Citizen Emperor (39 page)

Authors: Philip Dwyer

Baron Francois Gerard,

Napoléon Ier en costume du sacre

(Napoleon I in his imperial robes), 1806. Napoleon is wearing the coronation garments: the embroidered white silk tunic; the white gloves, also embroidered; and the mantle of purple velvet lined with ermine. On his head is a golden laurel wreath. In his right hand, which is wearing the emerald ring, he is carrying the sceptre. On the cushion on the stool to his right is the hand of justice and the globe. These last two were destroyed during the Restoration.

The painting was purchased by the Legislative Corps, despite an unfavourable secret report to the minister of the interior by Jean-François-Léonor Mérimée, an adjunct secretary at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts, who visited Ingres’ studio at the end of August, a couple of weeks before the opening of the 1806 Salon.

80

Mérimée’s impressions of the painting – he described it as ‘Gothic’ and ‘barbarous’ – corresponded completely with the almost universal adverse public reaction that was to follow.

81

Even a fellow artist, François Gérard, invited to Ingres’ studio, was supposedly shocked by what he saw.

82

The portrait had a negative effect on just about everyone who saw it (including Ingres’ teacher David, who found the painting incomprehensible),

83

both art critics and the crowds that streamed past to view it during the Salon. A play on words with the artist’s name dubbed the painting

mal-Ingres

(sickly), no doubt repeated from the types of quips that could be found in the pamphlets of the time:

Vous avez fait votre empereur mal, Ingres

(You have made your Emperor sickly, Ingres), or again,

Vous avez fait mal Ingres, le portrait de Sa Majesté

(Ingres, you have badly made the portrait of His Majesty).

84

Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres,

Napoléon Ier sur le trône impérial ou Sa Majesté l’Empereur des Français sur son trône

(Napoleon I on the imperial throne), 1806.

One critic suggested that Ingres had single-handedly retrogressed art four centuries since it was nothing less than gothic, a term that had not often been used till then.

85

The criticisms were aesthetic, but also in part political.

86

A former Jacobin by the name of Chaussard who had, like many other Jacobins, accepted Napoleon largely because he had portrayed himself as a simple man of the people, objected to Ingres’ work precisely because it was too lavish, too elaborate and too retrograde. It somehow did not sit well with the image of the young, victorious and largely republican military hero that Bonaparte had cultivated in the past. Royalist critics, on the other hand, were not impressed by this blatant attempt to legitimize the Empire through a return to monarchical symbols.

87

Criticism came not only from those hostile to the regime but from those, on the contrary, who supported it, outraged that Ingres seemed to herald a return to Bourbon traditions. The painting somehow took away the heroic from Napoleon’s character.

88

Ingres was hurt by the reaction. He had had every reason to believe that his painting would be a success.

The Distribution of the Eagles

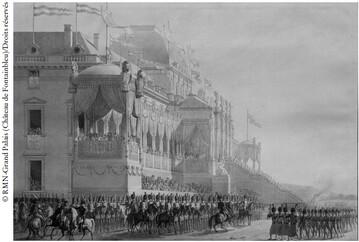

Three days after the coronation, the Distribution of the Eagles took place on the Champ de Mars in front of the Ecole Militaire where Napoleon graduated in 1785. At eleven o’clock in the morning, the imperial couple and their respective households, accompanied by detachments of chasseurs, Mamelukes, grenadiers and gendarmes, proceeded to the Ecole Militaire, which had been transformed for the occasion by Percier and Fontaine into a covered gallery which one approached by climbing forty steps. The event was in some respects a tribute to the importance of the army in the new imperial regime.

89

The entire edifice was covered in velvet.

Regimental commanders from both the regular army and the National Guard, in the pouring rain – Fontaine speaks of ‘the most disastrous day of the whole winter’

90

– with few or no spectators, took an oath of loyalty to the Emperor to defend their standards to the death. Josephine and most of the court ladies retired to warmer spots. Only Caroline remained with her brother and followed the ceremony to the end. ‘Soldiers,’ Napoleon shouted, ‘here are your standards, these eagles will always be your rallying point; they will go everywhere the Emperor deems it necessary for the defence of his throne and his people. Do you swear to sacrifice your lives in their defence and to maintain them constantly on the road to victory? Do you swear it?’ Those present are supposed to have shouted out as one voice, ‘We swear it.’ Several salvoes of artillery were then fired, and the troops marched past.

