Citizen Emperor (42 page)

Authors: Philip Dwyer

Napoleon too was looking for support on the Continent, and he was helped by the fact that Britain was not exactly popular in many European courts.

33

He had already secured French influence in southern Germany by concluding treaties with Bavaria, Baden and Württemberg (although the latter two only after the war had begun).

34

His objective was to make sure that his rear was safe while he attacked Britain, but he also had thereby a passage through to Austria if the occasion arose. The southern German powers, combined with Holland, Spain and northern Italy, meant that Napoleon proved better at forming an effective coalition than the allies, not because their combined power was stronger but because the southern German states gave him an easy and secure route into the heart of Austria.

35

Or so goes the argument. As we shall see, southern Germany, as it had so many times before, became the battleground over which the war was fought. For the moment, Napoleon’s diplomatic efforts were combined with a public relations exercise. As in 1800, he wrote to the various kings of Europe in an apparent attempt to find a peaceful solution to the problem, but, as in 1800, these initiatives cannot be taken too seriously.

36

The journey on the road to Austerlitz had begun.

The Army of England

The threat of invasion provoked nightmares among the people of England.

37

The French camp at Boulogne could be seen ‘quite distinctly’ from some parts of the English coast. In France, however, Napoleon used the war with England to unify the nation around his person, possibly to greater effect than the coronation. There was no real enthusiasm for the war despite the long-held hatred of the French for the English; the French people needed convincing both that it was the right thing to do and that an invasion of England was in the realms of the possible.

38

That is why the planned invasion was the object of a propaganda campaign. Several songs for the invasion were ordered, as were several comic plays.

39

A series of medallions representing those who had successfully invaded England – Caesar, Septimius Severus, William the Conqueror, Henry VII – was struck.

40

A statue of William the Conqueror and a square named after him were considered for Saint-Germain near Paris.

41

At the camp at Boulogne, a number of ancient Roman arms were coincidentally uncovered, as well as coins of William the Conqueror, precisely where Bonaparte’s tent was pitched.

42

It was an omen of things to come. Just as Charlemagne had been disinterred and used by the regime, so too was William the Conqueror, not to justify the impending invasion of England but to demonstrate that there was a historical precedent and that therefore an invasion was possible. At one stage, Vivant Denon even came up with the hare-brained idea of burying a statue of William the Conqueror in the Seine and then uncovering it as if by chance; the statue was then to be hauled upriver to Paris in a barge, once again as an omen of the impending invasion of England.

43

Fortunately, Bonaparte did not buy into the scheme. On the other hand, the Bayeux tapestry was brought from Calvados to Paris and exhibited at the Louvre at the beginning of 1803, announcing the French victory that was about to take place;

44

hundreds of copies of the exhibition catalogue were distributed to the army. Whether any of this had an impact on public opinion is doubtful. On 23 September 1805, Napoleon appeared before the Senate and gave a speech explaining that he was about to leave the capital and rejoin the army at Boulogne.

45

As he left the Senate, driving through Paris to Saint-Cloud, he noticed that the mood of the crowds had ‘cooled, and he was greeted with less alacrity than usual’.

46

Their reaction hurt him, but then crowds rarely, if ever, cheer the outbreak of war.

One determining factor would have allowed Napoleon to invade England: he had to control the Channel for several days while the French flotilla sailed across in convoys of 200 boats.

47

His plan was somehow to convince the British that he was going to cross the Channel without the protection of the French fleet. He succeeded to such an extent that many diplomats of the time, some military figures such as the Archduke Charles and even members of the British government and senior officers in the Royal Navy were persuaded that the whole idea of an invasion was a confidence trick. In the meantime, Napoleon was trying to combine the scattered French navy and manoeuvre them away from Europe, in the hope that the British fleet would give chase. The French could then turn around and unite in the Channel long enough to give them naval superiority.

48

Given the size of the fleet that was assembled (more than forty ships of the line, twenty frigates, fourteen corvettes and twenty-five brigs, more if the Spanish fleet is taken into account), as well as the thousands of landing craft that were purpose built, and the millions of francs that were spent in preparations, it is clear that Napoleon was serious about an invasion of England. Any suggestion that he was not, that he was putting on a show of force in the hope of obliging London to negotiate, or indeed that the camp at Boulogne was a front to ‘facilitate the assembling of troops for a Continental war’, can be discounted.

49

Speculation about Napoleon’s intentions existed at the time. The Prussian ambassador reported back to Berlin in May 1804 that Bonaparte’s ‘secret wish’ was for war on the Continent.

50

Doubts about Napoleon’s real plans were further inflamed by an alleged admission to Metternich in 1810 that he never meant to invade England and that the army gathered at Boulogne was ‘always an army against Austria’.

51

This is, however, little more than an indication of Napoleon’s inability to admit defeat – in this case, the aborted invasion – and his tendency to rewrite the past to conform to his idealized views of it. At the time, he was so confident that the invasion would be successful that dies were prepared for a commemorative medal to celebrate the victory. On one side is a profile of Napoleon crowned with laurels, and on the other an image of Hercules strangling Antaeus.

