Clive Cussler; Craig Dirgo (34 page)

Read Clive Cussler; Craig Dirgo Online

Authors: The Sea Hunters II

Tags: #General, #Social Science, #Shipwrecks, #Transportation, #Ships & Shipbuilding, #Underwater Archaeology, #History, #Archaeology, #Military, #Naval

Given the accuracy of the fishermen’s positions, it seemed more expedient and less time-consuming to simply check out each individual hanger. Running search lanes was like looking for the proverbial needle in the haystack, one straw at a time. But now the stormy season was coming on. We would have to hang tough before making another effort.

Graham Jessup fitted out a new ship and headed for the

Titanic

site to bring up artifacts, but luckily, John Davis of ECO-NOVA, who had involved me in the

Sea Hunters

documentaries, offered to joint-venture the third

Carpathia

expedition. John would direct operations, as well as bring along a film crew to videotape the seafloor using a newer and larger ROV—with better capabilities—than the one used previously.

In December, during a lull in the weather and restocked with food, water, and fuel,

Ocean Venture,

with reliable Gary Goodyear at the helm, set out once again. During the voyage to the search area, the remaining seventeen snag positions provided by the fishermen were plotted into the ship’s computer. The plan was to start at the north end and zigzag down south, hitting the marked snags as they went

The first target was a mystery we still haven’t solved. The sonar readings showed what is most definitely a destroyer, with the aft hundred feet totally missing—almost as if a giant hand had sliced it off with a knife. The stem could not be found on either forward or sidescan sonar. The best guess is that the ship was torpedoed but did not sink right away. The stem pulled free and sank, but the rest of the ship floated long enough to be towed until it sank, too. There were no records of a warship going down in this area. Hopefully, someday we’ll be able to identify her.

The following days passed without a solid strike on which we could hang our hat. Operating twenty-four hours a day, the ship and crew began to show signs of frustration and fatigue. Still, anxiety ran high as

Ocean Venture

neared the seventeenth and last target in the extreme end of the southern search area.

Then, at last, the gods smiled, and the sonar reading began revealing what looked like a large ship on the bottom. Everyone in the wheelhouse stood in silent anticipation as the target began to increase in size, until Goodyear pointed and said, “There’s your ship.”

Optimism was high, but failure is always standing behind those who look for sunken ships. Despite the advances in equipment technology and computer projections, shipwreck-searching is not an exact science. The lesson of

Isis,

and at least two other wrecks that NUMA misidentified over twenty years, came back to haunt everyone. Several more passes were made over the remains of the ship far below. The dimensions checked out. So far, so good. Now it was the turn of the robotic vehicle and its cameras to probe the carcass.

While Goodyear’s first mate jockeyed

Ocean Venture’s

thrusters, fighting the current and waves to keep the ship stabilized above the wreck, the ROV was lowered over the stern. As the deck crane swung it over, the winch slowly played out the umbilical cord, sending the little unmanned craft into a sea turned gray from the dark, menacing clouds above. Inside the wheelhouse, Goodyear sat in front of a video monitor with a remote-control unit perched in his lap, moving the joysticks and switches that maneuvered the underwater vehicle’s motors and cameras.

Now every eye was locked on the monitor, waiting for the ROV to drop through the gloomy void to the bottom. After what seemed a millennium, we could see the drab, sunless silt spread across the sea bottom.

“I think we’re about fifty feet north of her,” said Davis.

“Turning south,” acknowledged Goodyear.

Plankton and sediment swirled like chaff in a windstorm, kicked up by a strong current. Visibility on the seafloor was poor, no more than six or seven feet. It was like looking through a lace curtain on a window as it swayed in the breeze.

Then a huge, dark shape began to loom in the murk before materializing into the hull of the ship. Unlike Isis, which had turned turtle on its descent, this wreck was sitting upright. She looked for all the world like a haunted castle or, better yet, the ominous house that belonged to Norman Bates and his mother in Psycho. Her black paint no longer showed, and her steel hull and remaining bulkheads had long been covered with marine incrustations and silt.

“Come around to the stem so we can count the prop blades,” said Davis.

“Heading toward the stern,” replied Goodyear, as he manipulated the ROV controls.

Large openings in the hull appeared, their steel borders disjointed and jagged, with debris spilling out from them.

