Citizen Emperor (54 page)

Authors: Philip Dwyer

As a result of Napoleon’s outstretched hand, Alexander’s mood was transformed overnight from despondency to excitement. He had lost tremendous personal and political prestige through two major defeats in as many years, so Napoleon was offering him in some respects a way out. He could save face by concluding a treaty which not only was profitable to Russia but would be the harbinger of international peace.

The Partition of the World

Tilsit (today Sovetsk) was then a small town on the left bank of the River Niemen that marked the boundary between Prussia and Russia. The river was also the official demarcation line between the opposing forces; troops were lined up on either side of the river facing each other, so Napoleon came up with the idea of building a raft and meeting in the middle. If it had taken place elsewhere, rather than on a raft, the meeting would quickly have raised concerns about etiquette, prestige and status.

55

On this elaborate raft, about four by six metres, stood a small central salon with two antechambers on either side; the salon was made of wood and painted white to resemble a tent. On one side was painted an ‘N’ and on the other an ‘A’. Everything was ready by about 12.30 in the afternoon on 25 June 1807, and timed so that the two emperors, each accompanied by a small entourage, would leave their respective shores simultaneously and arrive at the raft at the same time, the first meeting of two European monarchs since 1532.

56

It must have been a strange sight. Alexander, tall, Napoleon shortish; Alexander speaking fluent French, Napoleon speaking it with a heavy accent.

57

If Napoleon was driven, Alexander was vain, full of

esprit

, the expression of the day and, according to one close observer, not quite all there.

58

But neither was showing his true colours. The meeting, which took place in the salon that was constructed on the raft, lasted two hours, unburdened in some respects by court etiquette and the eyes of courtiers – there are no contemporary accounts. Once the initial encounter was over, and for the next two weeks, they spent a good deal of time together reviewing troops, exchanging presents and decorations, attending the theatre, dinners, parades and balls together. The Imperial Guard, on Napoleon’s orders, held a banquet for their Russian counterparts.

59

The festivities were designed not only to flatter Alexander, but also to portray an idealized relationship between the two rulers. The last evening they spent talking at great length, although we know nothing of what was said between the two men.

60

This was staged diplomacy at its best. Napoleon and Alexander were playing conciliatory roles, both expressing ideas that they thought the other wanted to hear, and both came away seemingly infatuated with the other. But one has to wonder to what extent those sentiments were sincere. Alexander is supposed to have said something like, ‘If only I had seen him [Napoleon] sooner! The veil is torn asunder and the time of error is passed.’

61

For his part, Napoleon wrote to Josephine to say that Alexander was a ‘very handsome and good but young emperor’.

62

We know, however, that in private Alexander considered Napoleon a parvenu. Behind the scenes he was assuring those in his entourage that ‘We shall see his fall with calmness’, or he made references to the ‘true moment’ when they would strike against Napoleon.

63

One should consequently treat with some scepticism the assertion that Alexander was charmed by Napoleon (and vice versa). The problem with Napoleon is that, more so than Alexander, he took the diplomatic discourse at face value. In the grander scheme of things, he was disadvantaged. Alexander was surrounded by advisers, not to mention the aristocracy and the diplomatic corps, who hated Napoleon and the French.

The whole spectacle at Tilsit was meant to place Napoleon and Alexander on the same level; they were now portrayed as royal allies, as equal brothers. In his correspondence, Napoleon addressed Alexander (as he did other sovereigns of Europe) as ‘my cousin’, as though they were members of the same family. (After his marriage to the Austrian princess Marie-Louise, Napoleon would refer to Louis XVI as his ‘poor uncle’.)

64

Even the act of embracing, which Napoleon did to Francis after Austerlitz and to Alexander at Tilsit, was meant to put him on an equal footing. Tilsit was, therefore, quite a diplomatic coup for Napoleon. Until then, Alexander had refused to recognize his status as emperor, but now not only was he obliged to do so in a public manner, he had to agree to treat Napoleon as an equal in the treaty stipulations that followed.

Tilsit was in effect made up of three treaties, two agreed by France with Russia and one with Prussia. The Russian alliance was, in some respects, breaking with recent tradition; France had played the Austrian card to the exclusion of the Russians for decades. There were people in Napoleon’s entourage who still thought that this was the best option for France. Armand de Caulaincourt, sent to Petersburg as ambassador after Tilsit, warned Napoleon that French behaviour was having an adverse impact on European public opinion.

65

Russia had not been crushed, as had Austria and Prussia, and so did not have to come to the negotiating table, except that it was tired of the war. It meant that Russia came away with more territory than before it entered the war – a sizeable chunk of Prussia and the annexation of Finland (which had belonged to Sweden, at war with France), in return for a promise to close Russian ports to English goods. There was talk of an eventual partition of the Ottoman Empire, but as we shall see this was an ever-moving feast with Napoleon, who could agree to it one day and change his mind the next, and the issue was probably raised at the conference table as a sort of lure to get Alexander more interested in an alliance. Napoleon also gained from the alliance, although only in terms of prestige. His title and his Empire were now recognized by Russia. Tilsit was, on the surface, a partition of the Continent between the two emperors, France dominating western and central Europe, while Russia dominated the east. This was not a particularly new idea and recognized what already existed. As early as 1801, political commentators had remarked that mainland Europe was divided between the two powers, so that the idea of a bi-hegemony had become quite current.

