Closing the Ring (68 page)

Authors: Winston S. Churchill

Tags: #Great Britain, #Western, #British, #Europe, #History, #Military, #Non-Fiction, #Political Science, #War, #World War II

* * * * *

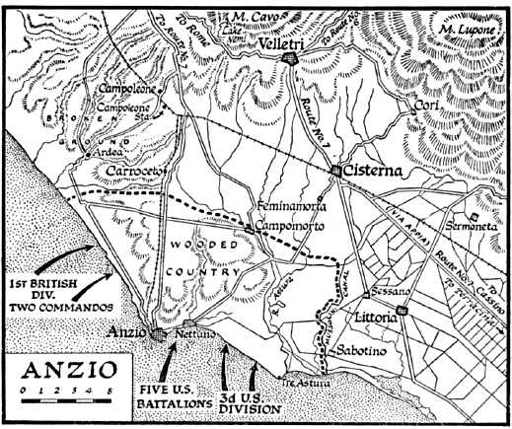

While the fighting at Cassino was at its zenith, on January 30, the VIth Corps at Anzio made its first attack in strength. Some ground was gained, but the 3d United States Division failed to take Cisterna and the 1st British Division, Campoleone. More than four divisions were already ashore in the beachhead. But the Germans, despite our air action against their communications, had reinforced quickly and strongly. Elements of eight divisions faced us in positions which they

had now had time to fortify. Galling artillery fire harassed the crowded lodgments we had gained and our shipping lying off the beaches suffered damage from air attacks by night. On February 2, Alexander again visited the battle-front, and sent me a full report. German resistance had increased, and was especially strong opposite the 3d United States Division at Cisterna and the 1st British Division at Campoleone. No further offensive was possible until these points were captured. The 3d Division had fought hard for Cisterna during the last two or three days. The men were tired and were still about a mile from the town. A brigade of the 1st Division was holding Campoleone railway station, but they were in a very long and narrow salient and were being shot at “by everything from three sides.” Alexander concluded: “We shall presently be in a position to carry out a properly co-ordinated thrust in full strength to achieve our object of cutting the enemy’s main line of supply, for which I have ordered plans to be prepared.”

Before effect could be given to Alexander’s orders, the enemy launched a counter-attack on February 3 which drove in the salient of the 1st British Division and was clearly only a prelude to harder things to come. In the words of General Wilson’s report, “the perimeter was sealed off and our forces therein are not capable of advancing.”

I had been much troubled at several features of the Anzio operation, as the following telegrams will show:

Prime Minister to General Wilson

(

Algiers

)

and C.-in-C. Mediterranean

6 Feb. 44

I do not want to worry General Alexander in the height of the battle, but I am not at all surprised at the inquiry from the United States Chiefs of Staff. There are three points on which you should touch. First, why was the 504th Regiment of paratroops not used at Anzio as proposed, and why is the existing British Parachute Brigade used as ordinary infantry in the line? Secondly, why was no attempt made to occupy the high ground and at least the towns of Velletri, Campoleone, and Cisterna twelve or twenty-four hours after the unopposed landing? Thirdly, the question asked by the United States Chiefs of Staff: Why has there been no heavily mounted aggressive offensive on the main front to coincide with the withdrawal of troops by the Germans to face the landing?

2. In my early telegrams to General Alexander, I raised all these points in a suggestive form, and particularly deprecated a continuance of the multiplicity of small attacks in battalion, company, and even platoon strength. I repeat however that I do not wish General Alexander’s attention to be diverted from the battle, which is at its height, in order to answer questions or write explanations about the past.

