Citizen Emperor (22 page)

Authors: Philip Dwyer

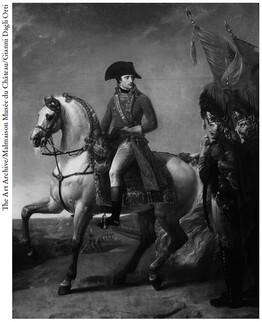

Antoine-Jean Gros,

Portrait équestre de Bonaparte, Premier consul, à Marengo

(Equestrian portrait of Bonaparte, First Consul, at Marengo), 1803. Bonaparte is seen here giving out a sword of honour to the grenadiers of the Consular Guard after the battle of Marengo. It is a tellingly different image of Bonaparte, despite the face being recycled from Gros’ painting of Arcola, for he is looking down on his soldiers from atop a horse. Gone are any egalitarian trappings.

128

6

‘The Men of the Revolution Have Nothing to Fear’

The reverberations of the Peace of Amiens were to have profound consequences for the direction politics would take. A number of people in Bonaparte’s entourage – Lucien and Talleyrand among others – wished to see the First Consul’s powers extended, although we do not know who came up with the idea of prolonging them indefinitely. We know that Bonaparte too was thinking along these lines, although he would not say so publicly. Rather than officially ask for anything for himself, he was in the habit of working behind the scenes to have honours ‘offered’ to him. Even though a number of discussions had taken place between him and the other two consuls, as well as with a number of tribunes and senators,

1

it is likely that he and his entourage only ever insinuated, never clearly stated, what they had in mind. There was, moreover, some discussion of these issues in the press. Roederer published a thin pamphlet entitled

Un citoyen à un sénateur

(A citizen to a senator), in which one could find a plea for giving Bonaparte the time necessary to accomplish his great oeuvre.

2

These manoeuvrings no doubt resulted in the vague idea, which began to circulate in the spring of 1802, that the legislature should offer some sort of recompense to Bonaparte for his achievements.

On 6 May, Cambacérès sent for the president of the Tribunate, Georges-Antoine Chabot de l’Allier, and informed him that it would be appropriate if the Tribunate used its powers to ‘express a wish that would be agreeable to the First Consul’.

3

Just what that wish should be was left to the Tribune’s imagination. Chabot de l’Allier went away thinking of a modest recompense like the title ‘Pacificator’ or ‘Father of the People’,

4

and seems not even to have thought of granting Bonaparte the consulship for life. When Chabot spoke before the Tribunate that same day, he asked that the First Consul be given a ‘grand recompense’, and urged the Tribunate to express the will of the people by proposing that Bonaparte be accorded ‘a dazzling sign of the Nation’s gratitude’.

5

The Tribunate adopted the proposal unanimously, but the phrase was so ambiguous that it has been interpreted as a blatant evasion, proof that the Tribunate was determined not to extend Bonaparte’s already extensive powers.

6

It was left to the Senate to do so. On 8 May, Bernard-Germain de Lacépède, a slavish follower of Bonaparte,

7

proposed that the First Consul’s tenure be extended for another ten years. The proposal was debated and eventually carried, sixty votes to one. Men like Fouché, Grégoire and Sieyès, united in their dislike of Bonaparte, had been working behind the scenes to persuade the senators against the idea of giving Bonaparte more than an extension of ten years and had won the day.

8

General François-Joseph Lefebvre, the former commandant of Paris who had played an important role during the coup of Brumaire, brought the news of the Senate’s decision to Bonaparte thinking he would be pleased with the outcome. He was not.

9

Cambacérès had to calm him down, and that evening, along with Joseph and Lucien who had joined their brother in his office, Cambacérès proposed another expedient – to overlook the Senate’s decision by appealing directly to the people. In a reply to the Senate, through Cambacérès, Bonaparte maintained that ‘The vote of the people invested me with the supreme Magistracy. I could not feel myself assured of their confidence unless the act that kept me in office was yet again sanctioned by its vote.’

10

This veiled threat was read the next day to a delegation of senators who had come to congratulate Bonaparte on his extension of power for another ten years. That same day Bonaparte departed for Malmaison; he had decided to leave the political manoeuvring to Cambacérès.

Before holding another plebiscite, however, Bonaparte wanted to know the opinion of the Council of State; he hoped to obtain the approbation of this institution and use it in his struggle with the Senate. An extraordinary session was held on 10 May with Cambacérès, Lebrun and all the ministers (except Fouché) present. Thibaudeau, without whom the role of the Council of State in this whole affair would have remained obscure, described the session.

11

During the meeting, one of the architects of the Civil Code, Félix-Julien-Jean Bigot de Préameneu, briefed beforehand by the Second Consul, argued that ‘the people had to be consulted in the forms established for all elections’, and that therefore the vote of the nation could not be restricted to the ten years suggested by the Senate. The Council of State was obliged to ask the people of France whether or not the First Consul should be elected for life.

12

The underlying argument was that they had to give the government stability and this could not be done by an extension of another ten years. We know that at this meeting Cambacérès declared that if a perpetual extension of Bonaparte’s powers was necessary, then it was up to the people to decide the constitutional changes that would result. In other words, Cambacérès established the principle of a plebiscite. It remained to be decided what question would be asked. A few hours later, everything had been arranged and two questions formulated: ‘Should Napoleon Bonaparte be made Consul for Life?’ (it was the first time his Christian name had appeared in public), and ‘Should he have the right to designate his successor?’ When Cambacérès asked if anyone had anything to add, no one responded. It was then put to the vote. Five members of the Council abstained, but most voted for it, though with little joy or enthusiasm.

