalia

('Love of the Beautiful'), compiled by monks of Mount Athos and first published in Venice in 1782. Only eleven years later, the Ukrainian monk Paisii Velichkovskii produced the first Slavonic translation of this work which became standard in the Orthodox world, and which was a major force in reuniting Orthodox spirituality after the stresses and divisions of the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

At the same time, the expanding Russian Empire gained an international vision for its version of Orthodoxy. It maintained its contacts with Mount Athos, supporting monastic life on the Holy Mountain with a generosity which saw a great flowering of Russian communities there in the nineteenth century. But there was much more to the tsars' intervention in the Ottoman Empire, as it became apparent that the hold of the Turkish sultan on his territories was beginning to weaken. During the eighteenth century, throughout the Orthodox world still ruled by Muslims in the Balkans and the East, Churches began looking with increasing hope to this great power in the north which proclaimed its protection over them, whose Church still announced itself to be the Third Rome, and which pushed its armies ever further into the lands so long languishing in the hands of the Grandsons of Hagar. Soon in its efforts to fulfil its ambitions at the expense of the decaying Ottoman Empire, the Russian Empire would clash with heirs of the Western Reformation, with consequences disastrous for all those drawn into the contest. It is to the West that we now return, to trace the story which led Christendom to the events of 1914.

PART VI

Western Christianity Dismembered (1300-1800)

16

Perspectives on the True Church (1300-1517)

THE CHURCH, DEATH AND PURGATORY (1300-1500)

By the end of the thirteenth century, the Western Latin Church had created nearly all the structures which shaped it up to the Reformation era. Throughout Europe, from Ireland to the kingdoms of Hungary and Poland, from Sweden to Cyprus and Spain, Christians looked to the pope in Rome as their chief pastor. He looked further than that: newly aware of the possibilities of a wider world thanks to the Crusades and the Western Church's thirteenth-century missions into Central and East Asia (see pp. 275-6), the popes made large claims to be the focus of unity in all Christendom. Given the crusaders' failure to recapture former Christian lands except in the Iberian peninsula, these claims remained empty, but within its own world the Church was united by institutions whose ultimate appeal was to Rome: canon law, religious orders, indeed the whole network of parishes, dioceses and archdioceses which made a honeycomb of the map of Europe. European universities, which mostly owed their formal existence to a specific papal grant, embodied in their name their claim to 'universality', the fact that they taught a range of disciplines in a common curriculum embodying a common Latin European culture.

All literate Europeans who owed allegiance to this Church were united by the Latin language which separated the Western Church from its many Eastern counterparts, and which had once been the language of official power in the Roman Empire. Amid Europe's ruins of palaces, temples and monuments surviving from the Classical society digested by Christendom, it was possible to see the Church as the heir of the Roman emperors, but there was another contender, as was clear from a symbolic split in the inheritance of imperial titles between the popes and the monarchs who were heirs of Charlemagne. The Bishop of Rome was

Pontifex Maximus

, the priestly title once appropriated by the Emperor Augustus and his successors and then redeployed by the papacy, while the acknowledged senior among central Europe's princes and cities was an emperor, now calling himself both 'Holy' and 'Roman'. Amid all the symbols of Christian unity, this division symbolized the indecisive results of earlier clashes between popes and monarchs, such as the eleventh-and twelfth-century 'Investiture Controversy' (see pp. 375-6). The campaign to establish a universal papal monarchy had reached its height under Pope Innocent III, but never came close to achieving its aim. It sought a stability in society which could never be attained in practice, and which was mocked by the flux of human affairs. From the eleventh to the thirteenth centuries, the Church had at least been at the forefront of change. After that, the institutions which it had created proved increasingly inadequate to manage or confront new situations; and the outcome was the division of Europe in the sixteenth-century Reformation.