Citizen Emperor (94 page)

Authors: Philip Dwyer

The king’s appeal met with a limited popular response: 1,400 men joined the Hanseatic Legion as infantry and another 200 as cavalry in the first days of liberation, often supplying their own equipment, although arms were also eventually supplied by Britain. The numbers increased in the following weeks, so that by April 1813 over 3,600 men had enlisted. Moreover, in what appears to be a German variant of the French National Guard, more than 6,000 men between the ages of eighteen and forty-five joined the Citizens’ Militia (

Bürgergarde

), equipped by a re-established Senate in Hamburg. It has to be said, however, that even if the Citizens’ Militia represented a break in Hamburg’s political culture, it does not seem to have been taken very seriously by the people of Hamburg; few followed training with the dedication that was expected of them.

51

Poorly led, badly trained and badly equipped, they would be no match for regular soldiers once the French returned.

Similar scenes were played out in Berlin, although an appeal to patriotic sentiment was probably unnecessary.

52

Prussian conscription was able to tap into proportionately higher numbers of troops than any other great power – 6 per cent of the population was under arms.

53

(In comparison, the French were conscripting in 1813 about 2.1 per cent of the population, and that was the highest it ever reached for the revolutionary and Napoleonic eras, about the same percentage of men mobilized during the wars of Louis XIV.) The Landwehr units on the other hand were poorly trained and poorly equipped, often lacking in the rudiments of uniforms, shoes and weapons. About 30,000 men volunteered to serve against France, representing about 10 per cent of the overall number of Prussian effectives.

54

Compared to the French

levée en masse

in 1792, this was not a particularly impressive turnout and says a great deal about the structure of Prussian-German society. As for the Free Corps (

Freikorps

) units commanded by Baron Ludwig Adolf Wilhelm von Lützow, they were authorized immediately after the declaration of war by Frederick William in an attempt to recruit young men outside Prussia. By the middle of 1813, they had managed to attract only 3,891, almost half of whom were Prussian.

55

The sentiments expressed by this small but highly articulate group of men came to define latterday German patriotism. The poet Theodor Körner, for example, whose death in August 1813 and whose writings came to symbolize the patriotism of German middle-class youth, spoke about the ‘self-willed heroism of a natural elite, whose sacrifice would inspire God to save the nation’.

56

Certainly, ‘patriotism’, defined as a love of one’s (sometimes adopted) country, was beginning to take hold among people in central Europe at the beginning of the nineteenth century, but it needs to be remembered that the vast majority of troops fighting in the so-called Wars of Liberation were conscripts, among whom few such sentiments could be found. Patriotism as it later came to be defined by nineteenth-century German historians was not to play a decisive role in the coming wars, even if it was present in an incipient form among some of the volunteers.

57

The types of patriotic propaganda that were likely to be most influential were regional rather than national, and the motive inspiring these men was more likely to be revenge or even religion than anything else.

58

Women also played an important role in mobilizing civil society in Germany for war, encouraging men to enrol, sometimes chastising them for a lack of patriotic fervour, donating time and money to form associations throughout the German-speaking lands, meeting to knit socks and stockings, make shirts and bandages, sewing flags, donating money and jewellery and sometimes publishing patriotic pamphlets, poems and songs.

59

A true measure of ‘patriotism’ was people’s readiness to donate hard cash. In Hamburg, female domestic servants donated over 10,000 marks to help fit out the Hanseatic Legion.

60

In the Austrian Empire, women’s associations met to organize war relief and medical care.

61

Metternich’s daughter Marie, along with other ‘patriots’, made dressings for the wounded out of old linen sheets (despite the fact that Austria was still meant to be an ally of France).

62

But there was not the same desire to go to war in Austria in July 1813 as there had been in 1809. On the contrary, despite the general revulsion against Napoleon’s conquests, and despite the importance of anti-Napoleonic propaganda, Austrians believed his powers to be so extraordinary that any undertaking against him would be pointless.

63

This was not the case in Prussia, where there was an intensive propaganda campaign to promote valour and (in a number of pamphlets) ‘manly’ virtues that encouraged a warlike spirit against France among men and women. The rigours of occupation and the consequent hardships associated with economic decline fuelled the desire to be rid of the French. At the centre of this effort was the notion that to die for the fatherland was the greatest honour.

64

There were also instances of cross-dressing in which women, wearing men’s uniforms, would fight alongside men. Some of the more notable examples were Eleonore Prochaska and Anna Lühring who fought with the Lützow Freikorps, even after their gender was discovered.

65

Lühring was the first woman to receive the Iron Cross (even though she was not Prussian).

The Beast of the Apocalypse

It is worth dwelling on the type of imagery used to demonize Napoleon in a bid to galvanize the peoples of Europe.

66

Much of that imagery was religious in nature as were, one could argue, the wars against France.

67

There was a good deal of vitriol, both written and oral, directed against Napoleon by the conquered peoples of Europe, which began to find an outlet in the media of the day only after 1812. It was common enough to portray Napoleon as a bloodthirsty tyrant, ‘the enemy of the human race’, well before that time.

68

To depict him as ‘tyrant’ is also to underline the illegitimacy, the evilness, of his reign. It was the first stage in portraying him as Antichrist. Satan, Lucifer, the Great Horned Serpent or the Devil was an image that flourished not only in most parts of Europe, but as far afield as the United States and Guatemala, regardless of religious affiliations. It appears to have been part of the millenarian movement at the end of the eighteenth century.

