Citizen Emperor (48 page)

Authors: Philip Dwyer

Joseph was not the only member of the Bonaparte family to benefit from the creation of the Empire. In May 1806, rumours were flying around Paris and Amsterdam that Louis would be made King of Holland. This did indeed occur the following month, but not without intense and public political discussions in Holland about the transformation of the two-centuries-old Republic into a monarchy, a good deal more intense than what had occurred in France in 1804.

41

If Napoleon offered Louis the Dutch throne it was in part because no other member of his family could fill the post. Lucien was out of favour and would not re-enter the family fold; Jérôme was only twenty-one years of age, too young and too inexperienced to take up a position of such responsibility; Joseph was already ensconced in Italy, as was Napoleon’s stepson, Eugène. The only male member of the family not yet to have an important post, Murat, was soon to become Grand Duke of Cleves and Berg, but he could hardly take precedence over Napoleon’s brother. Louis too hesitated before accepting the position, but he gave way in the end to Napoleon’s insistence, not however without a public humiliation.

A witness tells of a curious family scene that took place at Saint-Cloud on 6 June 1806, the day after the official ceremony proclaiming Louis king.

42

Louis’ son, Napoleon Charles, nicknamed the

Petit-Chou

(little darling), who would die the following year of croup, had learnt a fable that he performed before Napoleon and his guests seated at table for lunch. The fable in question was Aesop’s ‘The Frogs Who Desired a King’. Napoleon thought the story was hilarious, and in doing so revealed a great deal about what he really thought of his brother. Frogs were traditionally used to caricature the Dutch, but in this fable they demanded a king of Jupiter, who sent them instead a piece of wood. When they complained, he sent them a crane, which proceeded to eat them all. The allusion was clear, at least to Napoleon: the Dutch were stupid and they were about to get a king who would do his bidding. As for Louis, Napoleon did not appear to set much store by him. ‘Everyone knows’, he wrote shortly before annexing Holland in 1810, ‘that without me, you are nothing.’

43

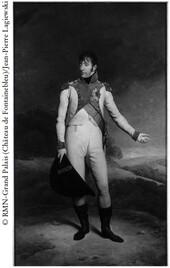

Charles Howard Hodges,

Louis Napoleon, King of Holland from 1808–1810

, 1809.

Louis had traits in common with his elder brother – he was rather a dreamer, a bit melancholic and maladroit – but he was by no means as dynamic. He had a reputation for being lazy (not entirely deserved), was a hypochondriac and had a love of sumptuousness that he shared with some of his other siblings (but not Napoleon). Napoleon had a sincere fondness for him, while Louis admired, even imitated, Napoleon in just about everything he did, including his physique (much like Napoleon, Louis was becoming flabby and overweight). For a while, Louis attempted to maintain his brother’s work rhythm – getting up at five in the morning, holding audiences from seven to nine, Council of State from nine to twelve and so on – but he had to abandon that schedule after a year as his health deteriorated. Louis, in other words, took to heart his functions as King of Holland and worked (sometimes) selflessly for his new subjects, attempting to fit in with the Dutch as much as possible, trying to win them over after a cool reception on his arrival in 1806. He had a tough job of it, not least because he was in a sort of constitutional limbo, having been declared king while the Dutch republican constitution was left largely unchanged, and also because of the demands placed on him by his brother.

44

Napoleon tried to control Louis’ life in much the same way that he tried to control the lives of all his siblings as well as those in his close entourage. It was only once he became king that Louis began to stand up for himself, to grow into his role, to take on his brother, to argue with him, even to reply to his letters in a sarcastic tone. This newfound independence irritated Napoleon greatly and from that moment things began to sour.

When Napoleon rebuked his brothers and sisters, which was often, he did not generally hold back. ‘I am angry,’ he would write, or ‘you understand nothing about the administration’ or again, ‘You are going about this like a scatterbrain [

un étourdi

].’

45

Within a short time of Joseph’s arriving in Naples, Napoleon was already accusing him of being too soft, insisting on more vigour in his dealings with the people of Naples, and suggesting that he was a ‘do-nothing king’ (

roi fainéant

), an evident and not particularly flattering allusion to the Merovingian kings of the Middle Ages.

46

The same tone can be seen in his letters to Louis, whom he dubbed a ‘prefect king’ (

roi préfet

).

47

One of the first pieces of advice Napoleon offered his brother was not to be kind. ‘A prince who in the first year of his reign is considered to be kind, is a prince who is mocked in his second year.’

48

Even when his siblings did carry out his orders to the letter, Napoleon’s reactions were often ungracious.

Napoleon’s brothers and sisters responded in different ways to these verbal assaults. Joseph attempted to flatter his younger brother to bring him onside or simply ignored him. Lucien left the clan and never returned. Louis became recalcitrant, arguing that by devoting himself to the wellbeing of his people, he would make himself worthy of his brother’s name.

49

Jérôme became defensive; Joachim and Caroline Murat were to become more and more distant. Only Eugène, Pauline and Elisa kept on good terms with Napoleon, although Pauline’s libertine behaviour can be interpreted as a form of revolt. The key to understanding his ‘system’ – a word used by Napoleon himself to describe the family alliances within the Empire – is straightforward: Napoleon wanted his siblings to be extensions of him. He almost never gave them enough autonomy to rule in their own right – although they sometimes ignored his demands and ruled as they saw fit – and he always expected them to obey him unswervingly, to impose enormous sacrifices on their own peoples for the sake of the glory of France and Napoleon.

Napoleon used his family in his dynastic politics. He pressured, cajoled and bullied his relatives into accepting marriages with the sovereign houses of Europe for the sake of political alliances that would cement his dynasty, mobilizing any family member who was of marriageable age.