13

Dedicated republicans were beginning to be worried, but not enough to do anything. Théophile Berlier, for example, a republican and a member of the Council of State, pointed out that ‘It was difficult for me not to see retrograde tendencies [in all this], which grieved me all the more since I was sincerely attached to the First Consul.’ Berlier was still convinced, as no doubt were many others, that Bonaparte was the man sent by providence to consolidate ‘our republican institutions and to make them respected by all of Europe’.

14

The word ‘Republic’ still remained, and that seems to have been enough to placate those who may have had reservations about Bonaparte’s intentions. But just as importantly, for men like Berlier, Boulay de la Meurthe, Thibaudeau and others, Bonaparte was the best guarantee of the Revolution. The refrain – ‘The men of the Revolution have nothing to fear; I am their best guarantee’ – was constantly repeated both by Bonaparte and by his supporters.

15

This was in essence another successful parliamentary coup. Bonaparte was supposed to have been kept in the dark, and he even left the room in which they deliberated the plebiscite on 10 May, but that was nothing more than pretence. Nevertheless, even for him this was moving faster than he thought prudent. He rejected the second question relating to heredity, although Cambacérès attempted to persuade him to keep it.

16

Not that Bonaparte wanted the power to name a successor; as he intimated to Cambacérès, informing the public of his successor was next to worthless. Rather he was playing a game of moderation. Now that the Council of State, the rival institution of the Senate, had offered him more than he had ostensibly desired, he appeared more modest by rejecting part of their offer.

17

Moreover, he thought it would no doubt engender a debate that he preferred to avoid at this stage, fearful that his opponents could rally round the question. Who could oppose, on the other hand, the indefinite prolongation of his powers?

One senator, Jean-Denis Lanjuinais, is reported to have said, ‘They want us to give France a Master. What is to be done? Any resistance from now on would be pointless, whole armies would be needed to oppose it. The only thing to be done is to keep quiet; it is the course of action I have taken.’

18

In fact, the Senate was not as meek as has been made out. Under the circumstances, it did the only thing it could do: it prevaricated by naming a commission to consider the question. The commission eventually handed down a finding that stated, ‘there is, at present, no action to be taken in relation to the messages in question’. This was a reference to the notes sent by Bonaparte and the two consuls informing the Senate that they would be consulting with the people. In other words, impotent before the turn of events, the Senate nevertheless found a way to reject the call for a plebiscite.

19

It was not much of an act of defiance. On 11 May, the members of the Senate, along with those belonging to the Tribunate and the Legislative Corps, went to the Tuileries to congratulate the First Consul. The deputies handed Bonaparte their independence on a silver platter.

The Imagination of the French People

So another plebiscite was prepared, paying lip-service to the revolutionary notion of the sovereignty of the people. The plebiscite of 1802, however, was concerned with Bonaparte’s powers and title. As with the plebiscite of 1800, registers were opened at the communal level. Voters were meant to pronounce publicly in writing whether they were for or against the life consulship (the other two consuls were implicitly included in the plebiscite). The groundwork was laid by the regime through the media of the day,

20

by the local administration and also this time by the Church; it could hardly refuse anything to a man who had just given its members the freedom to practise. The Bishop of Metz, for example, came out officially for a ‘yes’ vote.

21

Unlike the plebiscite of 1800, the results of 1802 did not need to be inflated. About 3.6 million ‘yes’ votes were recorded, a reflection of the general acceptance of Bonaparte as head of state as well as of the Consular regime that had brought stability to France’s political landscape. In fact, the number of real ‘yes’ votes had doubled since 1800. These figures mean two things: that only two out of five Frenchmen eligible to vote had done so, a proportion which nevertheless represents the summit of popular adherence to the man and his system; and that, despite the acceptance of Bonaparte, the regime could not capitalize on it in the way it had done in 1800 when the results were falsified.

22

Once again, the ‘no’ vote was negligible, although many of the negative votes came from the army, disappointed republicans who did not wish for a life Consulate; the strongest opposition came from the Army of the West, commanded by General Bernadotte, and from the Army of Italy.

23

That some within the army were displeased by the idea of a Consulate for life may have had nothing to do with Bonaparte – there is some indication that discontent over lack of pay motivated some to vote ‘no’ – but most would have voted ‘no’ on ideological grounds.

24

The results of the plebiscite were announced around two in the afternoon on 3 August. The Senate arrived at the Tuileries in grand costume accompanied by a cavalry escort. Bonaparte was in the middle of an audience with foreign ambassadors; it was suspended. The new president of the Senate, François Barthélemy, addressed the First Consul in terms that made it seem the Senate were in perfect accord with the will of the people. Indeed, the phrase pronounced was ‘The French people names and the Senate proclaims Napoleon Bonaparte, First Consul for Life.’

25

In a break with tradition, both monarchical and revolutionary, and in spite of Bonaparte’s refusal of the offer, he was granted the power to name his successor, a right that not even the kings of France had enjoyed. For the senators, it was a humiliating position to be in. They had opposed the Consulate for life and were in effect now consecrating their own downfall in front of the representatives of the monarchs of Europe. Bonaparte replied in a set speech that was, according to an Irish witness, concealed in the crown of his hat.

26