Citizen Emperor (30 page)

Authors: Philip Dwyer

Jérôme faced a similar dilemma to his brother, but reacted very differently. On Christmas Eve 1803, he married an American woman, a rich shipowner’s daughter from Baltimore, Elizabeth Patterson.

129

Jérôme was nineteen at the time, had left the naval vessel on which he was serving to take in the United States and had met and quickly married Elizabeth even though, according to French law, he was not legally of age (the Civil Code stated that in order to marry one had to be twenty-five or else have the permission of one’s parents). Like Lucien, Jérôme married without his brother’s knowledge. When he learnt of it through a dispatch from the French consul general in America, Bonaparte simply refused to recognize the marriage and obliged his mother to sign a statement in front of a notary declaring that she had not given her consent to the marriage (a little rich coming from a man who had married a woman the family disapproved of).

130

When Jérôme brought his wife back to Europe from the United States in April 1805 (they landed in Portugal), Napoleon ordered him to travel overland to Italy (through Spain and southern France), and insisted that Elizabeth not leave the ship. If they tried to head for Paris, he instructed Fouché to arrest Jérôme and to send packing Mlle Patterson, as he persisted in calling her, back to America.

131

Jérôme left Elizabeth, pregnant, in Lisbon, no doubt convinced at this stage that he could persuade his brother to change his mind. He did not. Jérôme may have loved Elizabeth – he certainly wrote to her saying that he loved her as much as life itself

132

– and he may have said that he would rather kill his own children than declare them illegitimate,

133

but at some stage he gave in to his brother’s pressing demands. If he had been wilful as a youth, always refusing to toe the line, it now seems he was incapable of bucking his brother, at least on this issue. Napoleon was probably dangling before him the prospect of a kingdom if he did as he was told. It took all of ten days for Jérôme to change his mind.

Napoleon was ‘generous’ in victory. ‘My brother,’ he wrote adopting an imperial tone, ‘there is no fault that sincere remorse cannot efface in my eyes.’

134

He then promised a pension to Elizabeth of 60,000 francs a year. What that reveals of Jérôme’s character – a certain opportunism, a lack of resolve, an inability to live independently outside the family circle (unlike Louis) – is academic, but it does not say much. When faced with the choice between love and ambition, he was crass enough to choose ambition. One contemporary at least thought him the most proud, the most impolite, the most ignorant and the most ambitious young man he had ever encountered.

135

Jérôme saw Elizabeth only one more time, in 1822 when they ran into each other in a museum in Florence. They did not stop to talk; Jérôme was with a new wife. The declarations one can find in his earlier letters to her – ‘you have a place in my affections which no power, no political expediency can take away’ – had been long forgotten.

136

At the dinner reserved for members of the family after the proclamation of the Empire, the marshal of the palace, Michel Duroc, arrived to inform everyone about the new protocols. Their brother would have to be referred to as ‘sire’. Joseph and Louis were accorded the title ‘prince’, while their respective wives – Julie and Hortense – were to be called ‘princess’. It is possible that Joseph at first refused the title, but he soon came round.

137

Caroline, twenty-two years of age and now married to Murat, could not bring herself to call the daughter of a soap merchant (Julie, the wife of Joseph), as well as Josephine’s daughter, ‘princess’, especially since she herself would be officially known only as ‘Mme la Maréchal’. Elisa Bacciochi, five years older than her sister, described as ‘haughty, nervous, passionate, dissolute, devoured by the double hiccough of love and ambition’, felt the same way.

138

Her title, since she was married to Colonel Bacciochi, would simply be ‘colonelle’. When Napoleon finally arrived for dinner, he could see they were visibly upset.

139

Rather than placate them, he just rubbed it in their faces, deliberately addressing Julie and Hortense as ‘princess’ as often as he could. Caroline’s rage eventually transformed itself into tears; she had to gulp down large glasses of water in an effort to get a hold of herself, but tears kept coming back. During this ordeal, according to one witness, Napoleon ‘smiled rather maliciously’.

140

The next day, the three siblings – Napoleon, Caroline and Elisa – had a violent quarrel in Josephine’s salon, resorting now and then to their Corsican patois to insult each other. Caroline complained to Napoleon that he had condemned them to ‘obscurity, to scorn’, while others were being covered in honours and distinctions. It was probably on this occasion (or the preceding evening, we are not sure) that Napoleon replied, ‘Really, if one listened to my sisters, one would believe that I had robbed my family of the heritage of the late king, our father,’ an epigram repeated all over Paris it was thought so witty.

141

By this stage, Caroline, to bring home her point, managed to faint right there on the floor, while Elisa let out piercing cries. Caroline seems to have known that a little histrionics went a long way with her brother. The very next day (20 May), an article appeared in the

Moniteur

announcing that Caroline, Elisa and Pauline were also being given the title of ‘princess’. (It was at this time that Pauline, who was in Italy when she learnt of the title, changed her name from Paulette, as till then she had been commonly known.) To add to the burlesque, their husbands were not elevated to the rank, at least not yet.