69

The description may have had its origins in the innumerable odes, sermons, poems and pamphlets that looked upon the struggle with Napoleon and France as a struggle between good and evil, between the powers of light and darkness.

70

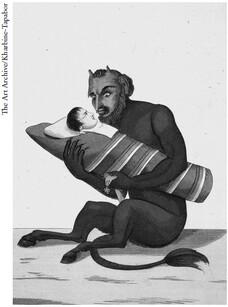

Anonymous,

Le petit homme rouge berçant son fils

(The little red man rocking his son), no date but probably 1813–15. A varation on a theme. Instead of the Virgin Mary nursing the infant Jesus, we see a proud devil nursing a baby Napoleon, born in hell. The swaddling is bound with tricolour ribbon, while the devil is holding the Legion of Honour. The caption reads, ‘Here is my beloved son, who has given me so much satisfaction,’ a quotation from St Mark. Variations of this caricature appeared in Germany in 1813 and 1814.

The onslaught of atheist republican governments against the Catholic Church, in France and abroad, did not do anything to appease the anti-Catholic Francophobia that dominated much of the British pamphlet and broadside literature of the day. On the contrary, there had been a tendency to displace the popular association of the Antichrist with Rome on to republican France.

71

It did not take much of a leap, once this pattern had been established, to project the image of the Antichrist on to Napoleon. One prolific British pamphleteer, Lewis Mayer, counted the number of emperors, popes and heads of state ‘alluded to by the horns of St John’s first Beast, Rev. 13’ and came to the conclusion that there had to date been 665 – Napoleon was the 666th.

72

The British, in short, sought to identify Napoleon, or at least Napoleonic France, with the Beast of the Book of Revelation. All references to ‘the angel of the bottomless pit, the king of the locusts, the beast with two horns and the head of the Antichristian powers’ were specific biblical allusions to Napoleon. Another millenarian and friend of Samuel Johnson, Hester Lynch Thrale, collected contemporary English anecdotes that led her to conclude the French Revolution had been the harbinger of Napoleon as Antichrist, noting that some women in Wales had told her that his titles added up to 666. Napoleon’s conquest of Rome and his arrest of the pope led some British millenarians to conclude that he was the instrument of a Jewish Restoration that would bring on the Christian millennium.

73

Napoleon or ‘Boney’ was also demonized in popular culture so that nursery rhymes were used to scare children into submission (that continued for a good part of the nineteenth century).

Baby, baby, naughty baby,

Hush! you squalling thing, I say;

Peace this instant! Peace! or maybe

Bonaparte will pass this way.

Baby, baby, he’s a giant,

Black and tall as Rouen’s steeple,

Sups and dines and lives reliant

Every day on naughty people.

Baby, baby, if he hears you

As he gallops past the house,

Limb from limb at once he’ll tear you

Just as pussy tears a mouse.

And he’ll beat you, beat you, beat you,

And he’ll beat you all to pap:

And he’ll eat you, eat you, eat you,

Gobble you, gobble you, snap! snap! snap!

74

In Russia, Napoleon was referred to in the press during the War of the Third Coalition as ‘the son of Satan’ or the ‘abominable hypocrite’.

75

Alexander called on the Orthodox Church to assist him in the struggle against France.

76

In response the Holy Synod first explained to the faithful the cosmological significance of the struggle against Napoleon: he had taken part in the idolatrous festivals of the French Revolution; he had preached Islam in Egypt; he had restored the Jewish Sanhedrin (a reference to Napoleon calling an assembly of rabbis and Jewish laymen in 1807 to discuss the means of better assimilating Jews); and now he was bent on overthrowing Christianity – with the help of the Jews – and of declaring himself the Messiah. Notable is the Synod’s appeal to anti-Semitism in garnering popular support for their campaign. The Synod went on to describe Napoleon as the Antichrist, something that was then accepted by the Russian peasantry as a truism.

77

In the wake of Tilsit, both the state and the Church were subsequently put in the somewhat difficult position of explaining to the Russian people why the Tsar had signed a treaty with the devil. A rumour doing the rounds in Russian villages claimed that Alexander met Napoleon in the middle of a river in order to wash away his sins.

78

The Synod’s initial proclamation condemning Napoleon was banned, as were any sermons based on it, but it had become obvious to those who took scripture a little too literally that if Napoleon was the Antichrist and he had defeated Alexander, then Russia’s defeat would usher in the new millennium. Tilsit was interpreted in just that way. The anti-Napoleonic trend in the Russian press continued despite the Treaty of Tilsit and despite Erfurt, so that when war broke out in 1812 Napoleon was already considered the Antichrist by many if not most Russians.

79

The thing that sets the Russian literature apart from its European equivalents is that the Tsar was portrayed as the tool of God, chosen to defeat Napoleon.

80

The more inevitable an invasion came to appear, the more Napoleon was associated with the Antichrist. He was variously referred to in contemporary Russian texts as the ‘false Messiah’, the ‘Gallic Beast’ and the ‘son of Satan’.

81

(In contrast, and from about 1813 on, Alexander became a divine figure and was closely associated in Russia with the ‘divine victory’ over Napoleon.)

82

The educated inhabitants of Moscow had a more nuanced view of Napoleon tinged with a mixture of awe and curiosity.

83

The vast majority of Russian peasants, on the other hand, perceived the struggle against Napoleon and the French in religious terms that were deeply rooted in the past.

84