Jean-Baptiste Isabey, from

Le livre du sacre

. The

Livre du sacre

was a sort of official record book of designs and prints of highlights of both the coronation and the ceremonies that followed, as well as the uniforms worn. Although begun in 1804, it was not completed and published until 1815, during the Hundred Days.

91

Here we see the facade of the Ecole Militaire, looking on to the Champ de Mars, redecorated for the occasion.

This was the first time that troops had been obliged to swear an oath to defend their eagles, which were in deliberate imitation of the standards employed by Roman legions, and which had replaced the flags and standards used during the revolutionary wars.

92

The eagles, made of wood and gold and mounted on poles, became associated with the Empire. Just as importantly, the troops were also given the tricolour, thus marrying two symbols, one representing the Empire, the other the Republic. Though the ceremony did not make that much of an impression on those gathered, we know how highly prized the eagles became in the regiments. Any number of accounts of the extremes to which soldiers went to protect them in the course of battle are testimony to the value placed on them by the men assigned to protect them.

93

A great deal of splendour was on display in these ceremonies to encourage the bonding of the officers of the army to its commander-in-chief. In later years, the ceremony for newly promoted officers would take place in the Salle du Trône at the Tuileries (when Napoleon was in Paris), while Hugues-Bernard Maret, director of Napoleon’s cabinet, read out the oath.

94

Napoleon had done this kind of thing before, but on a smaller scale, almost as dress rehearsals for what took place on the Champ de Mars. During the festivals of 14 July, in 1797, 1801 and again in 1802, for example, he had distributed flags to different units and had them swear an oath: ‘You will always need to rally to this flag; swear that it will never fall into the hands of the enemies of the republic, and that you will all perish, if necessary, to defend it.’

95

On this occasion, the ceremony was over in a very short time, and the whole thing ended in utter confusion. Soldiers milled about in the middle of the plain, which had turned to mud, their uniforms soaked through, their hats deformed by the rain, all of them freezing cold and none of them sure what to do next.

96

The only incident of any note was the appearance of a young man who approached the steps to the throne shouting, ‘No Emperor! Liberty or death!’ He was immediately arrested. A medical student by the name of Faure, he was incarcerated in Charenton, a hospital for the insane, where he was to stay until he was ‘cured’.

Jacques-Louis David,

Serment de l’armée fait à l’Empereur après la distribution des Aigles au Champ de Mars

(Oath of the army made to the Emperor after the Distribution of the Eagles on the Champ de Mars), 1810. Napoleonic theatre at its best, even though it reaches absurd proportions. Note the general in the front of the group, inspired by Giovanni da Bologna’s figure of

Mercury

, standing on tiptoe on one leg. The viewer is floating in mid-air so to speak, at the top of the extraordinary, temporary flight of stairs constructed for the occasion by Percier and Fontaine, all the better to see the action and read the banners.

97

David’s painting of the

Distribution des Aigles

, a kind of Napoleonic version of his

Serment des Horaces

(Oath of the Horatii), was not completed until 1810. The artist had to overcome a number of difficulties, including the fact that Josephine was no longer Napoleon’s wife, so she, along with her ladies-in-waiting, had to be painted out of the original picture.

98

We are used to that kind of thing happening in modern dictatorships, but this is the first time that history had been deliberately altered by a modern European head of state. One can see where Josephine should have been; the space is emphasized by Eugène de Beauharnais’ out-thrust leg. One art historian has suggested a subversive element to the painting: Napoleon is lost in the crowd of courtiers, confronting an unruly army over which he has no control.

99

It is a sign that, by the time the painting was completed, people had tired of the man and his regime, perhaps no better illustrated than by a detail, another subversive element, in the painting that is generally overlooked.

100

In the bottom right-hand corner a soldier, with his back to the onlooker, is walking away with a folded flag marked ‘La République’.