As for Letizia, in Rome, she decided that she would not attend the planned coronation. Part of her disapproved of the whole thing, possibly out of fear that her son was getting a little too big for his boots – she had nightmares about some fanatical republican assassinating him

142

– but part of her seems to have been upset over the lack of distinctions and the lack of money coming her way. Napoleon’s uncle, Letizia’s half-brother Cardinal Fesch, wrote to him on the subject in July 1804.

143

If the daughters had become Imperial Highnesses, was it appropriate that the mother of all these princes and princesses be considered a simple subject? Besides, her entourage were already unofficially referring to her as ‘Majesté’.

Napoleon was put on the spot, and he now had to find a title for his mother. After consulting with the experts and looking at books on protocol and etiquette, no easy thing since this was setting a precedent, Letizia was given the title ‘Madame’. However, during the

ancien régime

‘Madame’ had been a title used to designate the daughters of the king. In case Napoleon one day had a daughter, therefore, the words, ‘mother of His Majesty the Emperor’ were tacked on to the end of ‘Madame’. It was, admittedly, a little long and was never really used; Napoleon always referred to her as ‘Madame’. The title ‘Madame Mère’ (Madam Mother) that eventually came into use was never official.

144

Nor was it something that pleased Letizia very much. In fact, she was mortified by its spectacular lack of brilliance, and was not afraid to let her son know how displeased she was. But then she was a hard woman to please at the best of times; even a monthly pension of 25,000 francs did not put a smile on her disgruntled countenance.

A constitutional monarchy of sorts, even if it did contain the germ of an autocratic system, had at last been reached; the Revolution had been consolidated; the counter-revolution had been dealt a hefty blow not only through the founding of the Empire, but particularly through an accord with the Catholic Church; a certain number of revolutionary principles had been put into practice such as equality before the law and freedom of religion; the sale of nationalized Church lands (

biens nationaux

) had been guaranteed; and a new legal system codifying and consolidating the gains of the Revolution had been introduced.

145

Napoleon was thus seen as the person most responsible for steering the ‘vessel of the Republic’ into safe harbour, ‘sheltered from all storms’.

146

The democratic experiment that had been the Revolution had reached its limits; it was time to replace the political anarchy that had reigned over the last ten years with a durable authority.

147

That authority should reside in one person, with enough force to bring about a ‘social pact’ and to consolidate the country’s institutions on solid foundations.

148

‘It is the product of his genius, and at the same time a just reward for his work.’

149

What other system, one pamphleteer asked, offered such stability and such hope?

150

The Empire was therefore proposed as a more efficient alternative to both monarchy and democracy, and Napoleon presented as a vehicle of hope, a force that would create a better world.

151

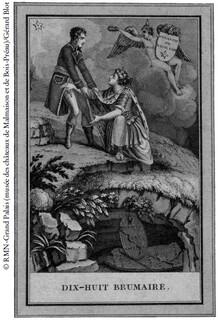

Dix-huit Brumaire

(18 Brumaire). Frontispiece to Louis Dubroca,

Les quatre fondateurs des dynasties françaises, ou Histoire de l’établissement de la monarchie française, par Clovis . . . Pépin et Hugues Capet; et . . . Napoléon-le-Grand . . .

(The four founders of the French dynasties, or The history of the establishment of the French monarchy), Paris, 1806. Note the broken tablets at the bottom of the frame representing the three previous dynasties – Merovingian, Carolingian and Capetian. The message is simple but clear: Napoleon, the successor to these dynasties, is helping France get back on its feet.

It was not the fall of Robespierre in 1795 that brought the Revolution to an end, nor did it end in 1799 with the coup of Brumaire, even if one of the first things Bonaparte did was to declare it over. Nor did it end in 1802 with the Peace of Amiens. The Revolution came to an end in 1804 with the proclamation of the Empire, and more powerfully and symbolically, in December of that year during the coronation ceremony at the Cathedral of Notre Dame. At that moment, when Napoleon crowned himself emperor, the political principles of 1789 were finally realized.

152

* Gideon means ‘destroyer’ or ‘mighty warrior’.

8

‘The First Throne of the Universe’

The Trial of General Moreau

Ten days after the proclamation of the Empire, on 28 May 1804, the trial of Moreau and Cadoudal, along with forty-five others accused of plotting to kill Napoleon, opened at ten in the morning. Pichegru was not present: he had been found dead in his cell. A black silk cravat and a little baton were found around his neck; he had garrotted himself.

1

Napoleon immediately ordered a public inquest. There is no evidence that Pichegru was murdered, or that Napoleon could even have benefited from his murder, but that did not stop some from believing his death had been ordered by the Emperor.

2