Citizen Emperor (90 page)

Authors: Philip Dwyer

As the ‘procession’ – the name that the survivors gave to the retreating army passing along the main road

76

– continued, acts of brutality and egoism increased as discipline declined. Men who lay down on the road were stripped bare or searched for valuables before they had even expired.

77

One veteran remarked that the route and the places where they bivouacked looked like the aftermath of a field of battle, with bodies, horses and equipment strewn everywhere.

78

Reports of cannibalism are more difficult to verify.

79

They usually involve Russian prisoners who had to resort to this extreme because they were given nothing to eat, and sometimes to behaviour among non-French survivors of the Grande Armée.

80

There are no references to French survivors resorting to cannibalism, which does not mean that French troops did not practise it, but that they did not admit to it, preferring to portray themselves as a little more civilized than the mass of humanity that made up the residue of the Grande Armée. There were reports, even more difficult to verify, of autophagy or self-mutilation in order to eat.

81

Convoys of food and mail reached the retreating army on 3 and 4 December, but although this was no doubt of some help, it could not prevent the continued disintegration. Fights broke out and murder was committed over food and shelter.

82

The men were essentially left to fend for themselves. A few lucky infantry regiments followed either cavalry or artillery regiments as best they could in order to feed off the dead and dying horses they left behind each morning. Stragglers formed into groups that attempted to stay ahead of the main army in order better to plunder the few standing villages along the way or to steal horses and valuables from encampments during the night.

83

Stealing in order to survive was not all that uncommon.

84

After a while, one could tell exactly when a man was going to fall and die: he would begin to totter, then walk as though drunk, then fall. A few drops of blood might trickle from the nose, and then the limbs would go stiff.

85

‘I noticed three men around a dead horse,’ remembered Sergeant Bourgogne:

two of the men were standing and appeared drunk, they were reeling so much. The third, who was a German, lay on the horse. The poor wretch, dying of hunger and unable to cut into it, was trying to bite it. He ended up dying in that position of cold and hunger. The other two, Hussars, had their mouths and hands covered in blood. We spoke to them but were unable to obtain any response; they looked at us laughing in a frightening manner and, holding on to each other, they sat next to the man who had just died where, probably, they ended up falling into a fatal sleep.

86

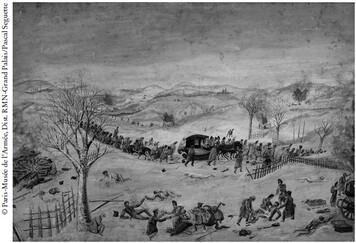

Attributed to Francois Fournier-Sarloveze,

Coup d’oeil de la route de Moscou depuis la Bérézina jusqu’au Niémen, 1812

(A look at the route from Moscow from the Berezina to the Niemen, 1812), around 1812.

There were nevertheless isolated acts of heroism in all of this, men going out of their way to save comrades and friends, and sometimes strangers, but increasingly they became the exception to the rule.

87

Napoleon Decamps

Not everybody blamed Napoleon for this catastrophe. His aura was so great that many officers, no matter what their nationality, believed that as long as he was with the army everything would be all right.

88

Napoleon himself realized that if the army did not get at least one week’s rest at Vilnius, then it was doomed. Serious too were the political consequences of the disintegration of the army. Reports were coming out of Petersburg about the French being defeated, so Napoleon had to act to counter these rumours. He did so in his usual fashion, by exaggerating the achievement at the Berezina. He ordered one of Berthier’s aides-de-camp, Anatole de Montesquiou, to travel to Paris with a report stating that over 6,000 prisoners had been taken. Along the way, he was to stop in major towns and spread the news.

This was nothing less than damage control. The most Napoleon could count on was around 40,000 men, all that remained of the once impressive Grande Armée, although there were another 20,000 fresh troops garrisoned at Vilnius. With these men, rested and under competent command, it was reasonable to expect them to hold Vilnius. One should not forget, moreover, that the Russian army was suffering as much from the hardships brought by the cold as the soldiers of the Grande Armée.

89

And once Napoleon had slipped through Kutuzov’s fingers at the Berezina, Kutuzov was not inclined to push the pace in pursuit of Napoleon. At this stage, the Russians were hardly in a position to mount a determined attack against Vilnius. If, on the other hand, Napoleon could not hold Vilnius, there was nothing to stop the Russians from moving into Poland and Prussia.

The 29th Bulletin was written on 3 December from Molodechno, about seventy-two kilometres south-east of Vilnius. It blamed the weather for the condition of the army, without however mentioning the horrendous losses it had suffered, except for the horses. It was easy enough for people to read between the lines. Despite mentioning the ‘victory’ at the Berezina, it would have been clear to all that this was a defeat. One hundred and sixty-four days had gone by since the army crossed the Niemen. About a day’s march out of Vilnius, on 5 December, at a small country house outside Smorgonie, Napoleon called his commanders together and told them of his decision to leave for Paris. The fact that he had, once again, almost been captured by Cossacks on the night of 3 December no doubt contributed to his decision to leave. All Russian corps commanders had received the order to try and capture Napoleon, along with a description of him : ‘thick waist, hair black, short and flat, strong black beard, shaved to the top of the ear, eyebrows very arched, but deep into the nose, a passionate but irascible look, aquiline nose with continuous traces of tobacco, the chin very prominent’.

