Citizen Emperor (115 page)

Authors: Philip Dwyer

All bureaucrats had to swear an oath of loyalty to Napoleon. Many did, some willingly, some reluctantly. This was the case with one of Napoleon’s most loyal servitors before 1814, the Comte de Molé.

128

He refused to swear an oath of loyalty to the restored monarchy and was kept out of public office as a result. However, he was no more inclined to resume public office when Napoleon summoned him to the Tuileries and offered him a choice of portfolios, justice or foreign affairs. He turned them down, pleading ill-health, and reluctantly took on a position with less responsibility – Director of the Ponts et Chaussées (Bridges and Roads). The whole time he was there, however, he astutely refused to attend important meetings, signed nothing of significance and even sent a letter to Louis XVIII declaring his loyalty. He was so often absent – supposedly sick, travelling to various spas – it is a wonder Napoleon tolerated him at all.

Etienne-Denis Pasquier is another example. A former prefect of police under Napoleon, and Director of the Ponts et Chaussées under the Bourbons, Pasquier refused to adhere to the new government.

129

Friends intervened on his behalf so that he was not arrested. Napoleon tried to purge the administration, nominating his own men, but many refused to take up their positions, so that, for example, some departments remained without prefects, while others again went through four or five in the space of a few months.

130

There was a similar story in the bureaucracy. Administrators were encouraged to denounce their colleagues who had ‘betrayed’ Napoleon, but they simply refused to do so.

131

When the Emperor dismissed all the small-town mayors and held new elections to replace them, 80 per cent of those who had been put in place by the royal government were re-elected. If that was not exactly a slap in the face – there were all sorts of reasons why the mayors were returned – it was certainly a setback for Napoleon, who suffered because of it; he was not in complete control of the administration and hence not in complete control of the country.

132

Among the people of France, the reaction to Napoleon’s return was varied and incredibly complex.

133

It is difficult to get an accurate depiction of public opinion, but it is clear the country was divided along ideological lines. In cities such as Metz, Nevers, Grenoble, Lyons and Paris support for Napoleon seems to have been strong.

134

His followers went to considerable lengths to support the regime and the army. At Grenoble, French pupils at the lycée donated 400 francs, pupils from Nancy 500 francs.

135

Old soldiers offered up their pensions; government officials donated their salaries; women sold their jewels; administrative bodies and cultural organizations throughout France donated tens of thousands of francs. Solidarity was one sentiment, revenge was another. Resentment of the Bourbons in some towns and regions in the south, east and south-east of France led to an urban and rural reaction that often resulted in violence and the murder of royalists.

Support for Napoleon was also expressed in the formation of people’s militias called the

fédérations

, different from the National Guard.

136

It was a spontaneous, popular movement that began in Brittany in the middle of April and spread quickly to the rest of the country. The

fédérations

brought together up to 100,000 men in various regional centres but especially in Paris where 20,000–25,000 men took part in this movement, predominantly motivated by two sentiments: a rejection of the House of Bourbon, and a patriotism born of the impending allied invasion.

137

In some parts of France, those who volunteered were overwhelmingly middle class. In Paris, however, they were largely working class and were based on the faubourgs Saint-Antoine and Marceau. Napoleon felt obliged to promise that he would arm them, but he did not warm to the idea. He was thinking of the

sans-culottes

, who had committed some of the worst excesses during the dark days of the Revolution. But he was caught in a bind. He could not very well suppress the popular enthusiasm that found expression in the

fédérations

, even as he donned anew the mantle of national reconciliation. In the end, they were never armed, even when Paris was about to be besieged by the allies – as we shall see.

138

In other regions, however, the initial enthusiasm for Napoleon’s return quickly waned, as though the people had collectively woken the morning after a drinking binge, regretting what they had done. In the north of France, Marseilles and the Vendée, support for the Bourbons remained constant.

139

In Poitiers, a bust of Napoleon was smashed. In Toulouse, Rouen, La Rochelle, Bayonne and Versailles, royalist proclamations were put up on the wall of the town overnight. In the town of Agde, in the south of France, violence broke out when a new municipal council was proclaimed. The Vendée rose up against Napoleon and in favour of the monarchy on 15 May, largely as a result of the renewed demands for men for war. In the other major urban centres – Bordeaux, Marseilles, Nîmes – royalists dug in their heels and had to be defeated militarily before control of those regional centres could be gained.

140

The pacification was at best fragile when it did occur. Some regions held out longer than others. The Vendée, for example, tied up 8,000 troops and cavalry, as well as part of the Young Guard. In all, more than 20,000 troops were occupied throughout the country putting down the internal flames of rebellion,

141

all of whom could have been put to better use at Waterloo.

26

‘Venality Dressed in Ideological Garb’

Once installed in the Tuileries, Napoleon knew he could not simply take up where he had left off. Before Elba, he had been in undisputed command. After the first abdication, the French were given a charter that granted them a constitutional monarchy; anything less than that now would be unacceptable.

