Citizen Emperor (21 page)

Authors: Philip Dwyer

The purge did not entirely eliminate opposition to Bonaparte, which continued, but it was timid and limited. After a while, those who stood on principle usually gave up trying and retired from public life. Cabanis is an example.

102

He was one of the Ideologues who had supported Brumaire and a strong executive as the best means of assuring democracy, and who had been given a position in the Senate as a reward. But increasingly he became disillusioned with the way in which Bonaparte co-opted power. Every now and then he would dare to criticize the First Consul, indeed he was one of the few who did, and occasionally he would cast a negative vote in the Senate. But that is as far as his opposition went. He eventually turned away from public life to pursue private scholarship, giving vent now and then in private to his feelings against Bonaparte and later Napoleon.

103

Bonaparte faced grumblings from staunch republicans and the Ideologues over the Concordat, but he also had to face refractory elements within the clergy – as we have seen, thirty-seven bishops refused to resign from their sees as they were required to by the treaty – and within the army.

104

Despite this, the Concordat was an overwhelming success in garnering support for the regime. The treaty and many of the religious institutions put in place under Bonaparte had but one objective – for the state to regain control over the religious question and to heal the social rift that had occurred during the Revolution. Bonaparte would now have at his disposal a corps of ‘prefects in purple’ who could help him extend his power over the French, but no more so, it has to be said, than the former kings of France.

105

If Bonaparte was able to write to his uncle, Cardinal Fesch, ‘The Concordat is not the triumph of any one party, but the reconciliation of all,’

106

it was because the agreement with the Church deprived royalists and the counter-revolutionaries of their most powerful ammunition. Religion had been a fundamental factor in the revolts in the Vendée and in the Midi; the Concordat solidly placed the Church on the side of Bonaparte and the Consulate.

The Concordat was by no means perfect, nor indeed had the whole of French society been reconciled to the regime and to Bonaparte. For the moment, however, it enabled Catholics to rally to a ‘monarchical plebiscitary republic’. Leading ecclesiastics helped this process by depicting Bonaparte as a providential man, placed by God at the head of France, in the same way Cyrus, Constantine and Clovis had once been placed by God at the head of their people.

107

Religion was to become one of the foundations of the new regime and of Bonaparte’s political legitimacy. In signing the treaty with Pope Pius VII, he assumed the same rights and prerogatives towards the Catholic Church as the former kings of France.

108

In the eyes of the pope, therefore, he held his power from God. The state, Bonaparte and religion were increasingly intermixed. According to article 8 of the Concordat, for example, mass was to end with the following prayer: ‘O Lord, save the Republic; O Lord, save the consuls’ (

Domine, salvam fac rempublicam; domine, salvos fac consules

).

109

It wasn’t long before the word ‘consuls’ was replaced with ‘consul’.

Portraying Bonaparte

The peace treaties and the Concordat were fully exploited by the regime, and reinforced the reputation gained by Bonaparte in Italy as a warrior who despised war and who offered peace to vanquished enemies.

110

The religious and military peace enabled Bonaparte to conquer areas of public opinion that had not yet come over to the regime.

111

Much of what we see in the press during this period is about France returning to the ‘European family’, while the artistic representations of Bonaparte during this period also played to this theme. For example, a competition was organized under the auspices of Lucien’s successor as minister of the interior, Jean-Antoine Chaptal, calling on artists to celebrate the Peace of Amiens and the re-establishment of religious cults.

112

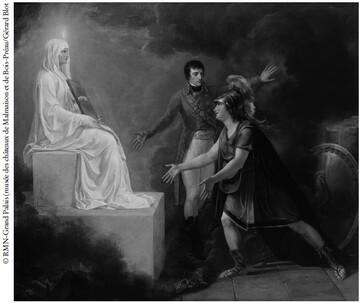

Anonymous,

Allégorie du Concordat

(Allegory of the Concordat), 1802. Bonaparte appears to be parting the darkness in order to reveal religion, bathed in light, to France. This painting was probably the result of a competition that was held in 1802.

The results were mediocre. The director of the Central Museum of the Arts, Dominique Vivant Denon, was so disappointed by the absence of submissions from the great artists, and by the pedestrian quality of those paintings submitted, that he recommended the regime abandon altogether the use of competitions for art works.

113

The government consequently thought through the manner in which the regime interacted with artists. From the beginning of 1803, artistic competitions were mostly replaced by the commissioning of works of art from chosen artists.

114

This gave the regime a great deal more control over what was portrayed, but it also provided Bonaparte with much greater say in how he and his accomplishments were represented: he ordered at least ten portraits in 1803 alone from artists who included Jean-Antoine Gros, Jean-Baptiste Greuze and Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres.

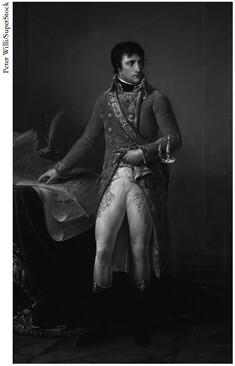

A typical example of a Bonaparte portrait for this period, replete with the symbols that allowed the onlooker to interpret the painting’s political message, is Gros’

Bonaparte, Premier Consul

(Portrait of the First Consul). Bonaparte ordered four copies for presentation to a number of important towns.