90

A hardly flattering but nevertheless reasonably accurate portrait.

Under the circumstances, Napoleon’s entourage considered his immediate return to Paris the correct decision to make. This, the Emperor believed, would allow him to keep in line his unreliable German allies, Prussia and Austria, and raise a new army while in France. He was, as we shall see, able to recruit the soldiers, but the assumption that he could keep a firm grasp over Austria and Prussia was mistaken, and the repercussions of his departure on the morale and discipline of the army were much worse than he could have anticipated. The Malet affair may also have played on his mind. He had, after all, been away from the imperial capital for over seven months. His returning home now, comparable in some respects to what had happened in Egypt thirteen years previously – though then he had left the army in a somewhat better condition – may also have been about giving the impression of taking the initiative.

91

‘I am leaving you,’ he declared to the army, ‘but it is to find three hundred thousand soldiers.’

92

It was a political decision, possibly an apt one at the time, but one that was going to have devastating consequences for the remainder of the Grande Armée. There is no doubt they would have been better served by Napoleon’s continued presence.

Napoleon left with a few confidants – Caulaincourt and Duroc among others – on the evening of 5 December in three carriages escorted by a squadron of chasseurs and a squadron of Polish Light Horse of the Old Guard. Officers who still had horses were selected to make up a ‘sacred squadron’ (

escadron sacrée

) to accompany the Emperor, but the horses were so wretched and the officers so hungry it was dissolved after a few days.

93

Berthier begged, tearfully, to be taken with him but the request was declined.

94

Napoleon travelled incognito, as Caulaincourt’s secretary, Reyneval. Most senior officers understood his departure as a political decision, even though many in the lower ranks reproached him and a few insults were heard.

95

As to whether it was accepted by the army, reports vary. Some maintained that very few people openly criticized Napoleon’s decision to abandon them to return to Paris.

96

Before he left, however, he consulted with his marshals and generals about who should replace him as commander-in-chief. There were two possibilities: his brother-in-law Murat, or his stepson Eugène. Neither of them was really up to the job militarily – Davout or Ney would have been a better choice – but Napoleon believed that only a member of the imperial family would be able to keep at bay the petty feuding and jealousies bound to spring up between his marshals and generals once he had gone.

97

Besides, Murat was a king and outranked the other marshals. At least that was his reasoning, but he should have known better. The appointment of Joseph as commander-in-chief in Spain certainly had not stopped the bickering between Napoleon’s generals. Since Murat was a king and Eugène only a prince, the mantle fell on to Murat’s shoulders.

98

It was a mistake. Almost as soon as Napoleon had left, his marshals were at each other’s throats. Philippe de Ségur recalled, albeit with a good deal of hindsight, the misgivings he felt over Murat’s appointment: ‘In the empty space left by his [Napoleon’s] departure, Murat was hardly visible. We realized then – and only too well – that a great man cannot be replaced.’

99

Part of the problem was that the marshals were far too proud to take orders from one of their own, and Napoleon had made sure that he was surrounded by able lieutenants, not leaders.

100

On 8 December, Berthier wrote to say that the army was in complete disarray.

101

Murat had been unable to impose his views on those under his command so that the councils of war, which he was supposed to chair, often ended up as shouting matches.

102

Moreover, he demonstrated an extraordinary lethargy by failing to respond to letters from commanders in the field, thereby creating a leadership vacuum. He had, in fact, fallen into a deep funk, and asked permission of Napoleon to leave.

103

Napoleon forbade him to do so. Murat then raged against his brother-in-law, at one point calling him ‘mad’ (

insensé

), although he was supposedly put in his place by Davout for having done so.

104

No longer able to continue in the role, Murat summoned Eugène to his headquarters in Poznan´ . He claimed that he was ill, and that as a result he was leaving the army and going back to Italy where he was going to negotiate with Austria and Britain to keep his throne. In effect, he was abandoning his command and was asking Eugène to take over. It was not yet every man for himself in the face of a crumbling empire, but some of the rats were deserting the imperial ship. On 18 January 1813, Berthier followed Murat, as did most of the marshals, leaving Eugène no choice but to take over. After Murat’s departure, Eugène took stock of the situation. Murat ‘has left me this great mess’, he complained to his wife.

105

Napoleon’s response to Murat was cutting: ‘You are a good soldier on the battlefield, but off it, you have neither vigour nor character.’

106

Even Napoleon admitted he had made a mistake in appointing Murat.

107

Eugène’s appointment was greeted with great relief in the army.

108

It would not have been until he wrote to Napoleon towards the end of January, after Murat had left the army, that the Emperor received a clearer picture of what was going on.

109