Citizen Emperor (35 page)

Authors: Philip Dwyer

The choice of Notre Dame for the ceremony is itself an interesting one. Napoleon at first proposed that the coronation should not take place in Paris, which obliged the councillors of state to debate alternatives, each one eliminated in turn so that Paris soon became the obvious choice.

131

Rheims, the cathedral where every French king except two (Louis VI and Henry IV) had been crowned, was for that reason eliminated: it was too closely associated with the former monarchy. Aachen, where not only Charlemagne but thirty-four other emperors and ten empresses had been crowned, was ruled out by the pope on the grounds that he did not want to visit the region because it contained too many Lutherans.

132

The clergy of Orleans proposed that city’s cathedral, but the offer does not appear to have been seriously considered.

That left Paris, but Napoleon nevertheless hesitated. Since the Moreau affair, public approval of the regime had been tepid, and the capital remained a hotbed of republicanism.

133

In June, Napoleon suggested that the Champ de Mars would be an appropriate place for a coronation, and at first the members of the Council of State agreed.

134

He revisited the question a couple of weeks later, having had second thoughts in the meantime. He had decided that the people were to be excluded from the event. If an altar was placed in the middle of the Champ de Mars, he declared, it would become a populist ceremony. It was important that Paris should not think of itself as the nation. This was no longer the Revolution, when the people of Paris had intervened directly in the political process.

135

Besides, there was always the risk of bad weather; it would not look dignified if the imperial family were exposed to the rain and the mud, as had been the case during the Festival of the Federation in 1790.

136

The Church of Saint-Louis at the Invalides was considered as an alternative location – it had been the site of a number of civil and military ceremonies during the Revolution and the Consulate – but Fontanes thought the church inadequate for such a grand occasion and recommended instead Notre Dame.

137

Napoleon agreed. Notre Dame had undergone a number of transformations during the Revolution, from a cathedral to a Temple of Reason, to a Temple of the Supreme Being, to the principal church of the Theophilanthropists, before finally reverting to the Catholic faith in April 1802. It was transformed once again for the coronation. The gothic interior of Notre Dame was hidden behind decorations of red and blue silk designed by Charles Percier and François-Léonard Fontaine, who thereby converted it into a vast theatre, a neo-Greek temple. Buildings around the cathedral were demolished to make room – the space in front of the building was cleared, resulting in the square that we see today – while triumphal arches along the route leading to the cathedral were erected.

A member of the Council of State, Portalis, suggested the idea of having the pope confer on Napoleon a blessing that would transform the Empire into a Christian monarchy, and Napoleon into a legitimate monarch.

138

Bringing the pope to Paris, however, was no easy thing. In the past, the pope had travelled to crown the king of France on only two occasions: when Stephen II (III) crowned Pepin (the Short) King of the Franks in 754; and when Stephen IV (V) crowned Louis the Pious emperor in 816 at Rheims, almost a thousand years before. All other kings and emperors anointed by the pontiff had gone to Rome, including Charlemagne. Napoleon, however, wanted the pope to come to him, thereby asserting the power of the French Church,

139

and the power of the Emperor over the pope. The presence of the pope, moreover, would help cut the religious base from under the counter-revolution, and bring about the national reconciliation Napoleon was aiming at. This is not to say that there was no opposition to the pope’s presence, but Napoleon’s wishes prevailed. It was in that respect an attempt to recreate, at least on the surface, the coalition between throne and altar that had existed before the Revolution, as well as challenging Francis as Holy Roman Emperor for the domination of Germany.

140

Negotiations with the Vatican began in May, very tentatively at first.

141

Napoleon told the papal legate in Paris, Cardinal Caprara, of his wish to be consecrated by the pope, but added that he did not yet want to make a formal request for fear of its being rejected.

142

The pope at first baulked, arguing that there would have to be a serious religious motive for him to leave Rome. The Curia pointed to the illegitimacy of the monarch, the pope’s poor health, the fear that he would not be respected in revolutionary France, and the policy of freedom of religion practised under Napoleon. If the negotiations took several months to conclude, it was because Rome had every advantage in drawing things out: it would leave a better impression with the courts of Europe (a too hasty agreement would look bad); and it hoped to receive from Napoleon as many changes in its favour as possible (the pope was looking to alter the situation that had developed ever since Napoleon imposed the Organic Articles on the Church). Eventually, however, the pope had to concede on almost every point, but the process was exhausting and made him very anxious and in the end quite sick.

143

Accompanied by an imposing entourage of ecclesiastics and servants – 108 people divided into four convoys, though it was not as imposing as Napoleon had hoped – the pope did not leave Rome until 2 November. Fêted along the route in Italy, he took at least two weeks to reach Paris. At Lyons (19 November), in spite of torrential rain, 80,000 people turned out to see him.

144

Napoleon sent his uncle, Cardinal Fesch, to hurry things along, while Cardinal Cambacérès, Archbishop of Rouen and the arch-chancellor’s brother, was also sent to greet the convoy.