General Wilson replied that the 504th Paratroop Regiment was seaborne and not airborne because of a last-minute decision by General Clark. The British paratroops were employed in the line because of infantry shortage. On my second question he said there was no lack of urging from above, and that both Alexander and Clark went to the beachhead during the first forty-eight hours to hasten the offensive. Though General Lucas had achieved surprise, he had failed to take advantage

of it. This was due to his “Salerno complex”—that as a prelude to success the first task was to repel the inevitable enemy counter-attack. He did not feel sure of this before the arrival of the 1st United States Armoured Division combat team. The assault, said Wilson, was only geared to function at a slow speed. He also explained the difficulties of forcing the main front on the Rapido River and around Cassino.

General Marshall shared my concern, and I passed this report to Washington with the following comment:

Prime Minister to Field-Marshal Dill

(

Washington

) 8 Feb. 44

You should impart this report to General Marshall at your discretion.

… My comment is that senior commanders should not “urge,” but “order.”

All this has been a disappointment to me. Nevertheless, it is a great advantage that the enemy should come in strength and fight in South Italy, thus being drawn far from other battlefields. Moreover, we have a great need to keep continually engaging them, and even a battle of attrition is better than standing by and watching the Russians fight. We should also learn a good many lessons about how not to do it which will be valuable in “Overlord.”

* * * * *

The Admiral had been even better than his word about the handing-craft. I now put a direct question to him:

Prime Minister to Commander-in-Chief Mediterranean

8 Feb. 44

Let me know the number of vehicles landed at Anzio by the seventh and fourteenth days respectively. I should be glad, if it were possible without too much trouble or delay, to distinguish trucks, cannon, and tanks.

The reply was both prompt and startling. By the seventh day, 12,350 vehicles had been landed, including 356 tanks; by the fourteenth day, 21,940 vehicles, including 380 tanks. This represented a total of 315 L.S.T. shipments. It was interesting to notice that, apart from 4000 trucks which went to and fro

in the ships nearly 18,000 vehicles were landed in the Anzio beachhead by the fourteenth day in order to serve a total force of 70,000 men, including of course the drivers and those who did the repair and maintenance of the vehicles.

I replied on February 10:

Prime Minister to Commander-in-Chief Mediterranean

10 Feb. 44

Thank you for information.

How many of our men are driving or looking after eighteen thousand vehicles in this narrow space? We must have a great superiority of chauffeurs. I am shocked that the enemy have more infantry than we. Let me have our latest ration strength in the bridgehead.

Later the same day, further reports came in. General Wilson said that the weather had spoilt our air attacks. The 1st British Division was under severe pressure and had had to give ground and Alexander was arranging to relieve it.

All this was a great disappointment at home and in the United States. I did not of course know what orders had been given to General Lucas, but it is a root principle to push out and join issue with the enemy, and it would seem that his judgment was against it from the beginning. As I said at the time, I had hoped that we were hurling a wildcat onto the shore, but all we had got was a stranded whale. The spectacle of eighteen thousand vehicles accumulated ashore by the fourteenth day for only seventy thousand men, or less than four men to a vehicle, including drivers and attendants, though they did not move more than twelve or fourteen miles, was astonishing. We were apparently still stronger than the Germans in fighting power. The ease with which they moved their pieces about on the board and the rapidity with which they adjusted the perilous gaps they had to make on their southern front was most impressive. It all seemed to give us very adverse data for “Overlord.”

I cabled to Alexander:

Prime Minister to General Alexander

10 Feb. 44

… I have a feeling that you may have hesitated to assert your

authority because you were dealing so largely with Americans and therefore

urged

an advance instead of

ordering

it. You are however quite entitled to give them orders, and I have it from the highest American authorities that it is their wish that their troops should receive direct orders. They say their Army has been framed more on Prussian lines than on the more smooth British lines, and that American commanders expect to receive positive orders, which they will immediately obey. Do not hesitate therefore to give orders just as you would to our own men. The Americans are very good to work with, and quite prepared to take the rough with the smooth.

