Clinical Handbook of Mindfulness (112 page)

Read Clinical Handbook of Mindfulness Online

Authors: Fabrizio Didonna,Jon Kabat-Zinn

Tags: #Science, #Physics, #Crystallography, #Chemistry, #Inorganic

Chapter 21 Mindfulness-Based Interventions in an Individual Clinical Setting

409

mindfulness-practicing psychotherapist, mindfulness-informed psychother-

apy, and mindfulness-based psychotherapy. The explicit end of this contin-

uum, however, does not stop there, as many patients will take up meditation

per se, perhaps first as preparation to enable themselves to enter therapy, as

an adjunct to therapy, or as a parallel activity conducted as a spiritual practice

of awakening quite apart from the therapy’s original presenting problem.

Of course, no unidimensional continuum can adequately describe the

many ways psychotherapy and mindfulness come together in life, as the clin-

ical examples below attest. This chapter will focus on a variety of ways mind-

fulness practice informs what actually occurs in the individual clinical setting

at different levels of this implicit-explicit continuum.

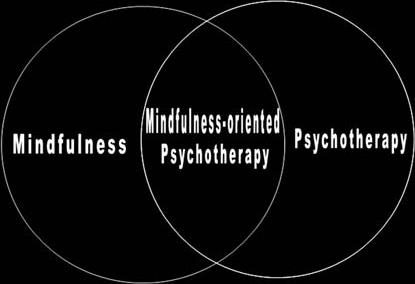

In addition to the continuum, we can also imagine a Venn diagram in

which the domains of psychotherapy and meditation are each described by

circles. While each has its own original purpose and range of effectiveness,

the circles overlap in mindfulness-oriented psychotherapy (Figure 21.1).

However, when the therapist is a meditator,

all

activities, whether the con-

duct of psychoanalysis, mindfulness-based cognitive therapy, or doing the

laundry, are all informed by mindfulness. This might be depicted by drawing

a third circle encompassing both of the other two (Figure 21.2).

Figure. 21.1.

Mindfulness-oriented psychotherapy as the area of overlap between

mindfulness and psychotherapy

Figure. 21.2.

Psychotherapy when the clinician practices mindfulness.

410

Paul R. Fulton

General Considerations

One begins to see the difficulty establishing distinctions about what constitutes

mindfulness-based psychotherapy. This integration may be most simple when

we craft techniques clearly inspired by mindfulness. For example, one can

teach exercises such as the “Three Minute Breathing Space,” (Segal, Williams,

& Teasdale,

2002),

visualizations conducive to acceptance

(Hahn, 1976;

Kabat-Zinn,

1994),

or prescribe techniques intended to use emotions as objects of mindfulness

(Brach, 2003).

But mindfulness is not reducible to a class of interventions or techniques, and

must be understood in a much broader context. It originates as the method-

ological cornerstone of a system of understanding, focused on the nature

of suffering and the nature of happiness. It is an understanding that, with

time and practice, we

become

. When practiced wholeheartedly, it becomes

inseparable from all we do, including our clinical work. It is manifest as

a quality of attention, a way to hold experience, a commitment to ethi-

cal conduct, and an understanding of a path to be traversed. The com-

mon denominator of all applications of mindfulness is the turning toward

experience; the common therapeutic factor is a changed relationship to

experience.

A fundamental contribution of mindfulness is its formulation of the nature

of suffering and its relief, which differs from the way distress is often formu-

lated in traditional clinical terms. In the medical model, suffering is regarded

as symptom of an underlying disorder, a developmental arrest, learned errors

in thought, perception, or conduct, or psychological injury. Treatment is

often based on identifying and treating the underlying disorder to relieve

the symptomatic distress. By contrast, the Buddhist formulation, upon which

mindfulness rests, holds that suffering is inevitable and arises due to a mis-

directed effort to manipulate our experience to our liking. That is, in our

actions large and imperceptibly small, we are constantly trying to hold on to

what is pleasurable, and rid ourselves of the unpleasant. In Buddhist terms

this is often described in shorthand as grasping. As most experience is tinged

by these valences, the effort to control is nearly ceaseless. In this respect, suf-

fering is universal, its operation identical irrespective of this or that putative

underlying disorder, or the particular conditions to which we react. It may

manifest in overt misery, or it may be extremely subtle in its expression as a

sense of unease or dissatisfaction, even in the face of abundance. Grasping is

also seen in a tendency to identify with our thoughts and mental construc-

tions, investing them with greater reality and durability than they possess.

Suffering arises when we cling to that which is unreliable for being changing

and ultimately empty. Understanding this formulation of suffering as originat-

ing in our effort to control or grasp offers an opportunity to radically reframe

the problem of our patients’ suffering.

Mindfulness and Its Influence on the Practice

of Psychotherapy

Inevitably, patients arrive with their own hypotheses, or in many cases, con-

victions, about what is wrong, what must be changed, lost, or gained before

Chapter 21 Mindfulness-Based Interventions in an Individual Clinical Setting

411

their distress can be lifted. Often the formulation is itself an obstacle. This is

illustrated by the case of Lydia.