66

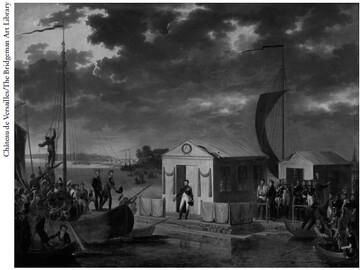

Adolphe Roehn,

Entrevue de Napoléon Ier et du tsar Alexandre Ier de Russie sur le Niémen le 25 juin 1807

(Meeting of Napoleon I and Tsar Alexander of Russia on the Niemen, 25 June 1807), 1807. The raft was decorated with garlands and wreaths, the letters ‘A’ and ‘N’, and French and Russian flags. There was no sign of the Prussian flag, despite being on Prussian territory. The threatening clouds unwittingly evoke troubles that lay ahead. The Niemen symbolized for the next five years the demarcation point between East and West. Interestingly, in this painting, and unlike the highly choreographed meeting that saw the two emperors approach and board the raft simultaneously, Napoleon is depicted waiting for Alexander’s arrival, placing him in a position of ascendancy.

With Russia on his side, Napoleon was hoping for a free hand in central Europe. It was not that he did not already have one, but Prussia and Austria were less likely to cause problems knowing that Russia was not going to ally with them. More than that, though, Napoleon was hoping that Russia would make Britain think twice about continuing the war against France.

67

The former stratagem was unnecessary and the latter proved unfruitful.

68

Alexander, on the other hand, was obliged finally to recognize both the French annexations and Napoleon’s imperial title, as well as the royal titles of his three brothers. But he also believed that peace would now reign over Europe,

69

that the treaty would benefit his people by allowing him to continue to reform Russian society, and that he would be given free rein to expand eastwards towards Constantinople.

70

The second treaty was signed two days later, and concerned Prussia. Once peace was decided, it was simply a question of agreeing on the price. Alexander was faced with a moral dilemma of sorts; he did not want to appear to abandon his ally Frederick William, but he had no real choice.

71

Prussia was in no position to continue the campaign, and Russia was not prepared to continue the struggle alone (nor was it able to at this stage), all the more so since Napoleon had been getting cosy with the Ottoman Empire. Frederick William was present at Tilsit, but was not invited to take part in the negotiations. While the two emperors were meeting on the raft, the King of Prussia, on whose land this meeting was taking place, was obliged to wait on the bank of the river, wrapped in a Russian overcoat, to learn the outcome of the discussions.

72

After two hours, the Tsar came ashore to inform him that Napoleon would see him, but only on the following day.

Anonymous,

Diné donné par Sa Majesté Napoléon I.er . . . à Leurs Majestés Alexandre I.er . . . Frédéric [Guillaume] III . . . Grand Duc de Berg

(Dinner offered by His Majesty Napoleon I . . . to Their Majesties Alexander I . . . Frederick [William] III . . . and the Grand Duke of Berg), 1807. In this engraving, Napoleon is the equal of his eastern European counterparts, Alexander I and Frederick William IIII, dining together in an intimate setting, as though they were friends. Such a dinner never occurred, and the scene belies the hostility that Frederick William and to a lesser extent Alexander felt towards Napoleon.

The next day, Frederick William was invited by Napoleon to board the raft for an audience, but he was treated little better than an envoy, and was made to wait in an antechamber while Napoleon and Alexander saw to some unfinished paperwork. When the two finally met, there was no dialogue, no discussions or negotiations. Instead, Napoleon badgered Frederick William about the mistakes he and his generals had made during the campaign. He did not even deign to inform the king what he had decided. A week later, in a desperate and rather pathetic gesture, Frederick William sent his wife, Queen Luise, ‘to save Prussia’, to intervene, to plead with Napoleon not to annex territories that had been with the kingdom for centuries.

73

The queen used all the charm and coquettishness that she was capable of, and in her own words ‘cried for the love of humanity’, but to little effect. Napoleon was careful not to say anything that could later be used to wrest concessions from him.

Luise and her husband suffered one humiliation after another; whenever the three monarchs rode in public, Frederick William trotted behind Napoleon and Alexander, as though he were a minor German prince. The Prussian royal couple were put up in a flour mill, one still being used by French troops to grind grain and housing the mules of the miller. ‘It was a competition to see who could make the most noise to interrupt the sleep of the poor King and his beautiful queen.’

74

Prussia was reduced to a size on a par with Bavaria, losing half its territory and its population, so that it became little more than a buffer state between the French and Russian empires. Former Prussian territory in the west was incorporated into the newly created Kingdom of Westphalia, with a population of about two million people, while most of the Polish lands in the east went to create the Duchy of Warsaw.