Citizen Emperor (32 page)

Authors: Philip Dwyer

Here too we find material that rejects the Revolution as a democratic experiment and supports, if not the idea of monarchy, then at least the notion of a strong executive centred on one man. ‘Fourteen centuries of monarchy,’ declares a pamphlet by General Jean Sarrazin, ‘even if often feebly administered, speak more eloquently in favour of the throne than fourteen years of misfortune and setbacks for the republican state.’

38

General Henry, writing from Nantes, argued that he was ‘convinced by experience that under the Republic, the supreme power remained too long divided between the hands of many’, which had resulted in constant anarchy and disorder, and that the centralization of power was best suited to empire.

39

The desire to see order restored was a constant; a surrogate to the tribunal of first instance at Versailles wrote that even if the Consulate was able to ‘dissipate the deep darkness of night’ certain souls remained troubled. ‘It is time’, he continued, ‘to revive the social order, [and it is time] that sovereign power is reunited in the hands of one man.’

40

There is, moreover, a prevailing sentiment among many of these letters that Napoleon deserved the throne through his actions.

41

There are so many letters – one of them includes a helpful remedy against poison

42

– that it seems the movement towards empire revived monarchical tendencies that had lain dormant during the Republic. The sentiments expressed often fall within the logic of what might be called a monarchical reflex – that is, a resurgence of belief in the sacred nature of the monarchy, and not just any monarchy, but one founded in the person of Napoleon.

43

This is not the same, however, as the notion of sacrality that existed in

ancien régime

France; it had now taken on a new form, founded on notions of individual destiny (Napoleon’s), as well as on the sovereignty of the people. Hence the constant references to ‘providence’ or the ‘hand of God’ having placed Napoleon on the throne or of having saved him from assassination attempts so that he could continue his work,

44

or to the title ‘emperor’ as a reward for his services to the state (often with the assertion that he had saved France from ruin),

45

or to the idea that France could be saved from domestic and foreign enemies only when hereditary power resided in one family.

46

There are, moreover, references to Napoleon as father of the people,

47

remarkably similar to the kinds of patriarchal discourse found prior to 1789. Consequently, one cannot but conclude that the letters embodied a set of beliefs and values that were profoundly rooted in the cultural practices of the day, notwithstanding the creation of a republic and the execution of the king in 1792.

48

The person of Napoleon came to symbolize all that French politics and society had been striving for since 1789 – the embodiment of the ideals of the Revolution, as well as the principle of constitutional monarchy.

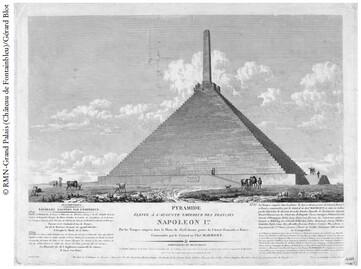

Anonymous,

Pyramide élevé à l’Auguste empereur des Français, Napoléon 1er

(Pyramid erected to the August Emperor of the French, Napoleon I), no date. On his own initiative, General Marmont built this imposing pyramid in the space of a month at the Camp of Utrecht. Forty-five metres tall, it was surmounted by an eighteen-metre obelisk.

49

Today dubbed the Pyramid of Austerlitz, it can still be seen outside the city of Utrecht in Holland. Each face was marked with an inscription, one of which contained the declaration that the pyramid was built as a testimony to the army’s ‘admiration and love’ for Napoleon.

In spite of this public outpouring, support for the Empire was by no means unanimous. There was never a concerted intellectual or political opposition to it, but resistance to it can be found throughout its existence.

50

Most of it came either from republican elements in the military,

51

from former Jacobins or from royalists. General Verdier, for example, a friend of the defunct General Kléber, was at Leghorn when news of the proclamation reached the army through the

Moniteur

. He was so angry that he tore up the newspaper in front of several other officers (he was denounced and disgraced for three years).

52

At Toulon, opinions were divided; pamphlets and caricatures were being circulated against Napoleon. At Clermont-Ferrand, he was publicly insulted, enough for the police to take note.

53

At Nîmes, during the night of 7–8 August, a group of opponents calling themselves the ‘Implacables’ posted insults against Napoleon in the public squares of the town.

54

At the camp of Bolougne, where the gathered army was predominantly republican, the proclamation of the Empire represented for many a return to old monarchical structures. Despite this, few officers refused to sign the petitions in favour of empire and some that did refuse were relieved of their commands.

55

Even some who admired Napoleon were a little worried about the extent of his ambition. ‘He only wanted supreme power’, wrote one officer, ‘to break all the chains that, as First Consul, he still encountered . . . Why did we have a bloody revolution to return [to the monarchy] so quickly?’

56

Plebiscitary Leadership

The matter of heredity was taken to the people of France. Another plebiscite was held, this time during the month of June 1804. There was no mention of the imperial title, and the people were not asked to approve or disapprove of the Empire. They were simply asked to ratify what had already taken place.

