Clinical Handbook of Mindfulness (111 page)

Read Clinical Handbook of Mindfulness Online

Authors: Fabrizio Didonna,Jon Kabat-Zinn

Tags: #Science, #Physics, #Crystallography, #Chemistry, #Inorganic

ogy Nursing Forum, 34

(5), 1059–1066.

Monti, D. A., Peterson, C., Kunkel, E. J., Hauck, W. W., Pequignot, E., Rhodes, L., et al.

(2006). A randomized, controlled trial of mindfulness-based art therapy (MBAT) for

women with cancer.

Psycho-oncology, 15

(5), 363–373.

Moscoso, M., Reheiser, E. C., & Hann, D. (2004). Effects of a brief mindfulness-based

stress reduction intervention on cancer patients.

Psycho-oncology, 13

, S12.

Murray, S. A., Kendall, M., Boyd, K., Worth, A., & Benton, T. F. (2004). Exploring

the spiritual needs of people dying of lung cancer or heart failure: A prospective

qualitative interview study of patients and their carers.

Palliative Medicine, 18

, 39–

45.

National Cancer Institute of Canada. (2007).

Canadian cancer statistics

. Canadian

Cancer Society.

Norman, G. R., Sloan, J. A., Wyrwich, K. W., & Norman, G. R. (2003). Interpretation

of changes in health-related quality of life: The remarkable universality of half a

standard deviation.

Medical Care, 41

, 582–592.

Northouse, L. L., Laten, D., & Reddy, P. (1995). Adjustment of women and their hus-

bands to recurrent breast cancer.

Research in Nursing and Health, 18

, 515–524.

Chapter 20 Mindfulness-Based Interventions in Oncology

403

Ott, M. J., Norris, R. L., & Bauer-Wu, S. M. (2006). Mindfulness meditation for oncology

patients.

Integrative Cancer Therapies, 5

, 98–108.

Peterman, A. H., Fitchett, G., Brady, M. J., Hernandez, L., & Cella, D. (2002). Measuring

spiritual well-being in people with cancer: The functional assessment of chronic ill-

ness therapy–spiritual well-being scale (FACIT-sp).

Annals of Behavioral Medicine:

A Publication of the Society of Behavioral Medicine, 24

(1), 49–58.

Pitceathly, C., & Maguire, P. (2003). The psychological impact of cancer on patients’

partners and other key relatives: A review.

European Journal of Cancer, 39

(11),

1517–1524.

Ries, L. A. G., Melbert, D., Krapcho, M., Mariotto, A., Miller, B. A., Feuer, E. J., et al.

(2007).

SEER cancer statistics review, 1975–2004

. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer

Institute.

Roscoe, J. A., Morrow, G. R., Hickok, J. T., Bushunow, P., Matteson, S., Rakita, D., et al.

(2002). Temporal interrelationships among fatigue, circadian rhythm and depres-

sion in breast cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy treatment.

Supportive

Care in Cancer, 10

, 329–336.

Savard, J., & Morin, C. M. (2001). Insomnia in the context of cancer: A review of a

neglected problem.

Journal of clinical oncology: Official journal of the American

Society of Clinical Oncology, 19

, 895–908.

Saxe, G. A., Hebert, J. R., Carmody, J. F., Kabat-Zinn, J., Rosenzweig, P. H., Jarzobski,

D., et al. (2001). Can diet in conjunction with stress reduction affect the rate of

increase in prostate specific antigen after biochemical recurrence of prostate can-

cer?

Journal of Urology, 166

, 2202–2207.

Sephton, S. E., Sapolsky, R. M., Kraemer, H. C., & Spiegel, D. (2000). Diurnal cortisol

rhythm as a predictor of breast cancer survival.

Journal of the National Cancer

Institute, 92

(12), 994–1000.

Shapiro, S. L. (2001). Quality of life and breast cancer: Relationship to psychosocial

variables.

Journal of Clinical Psychology, 57

, 501–519.

Shapiro, S. L., Bootzin, R. R., Figueredo, A. J., Lopez, A. M., & Schwartz, G. E. (2003).

The efficacy of mindfulness-based stress reduction in the treatment of sleep distur-

bance in women with breast cancer: An exploratory study.