52

Beneath is the optimistic inscription ‘Struck in London, 1804’. All the evidence suggests, therefore, that Napoleon planned to invade England, but that he also realized there was a possibility of war with the Eastern powers, rumours of which abounded in the summer of 1804.

53

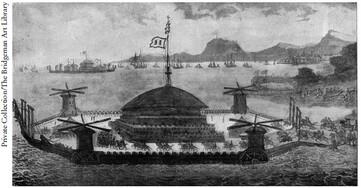

John Fairburn,

A View of the French raft, as seen afloat at St. Maloes in February 1798

, 13 February 1798. Rumours of an impending invasion inspired English caricaturists to imagine the most outlandish plans to cross the Channel. This print shows a raft, 180 metres long, bristling with 500 cannon, capable of transporting 15,000 troops. Others showed floating fortresses that would transport men and materiel by balloon, and even a cross-Channel tunnel. There was talk of steamboats, submarines, torpedoes and blockading British ports with mines, all aspects of modern naval warfare which, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, were far from practical.

54

Bonaparte’s initial orders were for landing craft to be ready by December 1803, only six months after the formation of the army, but the timeframe was unrealistic and over the coming months the number and type of craft ordered were to change dramatically.

55

The projected invasion of England, ambitious in its breadth and scope, was certainly much better planned and prepared than the expedition to Egypt.

56

Nevertheless, despite the enormous effort put into its organization, any chance of success depended on luck. In one exercise conducted in July 1805, Marshal Ney’s entire corps, including horses and equipment, were embarked on barges at Etaples (twenty-five kilometres south of Boulogne) in forty-nine minutes.

57

However, an exercise held in bad weather on 20 July 1804 at Napoleon’s insistence demonstrated just how unsuitable the flat-bottomed boats were for the rough Channel seas. To his credit, Admiral Bruix, in command of the flotilla at Boulogne, refused to obey the order to put to sea; it was clear to all that a storm was brewing. Bruix and Napoleon almost came to blows over the matter, Napoleon threatening to strike the admiral with his riding crop, Bruix placing his hand on the hilt of his sword as those in the Emperor’s entourage stood around dumbfounded. Napoleon got his way, as a result of which twelve boats and barges sank with the loss of between 200 and 400 men.

58

At one stage, Napoleon got into a boat and ordered the crew to row him out to help others, but to little effect. In a letter to Josephine the following day, he referred to the incident in romantic terms. ‘The soul was between eternity, the ocean and the night.’ He went to bed at five in the morning with the impression that he had lived through some sort of ‘romantic or epic dream’.

59

The Royal Navy did not stand idly by and watch the French amass an invasion fleet. They attacked and harassed whenever and wherever they could, in spite of the coastal defences erected to protect the fleet. In 1804, the Royal Navy lost twenty-one ships blockading the French ports.

60

Every now and then they would bombard one of the ports in lightning raids that could sometimes have devastating effects. On other occasions, these attacks were easily beaten off. Many believed as a result of the British efforts that an invasion was impossible, but Napoleon insisted preparations go ahead.

The Battle of Cadiz

The minister of the navy, Rear-Admiral Denis Decrès, was an experienced sailor who had engaged the British in a number of different theatres, but he was no match for Napoleon, who attempted to control the everyday workings of the navy during this period. Besides, Decrès was far from convinced of the potential success of an invasion. His lack of faith in the ability of his own fleet was a continual drawback.

61

Letter after letter addressed to Napoleon rated as negligible the chances of gaining the necessary naval superiority in the Channel.

62

There was a momentary setback when Vice-Admiral Latouche-Tréville, in command of the Mediterranean fleet at Toulon and whom many considered to be the best naval officer in France, died suddenly in August 1804, after an illness he had contracted while at Saint-Domingue.

63

As a consequence, plans for the invasion were more or less put on hold; Napoleon even temporarily gave up the idea, at least for the immediate future.

64

However, alternative plans had been developed by the spring of 1805.

65

A replacement was found in the person of Vice-Admiral Pierre-Charles Villeneuve, but he was not Latouche-Tréville. On the contrary, Villeneuve appears to have been traumatized by his experience during the battle of the Nile, which saw Nelson obliterate the French fleet off Aboukir. Villeneuve escaped that battle with his life, but developed as a consequence a morbid dread of Nelson. He was not, therefore, the kind of commander who could lead by daring example.

66

He at first refused the command, but was persuaded against his better judgement to accept. At the end of September 1804, he was briefed on a new strategy in which the invasion of England was only one part of a much larger plan to attack Britain in the rest of the world, including Africa, South America, the Caribbean and Ireland.

67

In the event, the strategy was never put into effect, but it provides us with an insight into Napoleon’s mind-set, the extent of his ambition and his determination to strike at England wherever he could. A definitive invasion plan was not decided on until the middle of April 1805. It was the seventh and probably least nonsensical in a line of impracticable plans. Before that, Napoleon had constantly changed his mind about what he wanted and what he expected from his subordinates. Even once the definitive plan had been adopted, he had no realistic conception of the limits and possibilities of naval warfare, and did not take into account the fact that the French vessels were manned by inexperienced sailors.