Citizen Emperor (50 page)

Authors: Philip Dwyer

Davout should have been supported by Bernadotte, who commanded a corps of 20,000 men; he was near by and heard the sound of the guns. Bernadotte had, moreover, received orders from Berthier that morning to join Davout. He simply chose to ignore them, as well as Davout’s repeated pleas for assistance.

89

Instead, he followed to the letter Napoleon’s earlier orders to join him at Apolda, although he was so slow in getting there that it took him all day to cover the twelve kilometres that separated them. He did not reach Jena until after the battle was over.

90

Why Bernadotte was not severely punished, as the army expected, is difficult to say.

91

Napoleon later admitted that he had signed an order for Bernadotte’s court martial but that he later tore it up.

92

Was he thinking of his first love, Désirée, now the marshal’s wife, or did he believe that Bernadotte would try to atone for his conduct by recognizing that he had performed disgracefully?

93

If so, he appears to have judged the man well; Bernadotte ruthlessly pursued the retreating Prussians over the coming weeks.

Napoleon did not find out what had happened until later in the evening when he got back to Jena. Waiting in front of an inn where he planned to spend the night was an officer from Davout’s staff who explained that Davout had fought and defeated the main body of the Prussian army forty kilometres away at Auerstädt. Napoleon at first refused to believe it but soon had to face the reality of the situation, paying tribute to Davout in the next day’s bulletin.

94

But that was all the praise Davout was to receive. As had happened in the past – think of Moreau and Hohenlinden – Davout’s victory was completely sidelined. In contemporary reports, the two separate battles were reduced to one – Jena – with Auerstädt becoming the right wing of a larger battle. Indeed, from his very first bulletin, Napoleon only ever spoke of Jena.

95

Even at the height of his power, he was jealous of others’ successes and, despite getting on well with Davout, was not about to let one of his lieutenants outshine him. This is not to say that he did not richly reward Davout for his services – he was later made Duc d’Auerstaedt – but his praise remained private.

96

Auerstädt was never to play a large role in the regime’s propaganda and was more or less forgotten (there is no Pont d’Auerstädt in Paris, there is no monument of any kind, and no paintings were commissioned). As we shall see, the defeat of Prussia was to be represented in different ways.

A few days later, on 18 October, on his way to Berlin, Napoleon stopped to visit the nearby battlefield of Rossbach. Rossbach was a defeat inflicted on the French by Prussia in November 1757 during the Seven Years’ War, and it had profoundly marked French popular memory to the point that there were constant calls throughout the second half of the eighteenth century to have the blight washed away. That Napoleon was finally able to do this was a considerable achievement; he ordered that the memorial to the Prussian victory be dismantled and transported back to Paris.

97

This too was a deliberate attempt on his part to draw a comparison between himself and Frederick the Great, and was to become a prominent theme in Napoleonic propaganda over the coming years.

98

Pierre Antoine Vafflard,

L’Armée française renverse la colonne commémorative de Rossbach, le 18 octobre 1806

(The French army topples the commemorative column of Rossbach, 18 October 1806), Salon of 1810.

A Triumphant Napoleon . . .

About ten days after the collapse of the Prussian army, on 24 October 1806, the French made their entry into Berlin.

99

Napoleon arrived three days later – he gave Davout the honour of leading his corps through the city first – on a glorious autumn day, church bells ringing, guns resounding, receiving the keys of the city from Prince Hatzfeld (arrested shortly afterwards for spying). Unlike his treatment of Vienna after the victory of Austerlitz, Napoleon made a point of making a triumphal entry into Berlin, underlining Prussia’s defeat with a humiliating military parade through the Brandenburg Gate (on top of which was the Quadriga – a set of bronze statues of four horses representing peace – but not for much longer), and riding down Unter den Linden.

100

It was about three in the afternoon; a large crowd – ‘the whole population of Berlin’, according to one witness

101

– drawn by a mixture of sorrow, admiration and curiosity, had turned out to see the successor of Frederick the Great, looking a little heavier than he had just a few years before.

102

The humiliation was made worse by the fact that only a week previously a rumour had reached Berlin that Napoleon had been destroyed at Jena. The city was rudely brought back to reality.

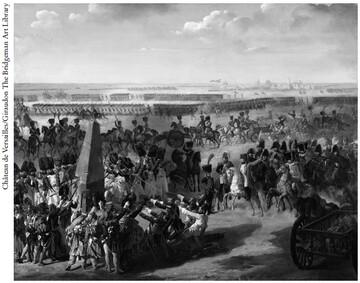

Charles Meynier,

Entrée de Napoléon Ier entouré de son Etat major dans Berlin, 27 octobre 1806, il passe par la porte de Brandebourg

(Entry of Napoleon I into Berlin surrounded by his chiefs of staff, 27 October 1806, he passes by the Brandenburg Gate), 1810. The citizens of Berlin are portrayed greeting Napoleon with an enthusiasm that is belied by contemporary reports that depict a mournful crowd.