Journal of Psychoso-

matic Research, 54

, 85–91.

Smith, J. E., Richardson, J., Hoffman, C., & Pilkington, K. (2005). Mindfulness-based

stress reduction as supportive therapy in cancer care: Systematic review.

Journal

of Advanced Nursing, 52

, 315–327.

Speca, M., Carlson, L. E., Goodey, E., & Angen, M. (2000). A randomized, wait-list con-

trolled clinical trial: The effect of a mindfulness meditation-based stress reduction

program on mood and symptoms of stress in cancer outpatients.

Psychosomatic

Medicien, 62

(5), 613–622.

Strain, J. J. (1998). Adjustment disorders. In J. F. Holland (Ed.),

Psycho-oncology

(pp. 509–517). New York: Oxford University Press.

Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) Program. (2007).

Prevalence

database: “US estimated complete prevalence counts on 1/1/2004”

National Can-

cer Institute.

Taylor, E. J. (2003). Spiritual needs of patients with cancer and family caregivers.

Cancer Nursing, 26

, 260–266.

The Trials of Hypertension Prevention Collaborative Research Group. (1997). Effects

of weight loss and sodium reduction intervention on blood pressure and hyperten-

sion incidence in overweight people with high normal blood pressure.

Archives of

Internal Medicine, 157

, 657–667.

Touitou, Y., Bogdan, A., Levi, F., Benavides, M., & Auzeby, A. (1996). Disruption of the

circadian patterns of serum cortisol in breast and ovarian cancer patients: Relation-

ships with tumour marker antigens.

British Journal of Cancer, 74

, 1248–1252.

404

L.E. Carlson et al.

van der Poel, H. G. (2004). Smart drugs in prostate cancer.

European Urology,

45

(1), 1–17.

van der Pompe, G., Antoni, M. H., & Heijnen, C. J. (1996). Elevated basal cortisol levels

and attenuated ACTH and cortisol responses to a behavioral challenge in women

with metastatic breast cancer.

Psychoneuroendocrinology, 21

, 361–374.

Van Wielingen, L. E., Carlson, L. E., & Campbell, T. S. (2006). Mindfulness-based stress

reduction and acute stress responses in women with cancer.,

15

S42.

Van Wielingen, L. E., Carlson, L. E., & Campbell, T. S. (2007). Mindfulness-based stress

reduction (MBSR), blood pressure, and psychological functioning in women with

cancer.

Psychosomatic Medicine, 69

(Meeting Abstracts), A43.

Walker, M. S., Zona, D. M., & Fisher, E. B. (2006). Depressive symptoms after lung

cancer surgery: Their relation to coping style and social support.

Psycho-oncology,

15

(8), 684–693.

World Health Organization. (2005).

WHO cancer control programme

.

Wua, J., Kraja, A. T., Oberman, A., Lewis, C. E., Ellison, R. C., & Arnett, D. K. (2005).

A summary of the effects of antihypertensive medications on measured blood pres-

sure.

American Journal of Hypertension, 18

, 935–942.

Zabora, J., BrintzenhofeSzoc, K., Curbow, B., Hooker, C., & Piantadosi, S. (2001). The

prevalence of psychological distress by cancer site.

Psycho-oncology, 10

(1), 19–28.

Part 4

Mindfulness-Based Interventions

for Specific Settings and Populations

21

Mindfulness-Based Intervention

in an Individual Clinical Setting:

What Difference Mindfulness

Makes Behind Closed Doors

Paul R. Fulton

I would like to beg you to have patience with everything unresolved

in your heart and try to love the questions themselves as if they

were locked rooms or books written in a very foreign language. Don’t

search for the answers, which could not be given to you now, because

you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything.

Live the questions now. Perhaps then, someday far in the future, you

will gradually, without even noticing it, live your way into the answer.