50

This was quite typical of French and European dynasties. Both Louis XIV and Louis XV had installed members of their family on the thrones of Spain, Naples and Parma (which Napoleon set about undoing). In January 1806, Eugène was married to the daughter of the King of Bavaria, Augusta Amelia (one of the rare couples in the grand scheme of things who formed a lasting, loving bond). The marriage was celebrated in great pomp in Munich. In April 1806, Josephine’s cousin Stéphanie de Beauharnais, with whom Napoleon was a little in love, was married to the Crown Prince Karl, Grand Duke of Baden. The family was thereby allied to two powerful southern German states that had been enlarged and transformed into kingdoms by Napoleon in the territorial reconfiguration that followed Austerlitz. To consolidate the German bonds, Jérôme, whose marriage to Elizabeth Patterson was annulled by the Archbishop of Paris, was married off to Catherine, the daughter of King Frederick of Württemberg (they too seem to have formed a loving couple, although it did not prevent Jérôme from playing the field).

51

In 1808, one of Murat’s nieces, Marie-Antoinette Murat, was married to a prince of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, while another of Josephine’s cousins, Stéphanie Tascher de La Pagerie, married the Prince of Arenberg. In 1810, her brother, Louis Tascher de La Pagerie, married the daughter of the Prince Regent of Leyen. Not all these marriages were happy, but the stakes were high and the feelings of Napoleon’s relatives counted for little.

Napoleon had been thinking of creating a federal system, a ‘league’ as he called it, to replace the sister republics of the revolutionary era before Austerlitz, but his victory gave a certain impetus to the idea of a political system based on bloodline, and made it more difficult for the minor princes of central Europe to say no to his requests. The fundamental problem with this system of alliances was that most of the personalities in place, despite being close relatives, were hardly well disposed towards either the system or its creator. Like an autocratic head of family, Napoleon knew best, and he treated most of his siblings with barely concealed contempt. They were disinclined to adhere strictly to his economic blockade of Britain (see below). It was contrary to the economic interests of their own subjects, and they sometimes surrounded themselves with ministers and advisers who were openly Francophobe and Anglophile. This was the case, for example, with Louis, who often went to take the waters, and who left in charge ministers who were interested in maintaining good commercial relations with Britain.

52

‘Breathing a Desire for Revenge’

The ‘system’ required Napoleon to maintain the Continent on a constant war footing against Britain. There was once again, however, the possibility of peace when, in January 1806, Pitt the Younger died, exhausted, gout ridden, possibly alcoholic, depressed by the fiasco that was the Third Coalition.

53

He left behind a country divided between those who wanted to continue the war and those who wanted peace. George III was obliged to offer the office of prime minister to Lord Grenville, and the foreign office to a man he detested, Charles James Fox. Along with Henry Addington, they formed a coalition that became known as the ‘Ministry of All the Talents’.

54

In the face of the failure of the Third Coalition and the prospect of going it alone in what would have been an expensive and protracted war, the ‘bloodhounds’, as members of the war party referred to themselves, felt that they had little choice but to join the peace party and urge George III to come to terms with France.

In March 1806, therefore, Fox wrote to Talleyrand informing him that he had had a meeting with a man named Guillet de La Gevrillière, who had come to him admitting a plot to assassinate Napoleon. By English law they could not hold him, and he was writing to warn the French of a potential danger.

55

Talleyrand replied and saw this for what it was, a diplomatic opening. Several letters were exchanged between them and in April Talleyrand suggested that their plenipotentiaries meet at Lille to discuss the possibility of peace.

56

Talleyrand then was instrumental in initiating and pursuing peace negotiations with England in the winter of 1805–6. He brought Napoleon around to the idea little by little, and he kept the hope of a successful outcome burning by always promising more than he had the right to in his informal correspondence with the English representative. He acknowledged the principle of maintaining their respective conquests, gave London to understand that Napoleon would be agreeable to restoring the Electorate of Hanover, and promised that he would do everything so that Malta would remain an English possession (which was not exactly promising much at all as the island was already in English hands and they were hardly likely to give it up). We will pass over the rather strange negotiations that followed, which involved Lord Yarmouth, an unscrupulous rake who was probably in Talleyrand’s pocket, and any discussion about whether Napoleon took the negotiations seriously.

57

The peace negotiations with Britain are of interest only for what follows, namely, war with Prussia.

The outbreak of war between France and Prussia in 1806 was the result of years of mistrust. When Prussia withdrew from the First Coalition in 1795, it created a zone of neutrality in the north of Germany that comprised other states, including Hanover and Saxony, as well as the Hanseatic cities Hamburg, Lübeck and Bremen. But the neutrality zone was essentially hollow. Caught between two powerful states – France in the west and Russia in the east – the Prussian king had limited room for manoeuvre, and Frederick William III had neither the political will nor the military nous to impose himself on northern Germany.

58

Instead, he let Napoleon trample over Prussia’s neutrality on a number of occasions. In May 1803, Bonaparte ordered French troops to occupy the Electorate of Hanover. In October 1804, French troops kidnapped the British envoy to Hamburg, Sir George Rumbold, resulting in a storm of protest from Berlin (Rumbold was accredited to the court of Berlin).

59

The protests must have made an impact on Napoleon because he released Rumbold; it was possibly the only time that he publicly backed down, although this was not much. What he had really been after were the papers in Rumbold’s possession, convinced as he was that the British ambassador was involved in some sort of spy ring. It was nonsense, but coming after the Cadoudal plot this episode was an indication of the depth of Napoleon’s paranoia regarding the British.