The official results, revealed in August, were almost the same as those of the plebiscite of 1802 – over 3.5 million had voted ‘yes’ and only 2,569 had voted ‘no’ – but in reality the overall turnout had fallen, in some regions dramatically, so that there were 300,000 fewer votes than in 1802.

57

One has to take into account that by this stage France was actually larger than it had been in 1802 – several new departments had been added – and that the results for the army and navy were grossly exaggerated.

58

In some departments, the local prefects simply doubled the number of ‘yes’ votes received from their subordinates, and at the same time slightly reduced the number of negative votes.

59

This kind of fraud appears to have been common. It tells us at the very least that some local administrators were keen to produce strong positive returns so that their administration looked well in Paris. Corruption was built into the imperial system at the lowest levels, and was indicative of a hierarchy dependent on the approval of one man.

About 35 per cent of the electorate turned out to vote (the regime boasted that it was 40 per cent), which in itself was a better turnout than previous elections and plebiscites had achieved. It is also interesting to note that while some departments returned a higher ‘yes’ vote, many more – including Brittany, the east, the centre, the south-west and Languedoc – returned a much lower ‘yes’ vote than in 1802, sometimes up to 40 and even 50 per cent lower. This has been interpreted to mean that popular support for Napoleon was starting to wane,

60

but it is more likely there were real concerns about the nature of a hereditary regime and about the future of the representative system. ‘I would vote affirmatively’, wrote one voter in the Aube, ‘if the history of all peoples did not teach me that the granting of supreme power for life, even in the hands of the most honest man, has very often changed the attitude of the individual in question. Such an accretion of power has frequently been dangerous for public and personal liberties.’

61

Nevertheless, the vote was still a resounding vote of confidence in the person of Napoleon.

62

Given the figures and in the face of a reasonably high turnout, it would appear that his policy of national reconciliation was finally starting to bear fruit. But the real victory came from the manner in which the plebiscite was used by the regime to promote Napoleon as someone who had been called to the throne by the people of France, and that it was his personal merits that had led him there.

Trinkets and Baubles

In the six months between the declaration of the Empire in May and the coronation ceremony in December, an entirely new, original iconography had to be invented. Just as former and indeed future monarchs created symbols to assert and strengthen a claim to the throne, so too did Napoleon and his entourage have to devise symbols that had their roots in both the Roman and Carolingian Empires, as well as reconnecting with French national history.

63

Napoleon appears to have temporized. Prior to the Revolution, enormous importance had been placed in the body of the king as representative of the monarchy. After the execution of Louis XVI in 1792, the sacred character of the king’s body had been defiled, so to speak, and it would have been difficult to turn back the clock. As a consequence, the importance of kingship began to be displaced on to the trappings of rule, in this case on to the new symbols and insignia that were created to represent Napoleon’s new status as emperor.

64

One of the most important decisions concerned the icons that would represent the new dynasty, for that was in effect what Napoleon was founding. The architects Charles Percier and Pierre-François-Léonard Fontaine suggested a lion resting its paw on a glaive or spear.

65

After discussing a number of possibilities – the eagle, the owl, the elephant (very fashionable at the time), the lion, the cock and even the fleur de lys – Napoleon favoured the lion.

66

This was eventually rejected around July 1804 in favour of the eagle, on the urging of Vivant Denon. The eagle not only evoked Charlemagne, but inspired the imagination of contemporaries, and placed Napoleon’s reign firmly within the tradition of the universal empires of the past.

67

That was not to be the only symbol, however. In June 1804, when the coat of arms was being designed, Cambacérès proposed the bee. In ancient times, the bee was a symbol of immortality and resurrection, but people also remembered that metal jewellery in the form of bees had been discovered in the tomb of the father of Clovis, Childeric I (440–81), at Tournai in 1653, during the reign of Louis XIV.

68

It is more likely that what was discovered were cicadas or crickets, and they were not emblems but votive objects placed on the royal clothes: insects enabled the soul of the departed to fly more easily towards heaven.

69

The bee was nevertheless a symbol that drew on the past, even if contemporaries had incorrectly interpreted its historical significance. It was also meant to be a metaphor for France: the beehive was the Republic, with its leader a hard worker. And perhaps it was hoped that the French would be as submissive as drones working for the queen. The bee enabled the regime to draw a link between the furthest reaches of French history – the Merovingian dynasty founded by Childeric – and the present.

On 15 July 1804, Their Majesties put on a display for the people. Napoleon arrived at the Church of the Invalides in the uniform of a colonel of the Guard, riding a horse covered in gold, his boots resting in stirrups of solid gold. Josephine was in a carriage drawn by eight horses, bedecked in diamonds. They assisted at a mass by Cardinal Caprara, the papal legate – Napoleon was sitting on a throne during the proceedings – after which the Emperor personally awarded the first civilian Legion of Honour. Julie Talma, the wife of the well-known actor François-Joseph Talma, called the ceremony the ‘distribution of the trinkets’.

70