–

Rainer Maria Rilke (1875–1926), Letters to a Young Poet

Introduction

In my teens, when I began my study of Buddhist and Western clinical psychol-

ogy, few resources were available. Most published materials were general

and theoretical, such as Erich Fromm’s

Zen Buddhism and Psychoanal-

ysis

(Fromm, Suzuki, & DeMartino, 1960),

or Hubert Benoit’s (1955)

The

Supreme Doctrine

. There was no practical literature, and like many others,

I was left to explore the territory without a map. When a group of like-

minded individuals formed a study group in the early 1980s, the idea of the

integration of psychotherapy with meditation remained mildly disreputable.

Meditation was associated with New Age self-help and exotic spirituality, and

we lingered quietly at the margins of the mainstream.

In these early efforts to integrate these two disciplines, most of the influ-

ence of mindfulness was through the therapist’s own practice, remaining

unnamed and invisible to the patient, a potent but transparent background

to the encounter. However, with the growing popularity of mindfulness,

patients are more receptive to its use

(Psychotherapy Networker, 2007).

In my own practice it is common for people already interested or deeply

grounded in meditation to seek me out because of it. While it is relatively

rare for me to recommend meditation, if I feel it is appropriate, I now do so

without the squeamishness I felt early in my clinical career. The issue of how

one introduces meditation to patients has all but disappeared.

Mindfulness has gained respectability due to the recent explosion of

published literature, much of it providing empirical support of its clinical

407

408

Paul R. Fulton

efficacy. Excellent guidance is increasingly available to new generations of

clinicians. To make such research possible, the concept of mindfulness,

derived from Buddhist practice and literature, has required refinement and

definition. For meaningful clinical trials to be conducted, it has been neces-

sary to define consistent treatment conditions, to try to isolate the “active

ingredients” in mindfulness, and control for extraneous variables. Conse-

quently, much of the available literature focuses on protocol-driven use of

mindfulness, applied in a structured manner with well-defined populations.

What is determined to be effective in a protocol-driven research trial may

not translate naturally to the individual treatment setting. What actually hap-

pens in the face to face encounter between patient and therapist in the use

these concepts and techniques? This volume provides a number of responses

to this question. In this chapter I take up the issue through case examples,

from a first-person real world perspective, learned by doing, informed by

study and (periodically inconsistent) meditation practice of nearly 35 years,

to illustrate some relatively unformulaic ways mindfulness informs the treat-

ment process.

Please note that in this chapter, my use of the term “mindfulness” lacks

a certain precision, and is offered as a kind of abbreviation for a range of

practices, perspectives, or observations gained through mindfulness practice

and study that are broader than redirection of attention or mental training.

The Continuum

As I ended a day-long program teaching about mindfulness to mental health

professionals, an elderly psychiatrist and former colleague came up to me

and asked with genuine puzzlement, “So, what

is

a mindfulness-based inter-

vention?” I was embarrassed that the answer remained unclear. The problem,

I decided, is that for all the efforts to arrive at a consistent and concise defini-

tion of mindfulness, it remains elusive for the breadth of its application. In the

clinical setting, the concept of mindfulness quickly loses precision because

its influence can be seen at a variety of levels. Describing these levels pro-

vides a kind of map to locate what we mean when discussing mindfulness.

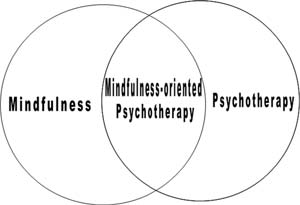

The intersection of mindfulness and psychotherapy can be described as

occurring along a continuum. One pole of this continuum might be called

the “implicit” end, where mindfulness is practiced by the therapist, but

is otherwise invisible to the patient. Elsewhere I have written about the

“implicit” end of the continuum, describing the contribution mindfulness

practice makes to the mind of the therapist, and through it, to the therapy

(2005). Mindfulness, I argued, helps the therapist to cultivate mental capac-

ities and qualities such as attention, affect tolerance, acceptance, empathy,

equanimity, tolerance of uncertainty, insight into narcissistic tendencies, and

perspective on the possibility of happiness. The degree to which the thera-

pist’s own mindfulness practice influences treatment outcome is just begin-

ning to receive empirical attention.

Moving along the continuum, the use of mindfulness becomes more

explicit, incorporating concepts informed by mindfulness, to psychother-

apy overtly incorporating specific mindfulness techniques. Some of the

stations along this continuum are described by

Germer (2005)

as a