Citizen Emperor (74 page)

Authors: Philip Dwyer

The public displays were repeated on the day of the boy’s baptism in the transept at Notre Dame on 9 June 1811.

106

Pauline became the godmother. Other than that, only Jérôme and Joseph bothered to make the effort to come to Paris. Louis had chosen the path of self-exile after being thrown off the throne of Holland (see below). Caroline, who was invited to become the godmother, stayed away on the pretext of poor health.

107

In fact, she was upset with her brother for the way he had treated her husband, Murat, and because of the rumours that were going around that the Kingdom of Naples might be incorporated into the Empire. Elisa also stayed in Italy, even though after having lost a child less than a year old she had felt like coming to Paris for a change of air.

108

Napoleon refused her permission, possibly because he did not want his son to come into contact with a woman who could bring him bad luck. The ceremony, which although religious also has to be seen in a political context, took place at the end of the day and concluded with a supper held at the Tuileries, which Napoleon and his wife attended in full regalia, crowns on their heads.

109

It was followed by a concert and then a ball. On the Champs-Elysées,

guingettes

, temporary ballrooms and music kiosks had been set up where the people could attend for free. The costly celebrations were frowned upon at a time when there was high unemployment, an economic crisis and uncertainty about the future.

The Father of the People

The birth of a son – François-Charles-Joseph-Napoléon – would, many thought, transform Napoleon into a less belligerent ruler. A new dynasty was at last in place. Napoleon the Great would eventually give way to Napoleon II, and the rest of Europe would accept the dynasty as legitimate. ‘People sincerely anticipated’, wrote Savary, ‘a period of profound peace; the idea of war and occupations of that sort were no longer entertained as being realistic.’

110

The King of Rome, in other words, was meant to be the guarantor of political stability. Napoleon felt much the same way, believing that with the birth of his son there was a future for his dynasty. ‘Empires are created by the sword’, he told one diplomat, ‘and conserved by heredity.’

111

The arrival of his son saw a concerted effort to present Napoleon as a devoted family man in order to counter the damage done by the constant warring and loss of life (not to mention the numbers of wounded and mutilated who returned home). Napoleon began to refer to himself as the father of his people, at least since Eylau after which he was heard to say in public: ‘A father who loses his children cannot enjoy the charm of victory. When the heart speaks, even glory has no illusions.’

112

The image of the ‘father’ was evoked in the bulletins and proclamations of the Grande Armée, in which Napoleon portrayed himself as a general (and later a monarch) who shared the hardships of his men, who cared for and looked after them, who was moderate and magnanimous, who spared the lives of his soldiers, who aspired to peace, and who wept at the loss of men close to him.

113

This was never more than a line or two – Napoleon had not taken off his boots in a week, he was soaking wet, he was covered in mud, and so on.

114

The idea of Napoleon as ‘father’ had its roots in the traditional association during the

ancien régime

of the monarch with the role of father of his children.

115

The revolutionaries overturned the notion of paternal authority and replaced it with a different idea – ‘fraternity’ and ‘equality’ – so Napoleon’s attempt to recuperate the former kings’ paternal authority can be seen as an attempt to consolidate his own political influence. Over the course of time, the notion among the military of Napoleon as father figure became deeply ingrained.

116

And this went equally for his professed love of peace and his distaste for war. In his letters and public utterances there are an endless number of expressions of peace – ‘I desire peace with all Europe, with England even, but I fear war with no one.’

117

The textual image went hand in hand with a visual transformation of his image after 1810. Considering the toll in men inflicted by the wars, it was no longer appropriate to focus on Napoleon as a military conqueror, as had been the case at the beginning of his rise to power.

Alexandre Menjaud,

Marie-Louise portant le roi de Rome à Napoléon Ier pendant le repas de l’Empereur

(Marie-Louise bringing the King of Rome to Napoleon during the Emperor’s dinner), 1812. There is a sentimentality present in paintings of Napoleon as family man that is entirely lacking in previous portraits of him.

It is only a short step from being called ‘father of the people’ to being described as ‘father of the nation [

patrie

]’.

118

The two notions were in fact developed concurrently. During public festivals commemorating the regime, for example the festival of 14 July, co-opted by Bonaparte and transformed into the Festival of the Concord, the person of the First Consul and the Republic became indistinguishable in the political rhetoric of the day. Local prefects, falling in with the notion propagated by the Brumairians that Bonaparte was the Saviour of the Revolution, associated his name with the Republic in official speeches made during public festivities. It is why supporters of the regime were able to cry out ‘Vive la République’ and ‘Vive Bonaparte’ in the same breath. Speeches from officials constantly reminded the French public how much they owed Bonaparte so that he quickly came to incarnate the nation.