“Could be where the torpedoes struck,” observed Fletcher.

Soon, a massive rudder and bronze propellers came into view.

“She’s got three blades,” Davis noted excitedly.

“The number of spindles holding the rudder look right,” added Goodyear.

“She’s got to be

Carpathia,”

Fletcher said, in growing excitement.

“What’s that lying in the sand off to the side of the hull?” Davis said, pointing.

Everyone stared intently at the monitor’s screen and the object half-buried in the silt.

“By God, a ship’s bell,” muttered Goodyear. “It’s

Carpathia’s

bell!”

He zoomed in with the ROV’s cameras, but the raised letters identifying the ship were too encrusted to read. The ravages of time and sea life had laid a blanket over them. Unable to make a positive identification from the bell or the bow proved irritating to the men in the wheelhouse.

The ROV rose from the bottom and moved along the dead hull, past rows of portholes, some still with glass in them, past the hatches through which

Tetanic’s

survivors had entered that cold dawn six years before

Carpathia

went down. The

Ocean Venture’s

crew could almost envision the slightly more than seven hundred people—pitifully few men, heartbroken wives, fatherless children—who had either climbed the ladders or been hoisted aboard

Carpathia’s

decks.

Dozens of trawl nets were entangled in the wreckage, making Goodyear’s job very tricky indeed. The upper superstructure and funnel were gone, collapsed into a great tangle of shattered wreckage. A huge conger eel came out of a jumbled mess to stare at the intruder to its domain. The ROV sailed over the forecastle, focusing on the deck winches, finding the fallen forward mast.

Suddenly, the cable became snagged, wedged in the twisted metal on the main deck.

It seemed as though, after eighty years in black solitude,

Carpathia

didn’t want to be left alone again. With a sensitive touch, Goodyear feathered the joysticks on the remote, retracing the ROV’s path until the umbilical cord finally pulled free. With a sigh of relief, he brought up the ROV and the first images of

Carpathia

since 1918.

With nothing more to be accomplished, the weary but exhilarated crew reluctantly stowed the ROV and the sonar and magnetometer gear and set a course back to Penzance, England. The disappointment over the

Isis

hung heavily on their minds. The big question was whether they had truly discovered

Carpathia,

or some other ship of the same design.

The absolute proof came in Halifax a few weeks later, when the renowned marine archaeologist James Delgado sat down and systematically compared the video images with the original blueprints of

Carpathia.

The rudder, the propellers, the sternpost, the position of the portholes all matched. Delgado made the final pronouncement.

“Carpathia

has been found!”

Thanks to the crew of the

Ocean Venture

and John Davis, the search is over. Here at last was the ship forever tied to that fateful day in April 1912. I can’t help but wonder who will be the next to see her bones. She has no treasure on board, certainly not in the usual sense. However, in the glass case in the purser’s office are the many medals, cups, plaques, and mementos commemorating her gallant role in rescuing the

Titanic

survivors. But I doubt they can be recovered, so deep are they within the collapsed superstructure.

Carpathia’s

trophies will probably rest with her forever.

She lies in five hundred feet of water about three miles from the original

Carpathia

coordinates and a hundred and twenty miles off Fastnet, Ireland. Somehow, it almost seems fitting that she joined the White Star liner in the depths of the cruel sea.

NUMA and ECO-NOVA are proud to have recaptured a celebrated piece of history.

Carpathia

left us all with an inspiring legend that will be cherished by all who love the sea and her rich history.

PART ELEVEN

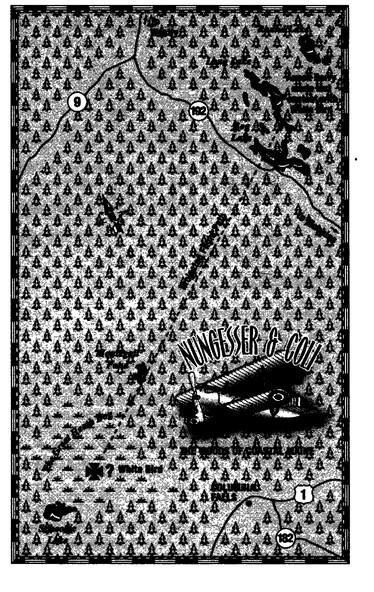

L’Oiseau Blanc

I

The White Bird 1927

“SEEMS LIKE IT’S A FIFTY-FIFTY PROPOSITION,” CHARLES Nungesser noted.