115

Indeed, the regime was behind a concerted effort to place his image in public buildings where for the last ten years only allegories of Liberty or the Republic had been on display.

116

The symbolism in the painting was evident to contemporaries. On a table covered with a brocaded cloth lie a number of parchments, one of which listed the treaties that had been signed by Bonaparte. Bonaparte is pointing to the word ‘Lunéville’, underlining the point that it was a precondition of the Peace of Amiens, but also that he had defeated the Second Coalition.

117

In this manner, he is being presented as an energetic and decisive leader, but more importantly as the bearer of peace, in stark contrast to the inept regimes that had preceded him.

118

Gros’ painting became the prototype of the official portrait of Bonaparte – in half-civilian, half-military costume – but it also falls within the French tradition of portraying monarchs in what might be called a ‘royal posture’ of the king as bearer of peace, which had been present from Louis XIII through to Louis XVI.

119

Gros’ painting thus linked Bonaparte to past monarchs. The only difference at this stage is the absence of the attributes of power, such as a globe or the hand of justice. The best sculptors were likewise engaged by the state to carve representations of Bonaparte. Two of the best-known busts are by Antonio Canova and Antoine-Denis Chaudet, both commissioned in 1802, both done in a Greco-Roman style, with hundreds if not thousands of cheap copies made in plaster of Paris that could be found on ‘every gingerbread stall’ in Paris.

120

Even at this early stage, enterprising entrepreneurs cashed in on the mania around Bonaparte by producing his image on just about anything they could get away with, including barley sugar in the form of Bonaparte’s head.

Antoine Gros,

Bonaparte, Premier Consul

(Bonaparte, First Consul), 1802. Bonaparte’s face is a copy of the Arcola portrait.

This helps us understand the point towards which we are now heading – the foundation of the Empire. A number of Bonaparte’s portraits are modelled on monarchical representations of

ancien régime

kings, minus the glitz and glamour. His portraits are more austere – he was ruling a republic after all – and there is certainly nothing pretentious about them, but they are nevertheless monarchical for all that, containing many of the qualities of princely portraits. This will naturally become more pronounced with the onset of the Empire, as Bonaparte made a concerted effort to distance himself from the Revolution and to develop links with the Catholic monarchies of Europe. But for the moment there is a disarming, almost Spartan simplicity about them, more in keeping with revolutionary than later imperial iconography.

121

It is their simplicity that contributed towards forging, as well as popularizing, Bonaparte’s image. That image was nothing more than an artificial creation meant to enhance both his reputation and his career. But here is the rub: Bonaparte at first identified with the image, and then began to assume and believe in it so that eventually the artificial creation took over and became the character. As for the reception of his portraits, it necessarily differed depending on where the onlooker’s political tendencies lay, or whether the onlooker was a Frenchman or a foreigner.

122

Two things can be said with a degree of confidence. Within a year of the coup, through newspapers and popular prints, Bonaparte and the Consulate became one. Bonaparte, although perceived differently by different people, became at one and the same time the victorious general, the man of providence, the Saviour of the Revolution and the man of peace.

123

The perception was more than the result of a successful propaganda campaign; it was based on the real accomplishments of Bonaparte and his collaborators, reinforced by the manner in which those achievements were portrayed.

If the iconography depicting Bonaparte before he came to power had a limited audience, after Brumaire he was able to reach out to many more people. One way of doing this was through the Paris Salon. The Salon had been initiated in Paris in 1725 and was held in the Grand Salon or the Salon Carré of the Louvre.

124

Artists were invited to exhibit their work, and were thus seen to be in favour with the king. Once a jury and prizes were introduced in the middle of the eighteenth century, it became

the

major event of Parisian artistic life and one of the most effective ways for artists to earn a reputation. From 1804, the Salon took place every two years, and was judged by a jury of six artists named by the government. For the regime, however, the Salon was much more than an artistic exercise. It was a means of getting a particular message across to a wide audience. The Salons were popular – they attracted up to 100,000 visitors – and since they were free one could encounter a cross-section of Parisian society.

125

More often than not the themes that were treated in the Salon were no longer current. Unlike popular engravings, which were often spontaneous, immediate reactions to an event, the works displayed at the Salon usually took a number of years to complete. Catalogues accompanied the exhibition and sometimes gave detailed descriptions of the paintings, especially for historical subjects. The descriptions were sometimes so detailed that they constituted history lessons in themselves. It is easier to understand Gros’ painting in that context, as part of a concerted effort to overcome Bonaparte’s two-dimensional figure as military hero and victorious general and to create an image more in keeping with his new role. Bonaparte himself had always understood that power was above all civilian.

126

After Brumaire, and within a short space of time, the victorious, young, republican hero virtually disappeared and was replaced by a far more reflective, more mature (gone is the long hair of his youth), more meditative image of the responsible statesman, legislator rather than warrior. Bonaparte was now portrayed presenting treaties, giving a constitution, establishing the Concordat, preparing the Civil Code or installing himself in the Tuileries. As we shall see, he even managed to appropriate the role of the enlightened legislator.

127

This does not mean, however, that military exploits were no longer celebrated. On the contrary, battle paintings continued to be produced at an ever-greater rate. One of the strengths of Napoleonic iconography was its ability to touch people’s hearts in a simple manner; the emphasis was on realism. At the Salon of 1802, the largest crowds gathered around paintings of Marengo.