Citizen Emperor (70 page)

Authors: Philip Dwyer

Josephine’s inability to procreate and the need to ensure the succession were only the ostensible reasons for divorce. In fact, Napoleon had a fitting heir, Eugène de Beauharnais, whom he had formally adopted in 1806. Far more competent as both ruler and general than any of Napoleon’s brothers, he was the preferred successor. Why then, given the example of Caesar and Augustus, both of whom had adoptive sons, was Napoleon not content with Eugène? Was this really about Napoleon’s ego, as one contemporary suggested, or about geopolitics?

96

In public, Napoleon asserted that ‘adopted children are not satisfactory for founding new dynasties’,

97

but that is patently not the case. Lots of kings in Napoleon’s own day did not have male heirs and their dynasties survived. When Napoleon married Josephine in front of the pope and crowned her empress in 1804, he must have realized that she was not going to bear him any children; they had already been together for seven years. It is true that the Bonapartes might not have accepted Eugène, as Josephine’s progeny, as heir to the throne, but that was hardly a consideration. It is more likely, therefore, that Napoleon wanted a son, and in keeping with his increasingly conservative turn, a son to a princess of royal blood, so that through the boy’s mother he would legitimately belong to one of the reigning houses of Europe. Divorce and remarriage then were about consolidating his rule through an established reigning house, and, as far as that went, the more prestigious the better.

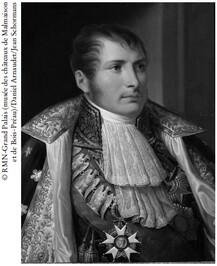

Andrea Appiani,

Portrait du prince Eugène de Beauharnais, vice roi d’Italie

(Portrait of Prince Eugene de Beauharnais, viceroy of Italy), 1810.

Divorce had crossed Napoleon’s mind before: in 1799 when he returned from Egypt; in 1804 shortly after the proclamation of the Empire, when Josephine caused a scandal over Napoleon’s relations with Marie-Antoinette Duchâtel; and again during his stay at Fontainebleau in the autumn of 1807.

98

It is a little ironic then that he considered divorce more seriously about the same time as David’s painting of the coronation appeared at the Salon of 1808. By that stage, rumours of divorce had been circulating for quite some time, no doubt fed by knowledge that Napoleon had put out feelers to Alexander at Erfurt about the possibility of marrying one of his sisters.

99

People contemplating David’s painting in the Louvre speculated about Josephine and Napoleon’s desire to obtain an heir. The liberation of the divorce laws during the Revolution led to a widespread acceptance of divorce, even if the total numbers of dissolutions remained quite low.

100

Napoleon still cared for Josephine and was putting off the inevitable in order not to hurt her. Whenever he was unfaithful he seems to have done what many a cheating husband does – take out his guilt and frustration on his wife. In a letter to a confidante, Josephine complained of Napoleon’s bad moods and the scenes he was making; she discovered that the cause of all the unhappiness was a visit to Paris of the singer La Grassini.

101

In 1808, at the Château de Marracq where Napoleon stayed when dealing with the Spanish royal house at Bayonne, Josephine arrived with two women, Mlles Gazzani and Guillebault, with the intention of handing them over to her husband.

102

It is possible that she thought if Napoleon was going to continue to be unfaithful, then better to choose his lovers herself. He confided later to General Bertrand that the thing he disliked most about Josephine was that she was willing to go to any lengths to keep him attached to her.

Bonaparte had been a romantic through and through, a romanticism that had in part been bruised by Josephine’s own infidelity. She had thereby unwittingly helped to create a cynic and complete his disillusionment with the world. From about the time of Egypt onwards, Bonaparte’s attitude towards women became more callous.

103

When he became head of state, the women he did have serious relations with can be counted on the fingers of one hand – Marie-Antoinette Duchâtel, Carlotta Gazzani, Christine de Mathis, one of Pauline’s ladies-in-waiting, and Marguerite-Joséphine George.

104

But there was something peculiar in his romantic conquests, and that was his need to boast about them.

105

Not only was he capable of recounting in the most intimate detail all that went on in the bedchamber, he was also perfectly relaxed talking to Josephine about them. For the most part they were conquests; Napoleon did not love women. He denied them his time – he was notoriously as quick in bed as he was at the dinner table – and consequently he denied them any intimacy whatsoever. There were, however, two women who managed again to touch that romantic core. Both were Maries – Maria Walewska and Marie-Louise.

The showdown between Napoleon and Josephine took place at the Tuileries on 30 November 1809, a scene that is now part of the legend.

106

Napoleon had returned from Fontainebleau a few days before, and was distracted enough for the prefect of the palace, the Baron de Bausset, to notice. Dinners were held in silence. After one of those dinners with Josephine, and after having dismissed everyone from the room, Napoleon announced that he had decided to divorce her. We do not know what he said but Josephine responded with violent sobs. Bausset, sitting in the salon outside and realizing what was happening, prevented an usher from entering the room and going to her aid. It was Napoleon who opened the door and allowed Bausset to enter, whereupon he found Josephine prostrate on a rug on the floor, emitting what he referred to as ‘heartbreaking cries and lamentations’. It was what contemporaries called ‘an attack of nerves’, the end result of months of anxiety. In any event, it added a melodramatic touch to the end of a relationship that had lasted almost fifteen years. Napoleon asked Bausset, a largish man, to carry her to her apartments while Josephine pretended to faint. Napoleon led the way with a lamp, until they had to descend a narrow staircase leading to Josephine’s bedroom, whereupon the Emperor called over a palace servant to take the lamp; he seized Josephine’s feet while Bausset held her under her arms so that her back was pressed up against his chest and her head resting on his right shoulder. It was at that point that she is supposed to have whispered, ‘You’re holding me too tight.’ Napoleon too played his part as they shed tears together that evening. No doubt there was sorrow and regret on the part of Josephine – she was losing everything after all, although Napoleon would look after her material comfort – and a tinge of regret on his part.