“And how do you figure that?” François Coli asked.

The men were standing on the packed dirt at La Bourget Airfield outside Paris. Nungesser was a handsome man with a rakish air. His chin sported a scar from one of his many crashes during World War I, but his eyes still burned with an intensity that showed no fear. Coli was more compact, with a jaded air about him. His upper lip was covered with a bushy black mustache. A black patch covered the eye he had lost in the Great War, and his cheeks were becoming jowls. Coli’s double chin was resting on a silk flight scarf.

“Either we take off in this fuel-laden beast,” Nungesser said, “or we crash.”

“Flip of the coin,” Coli said.

“Soar into greatness,” Nungesser said, “or burn into history.”

“You make it sound so fun,” Coli said wearily.

To attempt the risky Paris—to—New York flight, Nungesser and Coli were inspired by glory, not money. The money due the winner of the Orteig Prize had awaited a claimant since 1919. Raymond Orteig, owner of the fashionable Brevoort and Lafayette Hotels in Paris, offered $25,000 to the first airplane that completed a Paris—to—New York or New York—to—Paris nonstop flight. While $25,000 was not an inconsequential sum, the acclaim that would be garnered by the winners was priceless.

Whoever won the Orteig Prize would be the world’s most famous living person.

THE PRIOR YEAR, fellow Frenchman Rene Fonck, the leading Allied fighter pilot in World War I, made an attempt. The flight had ended in disaster. Fonck’s Sikorsky S-35 crashed on takeoff from Roosevelt Field in New York with a crew of four. Fonck and his copilot lived, but the radio operator and the mechanic aboard perished in the flames.

Commander Richard Byrd, famed for his exploration of the North Pole, assembled a crack team to make an attempt. A modified Fokker trimotor, similar to the plane Byrd had used for his North Pole journey, was selected. On April 16, Anthony Fokker, Byrd, pilot Floyd Bennett, and a radio man crashed while landing on a final test flight. No one was killed, but three of the four aboard were injured.

Ten days later, another group mounted an effort. With sponsorship from a U.S. group of war veterans named the American Legion, Lieutenant Commander Noel Davis bought a Key-stone Aircraft Corporation Pathfinder. When performing the final tests at Langley Field in Virginia, the Pathfinder went down, killing both Davis and his copilot, Stanton Wooster.

Next to tempt fate was Clarence Chamberlin in a Wright-Bellanca WB-2. Chamberlin and copilot Bert Acosta tested the plane, named

Columbia,

by staying aloft for a little over fifty-one hours, a new world’s record and more than enough time to reach Paris. On one of their last test flights, they lost their left wheel after takeoff. Chamberlin managed to land, but the damage to the plane would require time to fix.

AT THE SAME time, in San Diego, at the Ryan Aircraft Company, a former mail pilot named Charles Lindbergh was waiting for a low-pressure area to lift over the Rockies so he could fly east to make a solo attempt. He was sitting on a wooden folding chair in the hangar next to his plane,

Spirit of St. Louis,

studying the current weather reports, when the news reached him that Nungesser and Coli would soon take off from Paris.

The date was May 8, 1927.

“MONSIEUR,” THE MECHANIC said quietly, “the time is here.”

It was 3 A.M., the darkest part of night. Nungesser and Coli were lying on wooden pallets covered by thick horsehair mattresses in a comer of the hangar at La Bourget Airfield. Nungesser was clutching his favorite war medal; Coli had removed his eye patch. They awoke immediately. Nungesser reached for the steaming cup of Viennese coffee the mechanic offered, while Coli sat upright and stared at the plane that would carry them into the history books.

L’Oiseau Blanc

(

The White Bird)

was a French-built Levasseur PL-8. The white biplane had detachable wheels that would be jettisoned after takeoff and a watertight belly made of treated plywood that allowed it to land on water like a seaplane. Powered by a sophisticated water-cooled, twelve-cylinder Lorraine-Dietrich engine that produced 450 horsepower, spinning a massive propeller designed to fold away for landing, the plane had the smooth good looks of a dove in flight.