145

The date of the coronation kept having to be put back – from 9 to 25, to 26, then to 29 November and finally to 2 December. The pope would have preferred Christmas Day, the day on which Charlemagne had been crowned in 800, and was no doubt dallying in order to get his way.

When the pope’s convoy reached the forest of Fontainebleau on 25 November, Napoleon met him according to a prearranged plan, as though he had come across the pontiff by chance while out hunting, to avoid having to genuflect before him.

146

Then, in what has to be one of the strangest meetings of any two heads of state before or since, he waited until the pope had got out of his carriage before he dismounted and went to meet him on foot. Before they could get too close, however, the imperial carriage came between them: Napoleon got in on the right side (the place of honour), while the pope got in on the left. They then drove to Fontainebleau together, accompanied by a fittingly pagan escort of Mamelukes. The Château de Fontainebleau, which had not been used since the beginning of the Revolution, had been prepared to receive both entourages. Forty apartments, 200 lesser lodgings and stables for 400 horses had to be made ready. Preparations were still not quite complete when the pope arrived. He was left standing at the top of the main staircase where Napoleon had accompanied him. A quip about the event was soon circulating in Paris –

Le Pape Pie sans lit

(Pope Pius without a bed).

147

This first encounter was to decide the etiquette for the remainder of the pontiff’s visit. Napoleon and the pope entered the city at around 7.30 on a dark winter’s evening. It is impossible to know how to read this, and whether Napoleon wanted the pope’s arrival in Paris to go unnoticed. Word got out, though, and a large crowd gathered at the Barrière d’Italie, in spite of the cold and the darkness, to await the arrival of His Holiness. As soon as the carriages appeared, cries of ‘Long live the Emperor!’ and ‘Long live His Holiness!’ rang out.

148

It was only the next day that the rest of Paris, assisted by a pealing of church bells, found out that the pope was at the Tuileries. Crowds of people flocked to the palace where they would call out for him to appear, and would then kneel to receive his blessings. In the course of 29 November, he did so twenty times.

149

Indeed, he was becoming so popular that, according to some, Napoleon was starting to get jealous.

150

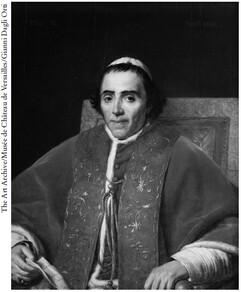

Jacques-Louis David,

Portrait du Pape Pius VII

(Pope Pius VII), 1805. Pius VII was sixtytwo years of age, and was according to contemporaries a ‘good man’, diffident, without ambition, but sharp and subtle. The modesty of his appearance and something of that goodness seems to come through the canvas of David’s portrait. One of the reasons he agreed to come to Paris was his belief that he could influence Napoleon and even bring him around to his way of thinking –to convert him, so to speak.

From the moment of Pius VII’s arrival, it was obvious that Napoleon intended to make the pontiff subordinate to him. Everything was organized in such a way that the spiritual power of the Church was subjected to the temporal power of the French state.

151

Pius was, for example, obliged to walk and sit on Napoleon’s left (rather than on his right), he was obliged to wait for an hour and a half in Notre Dame on the day of the coronation before Napoleon arrived,

152

and was, if eyewitness reports are anything to go by, entirely dominated by Napoleon’s personality. The pope, on the other hand, felt ‘a mixture of admiration and fear, of paternal tenderness and pious gratitude’ towards Napoleon.

153

A Vexed Question

Then Josephine dropped a bombshell. Every member of the Bonaparte family hated Josephine, and continually intrigued to diminish her influence.

154

Conscious of her precarious position, and in an attempt to shore it up, she took the initiative and asked for a secret audience with the pope to reveal that she and Napoleon had not been married in a religious ceremony. The pope refused to carry out the coronation unless the union was immediately consecrated. Josephine had not informed Napoleon of her intentions. It was an astute move on her part; a religious ceremony made divorce not impossible but at least more difficult.

155

Napoleon had been outmanoeuvred. The coronation was worth a mass. At around four in the afternoon on the eve of the coronation, Cardinal Fesch conducted the wedding ceremony, assisted by the curé of Saint-Germain l’Auxerrois.

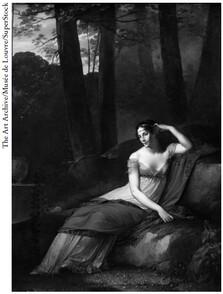

Detail of Pierre Paul Prud’hon,

Portrait de Joséphine de Beauharnais

(The Empress Josephine), 1805. Josephine, portrayed here in dress typical of the era, was said to have had a significant influence on feminine fashion. A few weeks before the coronation, one of her ladies-in-waiting, Elisabeth de Vaudey, described her as pretty and witty. There had, however, been talk of Napoleon’s divorcing Josephine and marrying a princess from the Margrave of Baden.