To divorce Josephine, much like other monarchs in other centuries, Napoleon had to obtain the dissolution of the marriage from the pope, and given that he was being held prisoner it was unlikely that he would co-operate.

107

Besides, the precedent had not been very encouraging: Napoleon had in the past unsuccessfully attempted to get the pope to annul the marriage of Jérôme to Elizabeth Patterson. Instead, Napoleon turned to the Parisian ecclesiastical hierarchy, which in January 1810 declared his marriage annulled.

The Bonaparte family must have been delighted. They had never hidden their dislike of Josephine, and had been pushing for divorce for some years.

108

There were others at court, including Fouché, who had also lobbied in favour of divorce, possibly in the knowledge that public opinion believed the Empire would not outlive Napoleon if there were no direct heir.

109

There were, however, those who did not favour divorce. Cardinal Fesch, who took his role seriously, was not convinced by the juridical arguments and insisted that everything had been in order when the pair had married in 1804. It was Cambacérès, a former lawyer, who came to the rescue and found a loophole in the law.

110

He argued that since the religious marriage (which was celebrated shortly before the coronation) did not take place in the presence of witnesses it was clandestine and therefore irregular.

The divorce was not made public right away. We know that Josephine was seen at a ball on 4 December at the Hôtel de Ville looking downcast. On 14 or 15 December, she was obliged to appear before the Council of State, in the presence of Napoleon and the grand officers of the Empire, to declare that she consented to divorce. All the family dignitaries were present, including Letizia, the Emperor’s brothers Joseph, Louis and Jérôme and their wives, Caroline and Murat, Eugène, and Pauline. During this ‘family meeting’ Napoleon took a sheet of paper and read from it. It was when he came to the words ‘She has graced my life for fifteen years’ that he allowed some emotion to come through. Then Josephine in turn read from a sheet of paper but was unable to continue as she was crying so much. Regnaud de Saint-Jean d’Angély, counsellor of state, and secretary of state to the imperial family, had to finish for her.

111

It was a moving occasion, at least for those who liked the Empress.

112

Before she left the Tuileries, Napoleon spent a few hours with her in a tête-à-tête and, according to one account, sobbed on bended knee before her.

113

However, he was in a situation of his own making. He was not obliged to divorce her. This was not about great-power politics or geostrategic necessity. It was about personal ambition. Josephine was sacrificed not at the altar of international relations, but at the altar of Napoleon’s ego. To shed tears, as he did on this occasion, was to suggest that he was the victim, thereby absolving himself from responsibility for his actions.

114

Contemporaries were hardly likely to oblige. The streets of Paris were not pleased by the divorce.

115

In the army, many felt Josephine had been hard done by. ‘He shouldn’t have left the old woman; she brought him luck and us too.’

116

Two days later, Jospehine left the Tuileries in the pouring rain, never to return. Nothing was sadder, as one contemporary put it, than to see the Tuileries widowed by an empress loved by the people.

117

Napoleon spent the next fortnight at the Trianon, a residence in Versailles, dining with her for the last time on 17 December, writing a dozen notes to her before the month was out, attempting to assuage his guilty conscience by a last spurt of affection. Nostalgia perhaps.

118

16

Bourgeois Emperor, Universal Emperor

‘I am Marrying a Womb’

Once the divorce had been decided on, there was the question of a suitable bride. This was going to be the scene of intensive lobbying between various political factions at court.

1

On 26 January 1810, the limits of the problem were laid out by Napoleon at a private council at the Tuileries. A French noble was out of the question; French monarchs invariably married foreign brides. So too was a minor German princess. Napoleon had his sights set much higher. It came down to choosing between a Russian, an Austrian and a Saxon princess.

2

In this he was following the same principle he had laid down for his own relatives: strengthening the dynasty by a policy of alliances through strategic marriage.

Those in favour of a Russian alliance suggested one of the Tsar’s sisters.

3

They were for the most part opposed to an Austrian marriage; it reminded them a little too much of Marie-Antoinette, while Austria had traditionally been an implacable enemy of France. Fouché was able to produce a report on the mood of the Parisian populace that warned against any Austrian connection.

4

Much stronger, however, was the Austrian lobby, which advocated an alliance with Emperor Francis’s daughter, Marie-Louise, eighteen years of age. For Fontanes, who had been a supporter of the return to monarchical forms in France, a marriage with an Austrian princess, after having executed one only sixteen years previously, was a symbolic act of expiation.

5

The lobby supporting the Austrian solution did so with such vigour, however, that Cambacérès suspected Napoleon had organized the whole thing.

6