Citizen Emperor (75 page)

Authors: Philip Dwyer

Towards the Universal Monarchy

Would Napoleon then ever have been contented with his family, with living the life of a bourgeois monarch? To answer that question is to understand Napoleon, to fathom the vastness of his ambition, to get a glimpse of how others saw him, and what drove him to do what he did.

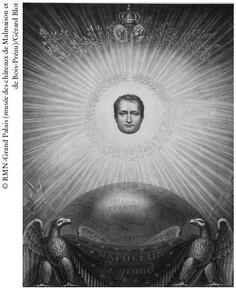

Antoine Aubert,

Napoléon le Grand

(Napoleon the Great), 1812. The caption reads: ‘Brilliant, immense star, he enlightens, he renders fruitful, and alone creates all the destinies of the world at will.’

In Napoleon’s time a number of terms were used interchangeably – ‘universal monarchy’, ‘universal empire’, ‘universal domination’, ‘world domination’, the empire of Rome or Charlemagne – to characterize his towering ambition. In the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, however, these terms were all expressions of a growing fear, relatively widespread, that Napoleon’s victories and his seemingly unlimited ambition would translate into something more than simple hegemony on the Continent. The term ‘universal empire’ was, moreover, almost always used pejoratively (as it generally had been since the sixteenth century).

133

In 1802, the Russian ambassador to Paris reported that Napoleon had spoken to him about proclaiming the ‘empire of the Gauls’.

134

Indeed, Russian statesmen drew a comparison between France and the Roman Empire and the wars that led other states to be either annihilated or made into allies or vassal states. ‘Europe’, warned the Russian chancellor, Vorontsov, in 1803, ‘has always been considered a republic or large society in which perhaps three or four [powers] had influence, but never one master.’

135

Europe’s political elite suspected Napoleon of harbouring ambitions to create a universal monarchy. The Prussian king, Frederick William III, spoke of his ‘inordinate ambition’ (

ambition démesurée

), while the Prussian ambassador to Paris, Girolamo Lucchesini, believed that Napoleon was going to ‘recreate Charlemagne’.

136

The Prussian foreign minister Karl August von Hardenberg, writing to Metternich in 1804, thought that that ‘fool’ Napoleon was ‘aiming for world domination; he wishes to accustom us all to regard ourselves as his subjects who must accommodate his every whim’.

137

Russia’s political elite was also under the impression that Napoleon was attempting to create a universal monarchy. They devised a number of measures to counter the possibility.

138

Alexander I’s Polish adviser Prince Adam Czartoryski believed that the proclamation of the Empire brought Napoleon a step closer to the idea of ‘universal domination’, and came to understand that the adoption of the imperial title in 1804 made him think he might be able to realize the ‘old dream of universal monarchy’.

139

Napoleon’s assumption of the throne of the newly created Kingdom of Italy in May 1805, and his annexation of the Republic of Genoa the following month, was grist for the mill and reinforced the belief that he was aspiring to a ‘

monarchie universelle

’.

140

The impression grew with every Napoleonic victory.

Two other developments reinforced the notion. The first was the annexation of Holland and the Papal States into the Empire in 1810. Rumours about the proclamation of a universal monarchy had been circulating for weeks. When Armand de Caulaincourt confronted Napoleon on the matter, his response was appropriately enigmatic: ‘This business is a dream, and I am wide awake.’

141

Second, when Napoleon invaded Russia in 1812, rumours were rife that once he had dealt with Alexander, he would march on Constantinople, China or India and deal a blow to the British. ‘There is talk of going to India,’ wrote Boniface de Castellane on 5 October 1812. ‘We have such confidence that we do not even think about whether such an enterprise might be successful, but only about the number of months’ march that would be necessary and the time it would take letters to come from France.’

142

The suggestion is, of course, that he would set out from Moscow not only to deal a blow to Britain, but also to conquer the East. One French historian recently gave the claim a fillip when he asserted that coronation gear was found in the French baggage train during the retreat from Moscow and concludes, somewhat speculatively, that Napoleon had moved from the idea of a ‘universal republic’ towards that of a ‘universal empire’ and that, after defeating Russia, he planned to have himself crowned in the Kremlin.

143

There are a number of occasions when Napoleon is supposed to have asserted that his goal was to rule the world. Miot de Mélito reported a conversation between Napoleon and his brother Joseph during the Consulate in which the First Consul asserted that they would be masters of the world within two years.

144

That was in July 1800. There is the noted quip in a letter from Napoleon to Vice-Admiral Latouche-Tréville concerning the plans to invade England in 1804: ‘Let us be masters of the straits for six hours and we shall be masters of the world.’

145

On one occasion, he is supposed to have said to his notorious minister of police, Joseph Fouché, ‘I must make all the people of Europe one people, and Paris the capital of the world.’

146

Again, he reportedly said to Fouché shortly before leaving for the Russian campaign, ‘How can I help it if a surfeit of power draws me towards dictatorship of the world?’

147

Even if Fouché is to be believed, one can easily dismiss much of what Napoleon said as hyperbole. Nevertheless, the rhetoric was there often enough for those in his entourage to suspect him of wanting to dominate or unite, depending on one’s point of view, all of Europe. He declared to the Austrian General Vincent, on 22 July 1806, that he would not be able to take the title ‘Emperor of the West’ until he had defeated a fourth coalition.