A former therapist herself, Lydia came to treatment after her previous ther-

apist of 10 years moved away. She was recently divorced by her choice, and

was now working to rebuild her life and a career in her chosen field. For

years she was beset by the fear that she would be alone, left out, and iso-

lated, a fate she concluded was evidence that something was wrong with

her. Her previous therapies had focused on identifying and fixing what was

wrong, but she still was susceptible to downward spirals of self doubt and

despair, driven by her harsh self inquiry conducted with the emotional tone

of an inquisition. When I asked if she had established what was wrong with

her, she said she had not; her previous therapy had yet to get to the bottom

of it. I asked what she really wanted, and she was clear that it was to be

happier. When I asked how it felt when she tried to analyze her problems,

she said she felt truly terrible. I suggested that given that her desire was to

be happy, and this inquiry made her miserable, had she considered setting

it aside? Lydia was appalled. After all, this picking away at her wounds was

the only method she could imagine, and she believed (against all evidence)

that it was the lifeline that would ultimately be her rescue. I suggested that in

light of her experience to date, the next time she noticed she was engaged

in this spiral, she consider how she felt, and if so inclined, stop as best she

could, redirect her attention, and see how she felt as a result. She was threat-

ened by this idea, and the next several sessions were given to understanding

the nature of her doubt. Some of this doubt came from her own early profes-

sional training in analytic psychotherapy. Lydia conceded that her efforts had

been counterproductive, and she might consider an alternative. This experi-

ment became the shared working formulation between us, and she was able

to notice when she started down this steep and painful slope, and arrest her

fall. Together we began to apply the same approach to other facets of her life,

and she became more adept at identifying mental habits relatively quickly

after appearing in experience, and exercise a choice in how to proceed. For

example, when she found herself grumbling about having to file a stack of

papers, she noticed her irritability, and spontaneously saw how it was not

the filing itself, but her mind, that was causing her torment. She remained

introspective, but what she sought to understand shifted away from the diag-

nosis of a deficit and toward consideration of the impact of her current men-

tal activity on her sense of well-being. The issue of whether redirecting her

attention constituted an abandonment of some truth-seeking became irrele-

vant; she was freeing herself, and that was rewarding enough.

There are several elements of this reframe that owe a debt to mindfulness.

The first is that it offered an alternative to the vestigial impulse, inherent in

the medical model, to fix or rid oneself of something. Rather than analyz-

ing or interpreting the underlying meaning of distress, the focus shifted to a

pragmatic investigation of what brings relief and what brings more distress,

as judged with genuine open-mindedness. In the process, Lydia turned her

attention to her here-and-now experience, rather than invest her energy in

the unproductive rehearsal of familiar stories.

This touches on another element of formulations derived from mindful-

ness. That is, what we do is effectively being practiced and strengthened,

exactly as a pianist’s skills are honed by rehearsal. Conversely, what we cease

to do is gradually weakened, and perhaps ultimately extinguished. When we

412

Paul R. Fulton

point out to our patients that what they do (whether in thought, speech, or

action) is being practiced and strengthened, it offers a new basis to evaluate

the impact of those actions on their well-being.

This is illustrated by Andrew, a genuinely caring man who was concerned

over his tendency to become impatient or angry, which he took to be signs

of failure and moral weakness. In any angry encounter, he suffered both the

inherently unpleasant anger itself, as well as the self-judgment he leveled for

his loss of control. Even when he thought his anger was justified, he felt bad

and helpless to change his reactions. These angry events stuck with him. I

asked if he found relief in revisiting these episodes, or if they perpetuated

the feelings of anger and shame. Andrew said it made him feel worse. I intro-

duced the idea of practice as strengthening these pathways of anger and judg-

ment, and some neurophysiological evidence behind it (which appealed to

his scientific background). I pointed out the way that his lingering over the

offending event and his own reactions amounted to a sustained rehearsal.

Andrew understood, and immediately brightened at the idea that each new

episode offered an opportunity to relate to his anger differently, as a chance

to practice something different. I suggested that he practice directing his

attention to the subjective mental and physical experience of anger before

responding. In this way, he gradually became a student of his own experi-

ence and a trained observer of how his anger is triggered in real time. In

the process, he gained access a broader palate of responses. The emphasis

on practicing took his anger out of the domain of moral weakness, which

only tended to cause him to add fuel to his shame, and recast it as something

workable in the moment of its arising, something one

does

, rather than evi-

dence of a relatively immutable character flaw or statement about “what kind

of person” he was.

The role of practice and learning is not unique to mindfulness, of

course. What mindfulness contributes to this commonsense observation is

an expanded range of mental qualities that are amenable to simple cultiva-

tion. Qualities we often consider to be relatively fixed and trait-like, such as

generosity, compassion, anger, impatience, or even interest in our reactions,

are all legitimate subjects for on-the-job training. Such observations serve as

an antidote to the tendency to see ourselves as relatively static, and to define

ourselves in fixed, often uncharitable ways. They invite us to try to become

what we value in a practical way. In practice, attending to “what one does”

is more workable than fixating on “what one is.” The liberating benefit of

learning to limit our tendency to form and attach to any fixed perception of

ourselves is one benefit of a nuanced mindful understanding of our mental

activity.

Often, our patients’ habits of mind are harsh and self-punitive. This was

true of both Lydia and Andrew. I asked them to attend to the quality of their

minds when, for instance, Lydia engaged in her well-practiced self-analysis,