Alexander replied on February 11:

General Alexander to Prime Minister

11 Feb. 44

The first phase of operations, which started so full of promise, has now just passed, owing to the enemy’s ability to concentrate so quickly sufficient force to stabilise what was to him a very serious situation. The battle has now reached the second phase, in which we must now at all costs crush his counter-attacks, and then, with our own forces regrouped, resume offensive to break inland and get astride his communications leading from Rome to the south. This I have every intention of doing. Out of the thirty-five battalions of the VIth Corps casualties are as follows: British, up to February 6—killed, 285; wounded, 1371; missing. 1048. American, up to February 9—killed, 597; wounded, 2506; missing, 1116. These losses include those of nine Ranger battalions. Total casualties, 6923. I am very grateful for your kind message at the end of your telegram. I well realise the disappointment to you and all at home. I have every hope and intention of reaching the goal we set out to gain.

* * * * *

The expected major effort to drive us back into the sea at Anzio opened on February 16, when the enemy employed over four divisions, supported by four hundred and fifty guns, in a direct thrust southward from Campoleone. Hitler’s special order of the day was read out to the troops before the attack. He demanded that our beachhead “abscess” be eliminated in

three days. The attack fell at an awkward moment, as the 45th United States and 56th British Divisions, transferred from the Cassino front, were just relieving our gallant 1st Division, who soon found themselves in full action again. A deep, dangerous wedge was driven into our line, which was forced back here to the original beachhead. The artillery fire, which had embarrassed all the occupants of the beachhead since they landed, reached a new intensity. All hung in the balance. No further retreat was possible. Even a short advance would have given the enemy the power to use not merely their long-range guns in harassing fire upon the landing-stages and shipping, but to put down a proper field artillery barrage upon all intakes or departures. I had no illusions about the issue. It was life or death.

But fortune, hitherto baffling, rewarded the desperate valour of the British and American armies. Before Hitler’s stipulated three days, the German attack was stopped. Then their own salient was counter-attacked in flank and cut out under fire from all our artillery and bombardment by every aircraft we could fly. The fighting was intense, losses on both sides were heavy, but the deadly battle was won.

One more attempt was made by Hitler—for he was the will-power at work—at the end of February. The 3d United States Division, on the eastern flank, was attacked by three German divisions. These were weakened and shaken by their previous failure. The Americans held stubbornly and the attack was broken in a day, when the Germans had suffered more than twenty-five hundred casualties. On March 1, Kesselring accepted his failure. He had frustrated the Anzio expedition. He could not destroy it. I cabled to the President:

Prime Minister to President Roosevelt

1 Mar. 44

I must send you my warmest congratulations on the grand fighting of your troops, particularly the United States 3rd Division in the Anzio beachhead. I am always deeply moved to think of our men fighting side by side in so many fierce battles and of the inspiring additions to our history which these famous episodes will make. Of course I have been very anxious about the beach-head, where we have so little ground to give. The stakes are very

high on both sides now, and the suspense is long-drawn. I feel sure we shall win both here and at Cassino.

* * * * *

On February 22, 1944, I gave a general account of the war to the House of Commons. In this setting Anzio was presented in its proportion. I told the story as far as was then possible.

It was certainly no light matter to launch this considerable army upon the seas—forty thousand or fifty thousand men in the first instance—with all the uncertainty of winter weather and all the unknowable strength of enemy fortifications. The operation itself was a model of combined work. The landing was virtually unopposed. Subsequent events did not however take the course which had been hoped or planned. In the upshot we got a great army ashore, equipped with masses of artillery, tanks, and very many thousands of vehicles, and our troops moving inland came into contact with the enemy.

The German reactions to this descent have been remarkable. Hitler has apparently resolved to defend Rome with the same obstinacy which he showed at Stalingrad, in Tunisia, and, recently, in the Dnieper Bend. No fewer than seven extra German divisions were brought rapidly down from France, Northern Italy, and Yugoslavia, and a determined attempt has been made to destroy the bridgehead and drive us into the sea. Battles of prolonged and intense fierceness and fury have been fought. At the same time the American and British Fifth Army to the southward is pressing forward with all its strength. Another battle is raging there.