119

Any number of songs composed during the Consulate and the early years of the Empire depicted Bonaparte/Napoleon as a caring father figure who would provide for his people/children.

120

Napoleon increasingly portrayed himself and the nation as one and the same, to the point where, in December 1813, when the Legislative Corps dared criticize him for not pursuing peace actively enough, he retorted, ‘To attack me is to attack the nation.’

121

Again, on New Year’s Day, in the Salle du Trône in the Tuileries, in another scorching attack on the Legislative Corps, he remarked, ‘I alone am the Representative of the People,’ a phrase that he repeated often. He went on to state that ‘All authority is in the throne,’ and that he was the throne.

122

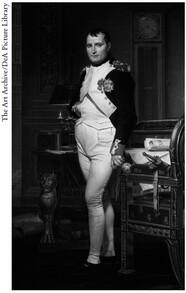

There is no better visual example of Napoleon as paternalistic ruler than David’s portrait

Napoléon

dans son cabinet de travail

(Napoleon in his study), first exhibited in the Salon of 1812.

123

This painting was meant to provide an intimate glimpse into the statesman at work, still in his office late at night while the rest of the world, his subjects, are sound asleep. This ‘fiction of the modern ruler’, as father of the people working late into the night for the benefit of his people, was an image already used by Louis XIV.

124

The glamorous, victorious general has been replaced by an amalgamation of the citizen, an almost bourgeois-like figure, and the royal. We would not even know we are looking at an emperor were it not for the bees on the throne-like chair. In some respects it is a return to the period of portrait painting of Bonaparte as First Consul, when Bonaparte had not yet become the imperial despot.

Jacques-Louis David,

Napoléon dans son cabinet de travail

(Napoleon in his study), 1812. The painting was commissioned by a Scottish admirer, Lord Alexander Douglas. In other words, it was not a piece of propaganda, but rather a private commission. It was only briefly exhibited before being sent to Scotland. In a letter to Douglas, David declared that ‘no one until now has ever made a better likeness in a portrait, not only through the physical features of the face, but also through this look of kindness, of composure and of penetration that never left him’.126

As always, the devil is in the detail: sheets from the Code Napoleon can be seen on the chair next to him; and his sword is lying to one side, as though he were putting his military role away for the moment to look after the administrative side of his duties. The map, the feather pen and a copy of Plutarch’s

Hominus illustri

all point in that direction. Some have preferred to see in David’s painting a ‘profoundly ambivalent’ portrait that implicitly lionizes Napoleon as First Consul while being critical of him as emperor.

125

Note the candles sputtering as the clock shows that it is almost a quarter past four in the morning.

Napoleon deliberately left the candles in his study at the Tuileries alight all night in order to give the impression that he worked at all hours, which was in part true. He did have a habit of getting up at two or three o’clock and working through to six or seven, when he would go back to bed for an hour or two.

127

The newspapers disseminated the image of a ruler who worked tirelessly for his people; the reports gave contemporaries the impression they were dealing with a superior being who ate and slept little. ‘Never had a head of state ruled so much by himself.’

128

Jean-Antoine Chaptal, who resigned from the administration in 1804 when Bonaparte became emperor, wrote of how Napoleon was capable of working twenty hours a day without ever appearing tired.

129

This was not without taking its toll. Napoleon was forty-two when his son was born. His work habits and his demeanour, at least at court, began to change with the arrival of a new family in his life. His routine was not as intensive as it had been at the beginning of his reign, and more time was spent socializing at hunts, dinners and balls. He started turning up late to the meetings of the Council of State. He even seems to have lingered longer at table, encouraged by Marie-Louise who was fond of food. Roederer remarked on it and commented, ‘General, you have become less expeditious [

expeditif

] at table,’ to which the Emperor cleverly replied, ‘It is already the corruption of power.’

130

Physically he was starting to undergo a transformation that has often been remarked upon. His was no longer the slim figure that had conquered Italy and Egypt. He had started to fill out and to develop a paunch. Some contemporaries believed it was a sign of decline.

131

Contact with Napoleon no longer automatically induced awe. On the contrary, some observers were disappointed by what they saw. Thus the writer Charles-Paul de Kock, in Paris in 1811, sneaked into the Tuileries Palace pretending to be part of an orchestra in order to catch a glimpse of him. He found Napoleon ‘yellow, obese, puffy, and his head pushed into his shoulders. I was expecting a God, I saw only a fat man.’

132