“She’s a beautiful mistress,” Coli said, as he pulled the eye patch over his socket.

“So much more so,” Nungesser said, “with the emblem attached.”

Coli simply smiled.

Nungesser’s ego was exceeded only by his flying ability. When he had insisted on attaching his personal emblem, Coli had readily agreed. The emblem was a black heart with drawings of twin candelabra holding lighted candles pointing toward the round humps at the top. Between the candles was a drawing of a casket with a cross on the top. Below that was the ancient skull-and-crossbones symbol. The emblem was positioned directly below and slightly to the rear of the open cockpit where Nungesser would fly the plane.

Coli rose from the mattress and pulled on his leather flight suit. “We should make ready,” he said. “The president will be here soon.”

“He’ll wait,” Nungesser said, as he leisurely sipped his coffee.

OUTSIDE THE HANGAR, the sky was dotted with millions of stars. A rare wind flowing east washed across the ground, and if they were lucky it would carry

White Bird across

the Atlantic. André Melain was not staring at the stars or worrying about the wind. Instead, he was carefully smoothing the packed-dirt, two-mile-long runway with a small diesel tractor that featured a crude spotlight hooked to the battery. Placing the tractor in neutral, he climbed from the seat, then lifted some twigs from the dirt. After placing them in a metal box at the rear of the tractor, he climbed back aboard and resumed his meticulous work.

THE PRESIDENT OF France, Gaston Doumergue, had heard the rumors that Chamberlin had taken off in the now-repaired

Columbia.

After waiting to receive word from the French ambassador in New York City that the report was erroneous, he set off for the airfield.

The Orteig Prize had been funded by a Frenchman, and it was a matter of national pride that it also be claimed by a French team of flyers. Right this instant, however, Doumergue was cursing French engineers. The 1925 Renault 40CV carrying the president was stopped on the side of the road three miles distant from La Bourget. The driver had the hood of the car, emblazoned with the diamond-shaped Renault emblem, raised and was staring into the engine compartment. He fiddled with some wires, then returned to his spot behind the wheel and turned the engine over.

The engine fired and settled into a quiet purr. “My apologies, Monsieur,” the driver mumbled, as he placed the Renault in gear and pulled away from the curb.

Just under ten minutes later, they arrived outside the hangar.

FRANÇOIS COLI WAS sipping from a glass of Merlot and nibbling on his breakfast of crusty bread smeared with runny Brie. Charles Nungesser had spurned the offer of wine for another cup of coffee rich with heavy cream and sugar. He was alternating between a chunk of bread heavy with pate and a hard-boiled egg in his left hand.

“Is the mailbag safely aboard?” he inquired of a mechanic who walked past.

“Stowed forward, as you requested,” the man noted.

Nungesser nodded. The special postcards would be post-marked after their arrival in New York and later sold as souvenirs for a handsome profit. He stared over at his navigator. Dressed in his full-leather flight suit, Coli looked like a sausage with a meaty head attached. Still, in spite of their differences, Nungesser trusted Coli’s ability completely. Coli came from a family of seafarers based in Marseilles, and navigation was in his genes. Shortly after the war, he had piloted the first nonstop flight from Paris to Casablanca across the Mediterranean. He was originally slated to make his own attempt for the Orteig Prize, but Coli’s plane had been destroyed in a crash.

For all his quiet demeanor, Coli wanted the honor as much as Nungesser.

THE RENAULT STEERED past the crowds and made its way to the side of the hangar. The driver shut off the engine and climbed out, stepped back to the rear door, and opened it for Doumergue. The French president walked to the hangar’s side door, waited for the driver to open that, too, then walked inside.

Glancing to the right, nearest the overhead doors, he saw the white Levasseur. The tail of the plane was painted with a vertical stripe of blue nearest the cockpit, then an open stripe of white, then a stripe of red at the end of the tail. The colors of the French flag. Horizontally, above the stabilizer, were black block letters that read: P. LEVASSEUR TYPE 8. Just below the stabilizer was a painted anchor. The sheet metal surrounding the engine was also white and was rounded, like the end of a bullet. The nose of the plane was peppered with access panels, four round air intakes per side and a single exhaust pipe to port and starboard.