148

In 1811, he told the French diplomat Dominique Dufour de Pradt, ‘In five years, I will be master of the world. Only Russia is left, and I will crush it.’

149

That same year he said to the Bavarian General Wrede, ‘In three years I will be master of the universe.’

150

After his return from Elba, in April 1815, he admitted in a conversation with the political theorist Benjamin Constant that he had ‘wanted to rule the world’, and that in order to do it he needed ‘unlimited power . . . The world begged me to govern it; sovereigns and nations vied with one another in throwing themselves under my sceptre.’

151

Now

that

is hubris. The idea of a universal monarchy was given further impetus on St Helena. One of the evangelists of the Napoleonic cult, Emmanuel de Las Cases, who perpetuated Napoleon’s heroic identity through the publication of the

Memorial of St Helena

, noted the fallen Emperor’s utterances throughout his stay on the island. According to his view, Napoleon tamed the Revolution and marched at its head in a struggle to the death against Europe. In the process he became, in some respects, a universal monarch.

152

That is not much to go on, and some of these assertions have to be treated with a degree of scepticism. Napoleon was in the habit of waxing lyrical, of indulging in exaggeration, of sounding out ideas by expressing them in front of an audience. He may not have taken his own musings on world domination seriously. Moreover, he was heard denying that he had any such ambitions. Well, sort of. In an interview with the papal nuncio to Russia, Monsignor d’Arezzo, in Berlin in November 1806, he complained of the nuncio at Vienna, who had supposedly put it about that Napoleon wanted to make himself ‘Emperor of the West’. ‘I have never had that idea,’ he insisted, although he could not help but add, ‘I won’t say that it will never happen, but I wasn’t thinking about it at the time.’

153

Finally, none of the comments is first hand; all are reported snippets from conversations with Napoleon, some from people who cannot be entirely trusted. Fouché, for example, was intent on portraying himself in a positive light and his former master in a negative one when he wrote his memoirs many years after these conversations took place.

These statements are useful not so much for their accuracy as for the impression they give of what others believed Napoleon’s intentions to be, or believed him to be capable of. There is no doubt that Napoleon and the French had hegemonic pretensions on the Continent, but the question that intrigues and is more difficult to answer is whether it went beyond that. There is enough evidence to indicate that Napoleon was pushing the boundaries, seeing how far he could actually go, seeing how much he could emulate Alexander the Great, by at least contemplating, if not pursuing (and in a very haphazard fashion), the extension of French power outside Europe. In his mind, he was the tool of destiny; he felt he was driven towards a goal that he did not know, but that it involved changing the face of the world.

154

And only once his task was finished would all come to an end, as he imagined it, through a fever, a fall from a horse during the hunt, or a cannon ball. Until that time, ‘all human effort against me is but naught’.

155

Where does that leave Napoleon’s so-called aspirations for universal monarchy? Two points have to be kept in mind. The first is that Napoleon was a schemer, a dreamer who considered all his options before finally committing to the most practical though not always most ‘realistic’ plan (think of the Egyptian or Russian expeditions). The second point to keep in mind is that, as some historians have convincingly maintained, his foreign policy was continually renewed and dictated entirely by circumstances and their immediate needs.

156

Napoleon had in fact no coherent imperial foreign policy. Some historians have insisted that he conquered for the sake of conquering, with no defining goals and no overriding, consistent or specific long-term strategic objectives.

157

Since each campaign created new enemies, the wars were continuous and could stop only with the defeat of Napoleon. If he were truly intent on constructing a universal monarchy, then he never did so in any systematic way. Otherwise, he would have incorporated into the Empire most of Germany, including Prussia, defeated in 1806, and he would either have incorporated or partitioned the Habsburg Empire, defeated in four separate wars. Napoleon may have had an aggressive expansionist foreign policy, he may have wanted to dominate and control most of Europe, he may have fantasized about dominating the world’s colonial empires, but he could never become ‘Emperor of the Universe’.

17

Napoleon Reaches Out

Napoleon and Marie-Louise were inseparable for the first twenty-seven months, an experience he had not had with Josephine. The new marriage was, however, only a momentary reprieve from that ambition which gnawed at his soul like a canker. Members of his entourage noticed how much he had changed, notwithstanding the domestic happiness he was meant to be enjoying. He became preoccupied, and fell into periods of meditation, which were in fact a depression. The prefect Prosper de Barante, who was able to observe Napoleon closely during this period, noticed that ‘these thoughts were troubling him; his nights were ruined by long periods of insomnia; he would spend hours on a sofa, given over to reflection. Finally he would succumb and fall into a fitful sleep.’

1

He had plenty to worry about. Things had not gone as smoothly in Spain as he had expected, the Germans were groaning under the weight of occupation and exploitation, and the French were desperate for peace. Change, however, was in the nature of the beast. Napoleon was as incapable of resting on his laurels as Alexander the Great had been. Not content with having drawn his own dynasty closer to the established monarchies of Europe, he was now intent on a radical overhaul of the Empire, centred on his person and the consolidation of his power.