103

Berlin was considered one of the most beautiful European cities of its day, with the old quarter, Friedrichstadt, made up of large streets lined with beautiful houses and imposing buildings, including the royal palace.

104

The town was also renowned for the Tiergarten where even during the week the inhabitants gathered, especially in the cafés that surrounded the park. One could find women drinking coffee and working on their needlepoint, and men drinking beer and smoking pipes. The population of Berlin had tripled over the past hundred years, with more than 150,000 inhabitants when it was occupied by the French. At the time, Berlin was a mixture of old and new, the new being the private residences one could find along the Friedrichstrasse and Unter den Linden, most of which were built under Frederick the Great, while the old quarters were overcrowded and dirty. A constant complaint of visitors was the smell emanating from the stagnant waters of the streams and fouling the new quarters.

105

When the French arrived, however, the streets were deserted, at least according to some accounts.

106

Thousands had fled the enemy’s arrival at the signal given by the court, which decamped to Memel, then no more than a small seaport on the Baltic near the Russian border on the outer limits of the kingdom.

At Potsdam, where Napoleon spent several days, he went to visit the tomb of Frederick the Great, in the Garnison Kirche.

107

According to witnesses, Napoleon stood before it, silent, alone with a select few from his entourage, in contemplation for about ten minutes.

108

The imperial propaganda machine made much of this scene. Images of Napoleon deep in thought before the tomb were produced in the months and years that followed. It was both a mark of respect for Frederick as general and sovereign and a means of enhancing Napoleon’s own reputation by obliging people to compare him to Frederick, one of the greatest generals of the eighteenth century. This is how Napoleon preferred to portray his defeat of Prussia, by capturing the moment he stood before Frederick’s tomb. It is a moment that says two things: that Prussia’s former greatness was dependent on one man, just as France’s present glory was dependent on Napoleon; and that Napoleon was the more brilliant of the two.

109

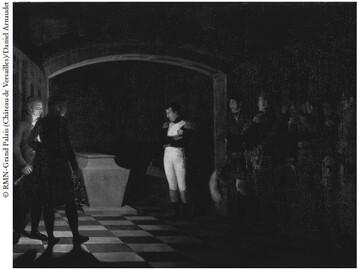

Marie Nicolas Ponce-Camus,

Napoléon Ier méditant devant le cercueil de Frédéric II de Prusse dans la crypte de la Garnisonskirche de Potsdam, 25 octobre 1806

(Napoleon I meditating before the tomb of Frederick II of Prussia in the crypt of the Garnison Kirche in Potsdam, 25 October 1806), 1808. The painting was meant to portray Napoleon in marked contrast with the portraits of the kings of Europe, simple in his dress, which made him the son of the Revolution.

. . . Encounters an Obdurate Frederick William

At the beginning of the campaign against Prussia there were signs that public opinion in France was tiring of the incessant wars.

110

Napoleon had, after all, promised peace. If Austerlitz was greeted with muted enthusiasm, news of Jena received an even cooler reception.

111

The authorities did not even bother organizing a public celebration for the victory at Jena-Auerstädt. Napoleon had to instruct the prefect of the Seine, Frochot, to ‘facilitate the explosion of enthusiasm’.

112

Police reports made it plain that, in some centres at least, the populace was sick of the war, and this before any military defeats or reverses had taken the shine off Napoleon’s aura. Some believed the victory over Prussia would serve only to make the Emperor ever more intractable and that peace would be postponed even further. One officer later argued that after the Prussian campaign educated officers in the army realized that Napoleon’s promises were empty and that they no longer fought for peace but to satisfy his unbounded ambition.

113

This individual may have been writing with hindsight, but there is enough to indicate that people were becoming wary of what they saw as Napoleon’s expansionist designs.

Just how widespread this feeling may have been is impossible to judge, and in any event usually consisted of little more than disgruntled individuals venting their frustrations.

114

It is, however, possibly one of the reasons why the Senate sent a delegation to Berlin in November 1806 to petition Napoleon not to continue the war in the east, urging him to make peace.

115

Napoleon’s response was to present the delegation with Frederick the Great’s sword, which he reportedly said he would rather have than twenty million francs. Napoleon did not tell anyone that he intended taking the sword, along with a few other decorative objects; he simply took them and had them transferred to the Invalides in Paris.

116

If it was his way of allaying any fears the Senate might have had, it was an odd way of doing so.

117