1

Napoleon, therefore, had to present the French people with the façade of himself as a liberal, and one way of doing that was to give them a new, more liberal constitution.

The man Napoleon chose to write a new constitution was Benjamin Constant. For most of his career as a writer, Constant had opposed the Napoleonic system, publishing in 1813

De l’esprit de conquête

(The spirit of conquest), in which he attacked what he considered to be the cornerstone of imperial ideology – Napoleon’s love of war and conquest. He insisted that Napoleon had come closer to achieving total control over his subjects than any other previous ruler. The Emperor had, in effect, usurped the Revolution and the principle of popular sovereignty. As late as March 1815, after hearing news of Napoleon’s return, he published a vicious personal attack on him in the

Journal des Débats

, describing him as ‘more terrible and more odious’ than Attila and Genghis Khan.

2

He also pompously declared, ‘I am not the man to crawl, a miserable traitor, from one seat of power to another. I am not the man to hide infamy by sophisms, or to mutter profane words with which to purchase a life of which I should feel ashamed.’

In fact, he was. When Constant met Napoleon on 14 April after being summoned to the Tuileries, he wrote in his diary that he thought him ‘an astonishing man’. Napoleon had persuaded him to help prepare a new constitution, a fact that is a remarkable testament to his ability to charm even the staunchest opponent (or to Constant’s overwhelming egotism and desire for political office). A few days later, Constant was appointed to the Council of State, and over the coming weeks and months became a confidant of the Emperor. During this time he wrote what was to become known as the Additional Act, an amendment to the imperial Constitution which introduced a number of changes: the recognition that sovereignty resided in the nation; greater independence for the judiciary; limited political representation; and freedom of the press. There were to be elections to a lower house, the Chamber of Representatives, but voting rights were limited to men who owned property and who were at least twenty-five years old. Napoleon appointed members to a new Chamber of Peers, much to the disgust of liberals and revolutionaries, who argued that this was a return to the

ancien régime

. Some of Constant’s enemies claimed that the amendments were ‘venality dressed in ideological garb’.

3

To those in his entourage Napoleon is supposed to have boasted that he would have done with this ‘vain chatter’ within six weeks.

4

Freedom of the press was a case in point.

5

Although royalists were able to vent their rage against Napoleon, especially in the form of pamphlets, censorship was introduced and the police raided royalist presses, both clandestine and legal, for being ‘incendiary’.

There was, moreover, an inherent contradiction between what Napoleon set out to do – that is, introduce a liberal constitution that would win over bourgeois and enlightened opinion – and what the circumstances of the moment required, namely, a firm leader who could bring about a decisive military victory. Rather than consult with those most directly concerned, or have an elected national assembly draw up a new constitution (something that would have taken too long), Napoleon made sure he retained complete control over the whole process. As always, he wanted to be the master, but since no one believed that he would adhere to the Additional Act for long, when it was released to the public on 23 April it was greeted with scepticism.

6

The existence of a hereditary peerage, for example, contradicted the principles of equality demanded by the Revolution. Constant wrote in his journal that ‘Never was blame so bitter, never was censure so unanimous.’

7

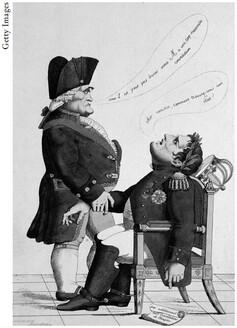

A cartoon in a liberal newspaper aptly illustrated their concerns. It shows Napoleon undergoing a medical examination by Cambacérès. When Napoleon asks, ‘Dear cousin, what do you think of my state?’, Cambacérès replies: ‘Sire, this cannot last. Your Majesty has a very poor Constitution.’

The Constitution was, in short, badly received in France, unable to please any of the political factions. Even though it was more radical than the Bourbon Charter, liberals disliked being handed a constitution they had no part in shaping; republicans bemoaned the fact that it was not more ‘revolutionary’ and that it negated the principle of universal suffrage.

8

Bonapartists hardly saw the necessity of an Additional Act and believed Napoleon should govern as a dictator and that he should have dispensed altogether with elected assemblies.

9

Royalists, needless to say, rejected the whole exercise because it excluded any possibility of a return of the Bourbons. Indeed, there was a stream of critical pamphlets, some by those who had initially greeted Napoleon’s return, but most by royalists who continued to see him as the ‘usurper’.

10

The real problem was that Napoleon did not really believe in the new Constitution, and did not want the elite (certainly not the French public) discussing its terms. There was an evident contradiction in his private and public rhetoric that belied his true intentions. In reality, he did not care for a constitution that limited his powers in any way. In this, the accusation often levelled at émigrés is apposite for Napoleon; during his absence, he had neither learnt nor forgotten anything.