The light from the few electric lights in the hangar was dim, but Doumergue could make out Nungesser and Coli standing off to one side. He walked over and shook the men’s hands.

“This is the first I’ve seen the plane up close,” Doumergue said.

“And what do you think, Monsieur President?” Nungesser asked.

“The cockpit is farther to the rear than I thought it would be,” Doumergue admitted.

“Three aluminum fuel tanks that can carry 886 gallons are mounted just under the wings, just aft of the engines,” Coli said, grinning. “We wouldn’t want to run short of fuel before reaching New York.”

“An excellent idea,” Doumergue said.

Nungesser looked over to the French president. “Have we heard word of Chamberlin?”

“The rumors were false,” Doumergue noted. “At last report, he was still in New York.”

“Then the winds are against him and favoring us,” Coli said.

“So it would seem,” Doumergue said.

Nungesser turned and shouted to a mechanic. “Hook White Bird to a tractor and pull her onto the runway. Monsieur Coli and I have a date in New York City.”

The dozen workers in the hangar broke into cheers.

THE EASTERN SKY was paling with the first light of the coming dawn, as Nungesser and Coli climbed into White Bird and started the engine. A cacophony of noises washed across the hundreds that had gathered to watch the historic journey. Popping noises sounded as the engine belched and wheezed and then settled into a loud roar. Puffs of smoke billowed from the exhaust ports.

Nungesser engaged the propeller for a test.

A loud thumping noise came as the massive wooden blades began to beat at the air. Next, a screech, as Nungesser powered up and moved

White Bird

a short distance.

“Manifold pressure and temperature okay,” Nungesser shouted to Coli.

“Check,” Coli said.

“Control surfaces responding—fuel shows full.”

“Check,” said Coli.

“I say it’s a go,” Nungesser said.

“Confirm the go,” Coli shouted. “Next stop, New York City.”

Nungesser steered

White Bird

into an arc at the far end of the runway, then stopped and ran up the engines while holding the brake. The crowd had followed the plane downfield, and hundreds of people stood watching. Nungesser raised his arm over his head and as far out of the cockpit as he could, then waved to the crowd.

“Au revoir,”

he shouted.

He pushed the throttles forward and started down the runway. It was 5:17 A.M.

ANDRÉ MELAIN WATCHED

White Bird

roll past, then followed with the tractor. From his perch atop the tractor, he had a better view than most of the crowd.

White Bird

was gaining speed and passed the one-mile marker. Slowly, the plane inched skyward, then sagged back onto the runway. A collective sigh ran through the crowd. A hundred yards farther and the tail wheel was far off the ground. Suddenly, Melain could see under the belly of

White Bird

as she climbed foot by foot from the runway. A mile past the end of the runway and the plane was only seventy feet in the air. Then he saw what he was watching for—Nungesser dropped the landing gear, which fell through the dim light to the ground below.

Melain set off in the tractor to retrieve the prize.

“COAST AHEAD,” NUNGESSER shouted.

Coli marked it on a chart. “You are right on course.”

White Bird

passed over the English Channel at 6:47 A.M.

NUNGESSER STARED AT the gauges. All seemed in order. He headed toward Ireland as he thought of his past. His had been a life of challenges and adventure. As a teenager, he had favored boxing, fencing, and swimming—all individual sports. As a young man, he’d found school oppressive and his desire to be outdoors almost overwhelming. At sixteen, he had quit school and convinced his parents to allow him to visit an uncle in Brazil. The uncle had resettled in Argentina, and it would be nearly five years before Nungesser found him, but in Brazil

Nungesser indulged in his love of mechanical things. He began to race motorcycles, and later automobiles, supporting himself with his increasing skills as a mechanic. He gambled, boxed for money, and lived the life of a bon vivant, but still something was lacking. He began to feel bored with his life and bound to the earth.

A few years later, he traveled to Argentina to locate his uncle. There he found the passion he had sought so long. Visiting an airfield one day, he approached a pilot who had just landed. He explained to the man that he was an accomplished automobile racer and thus felt qualified to fly—and the man laughed him off as if he were the village idiot. The man went inside, and Nungesser climbed into the cockpit, roared down the runway, and lifted off. After a short flight, he approached the runway and touched down. The owner of the plane was not so much angered as amazed.